Who has heard of Gustave Caillebotte? Among my family members who grew up in the Chicago area, his most famous painting — Paris Street; Rainy Day — is widely beloved. This is solely due to its prominent placement in the Art Institute of Chicago, where it marks the entrance of the Impressionist wing. My family has many memories of walking up the white marble stairs to see it atop in all its enormity: seven feet high and nine feet wide. But that’s all they knew about Caillebotte — and that was more than I could say. I, who grew up in the distant lands of Madison, Wisconsin, had no special childhood memories of this painting. When I was invited to visit the special Caillebotte exhibition with my family, I said yes, but only as an excuse to take a weekend excursion during the dog days of summer. I tried to tell my husband why I was going away for the weekend, but I couldn’t even keep the man’s name straight in my head. I read it but it disappeared immediately, as if it had been whispered on the phone in a loud bar. What was that? Caillebotte. I can’t hear you! Caillebotte. I’ll have to call you back later!

Even though you probably haven’t heard of Caillebotte, he might be the key to artistic creativity in the age of AI. Or if not Caillebotte himself, then the idea of Caillebotte — the Caillebotteness in us all. But first, a little background.

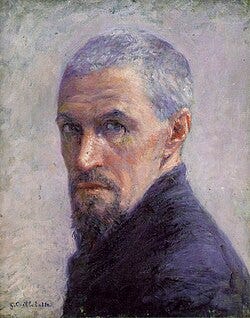

In his day, at least, Caillebotte was well known. His biggest long-lasting contribution to the Impressionist art scene was as a convener and patron. But his own works were also acclaimed during his lifetime. He played with perspective and elevated new subjects while slowly incorporating and eventually being subsumed by the Impressionist style. His success was a direct result of meeting the Impressionists after his first masterpiece was rejected by the Paris Salon.

Back in the mid-1800s, if you wanted to make it as an artist in France, you had to present at the official yearly art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, known as the Salon de Paris, or Paris Salon for us rubes. The academy was rigid about the type of work it would accept. Historical and mythological subjects were encouraged — Greek myth was favored — with a reverence for tradition and a simple, structured society. If an artist wanted to paint someone from the lower classes, only a peasant or farmer would do. The style had to be realist, classical, in the European tradition; experimentation was discouraged. The rules became more restrictive as time went on, so that even famous artists already featured at the Salon found their new works rejected.

Eventually, many artists got weary of the rules and rejections and complained until Emperor Napoleon III decided to host the Salon des Refusés, or “exhibition of rejects,” in 1863. Ten years later, after Napoleon III was deposed (more on that later), the new French Republic hosted another, smaller Salon des Refusés, but no one was happy about that. It was widely mocked, and the state was still selecting the “rejects” anyway, so artists had no say. Fed up, one man suggested they form their own society with their own exhibition. His name was Claude Monet. In 1874, Monet, alongside Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and others — the future powerhouses of the Impressionist movement — put on what would become known as the First Impressionist Exhibition.

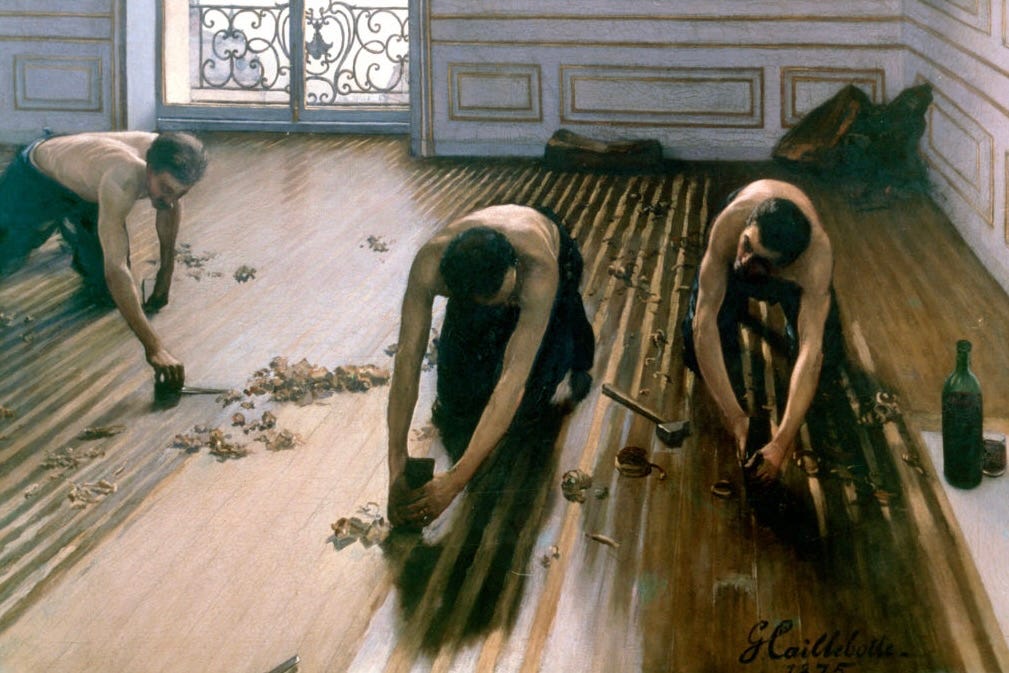

Caillebotte, meanwhile, was new to the painting scene and flush with cash following the death of his father. So he gave up art school and financed his own work. He must have attended this exhibition because he quickly became involved with the group — funding their work, paying for their studios, and eventually helping mount the second exhibition, where eight of his own works were first presented and acclaimed. (The most famous was The Floor Scrapers, a composition of shirtless men scraping paint off a floor, previously rejected by the Salon for being too vulgar.) He was bumped up to manager for the third exhibition, selecting artists and their works, before deciding the social politics were too annoying, so he went back to being a simple financial maven funding whomever he liked whenever he liked.

Although a little late to the party, Caillebotte quickly became one of the fathers of the movement. And yet, his most famous paintings don’t fall too deeply into the Impressionist style. His subjects were his style, and these subjects — shirtless men, boating men, suited men, city views — were rejected by the establishment, but the Impressionists took in the rejects, so he fell in with them. Fell in love with them, maybe, in a creative-soul sense, but possibly in a physical sense, too (many conjectured he was homosexual). Reading about their history, you feel a great deal of love between the artists, even the ones who disagreed with one another. They were inspired by each other and created something together. This creation stemmed from a reaction to what was happening in their world.

And what exactly was happening in the world? Modernization and nationalism — two sweeping forces that required and reinforced one another. Trains and telegraphs allowed for capital cities to connect with far-flung places. Nationalist projects often pushed for yet more modernization and connection. In France, train loads quadrupled between 1845 and 1850 and, under Napoleon III’s oversight, increased eightfold between 1850 and 1860. Napoleon III oversaw massive expansion of the sewer system, gas lights, parks, train stations, public buildings, heavy industry, photography, and more. Medieval alleyways were demolished to build new, large open boulevards. Then in 1870, Napoleon was deposed, giving way to the formation of the Third French Republic, which some argue marks the “real” beginning of France as a nation and the idea of the “Frenchman.” Meanwhile, in 1871, both Germany and Italy unified. The world was changing not only on a physical plane but on an emotional one, too. Everything was in flux: the composition of a neighborhood, a city, a country — where you were from, how you identified, who you were.

Impressionism is, in a sense, defined by negation: a rejection of modernization, focusing instead on daily life and country scenes. A rejection of visual accuracy, favoring quick brush strokes that capture a feeling instead. A rejection of the idea of toil; rather than sit in a studio for hours and days, many painted en plein air — completing a painting in its entirety outdoors. Impressionism is easy to love. Maybe too easy. By that I mean it is easy for people who don’t know anything about art to like Impressionist art. The colors are pleasing and the point is clear. Look at 10 different versions of the same haystack and you can see how the world changes even while the haystack stays the same. Individual moments are fleeting; everything is a perception. The world changes daily, and the viewer changes even more frequently, so each moment is something worth capturing. You can see the artist’s mind, looking at a flower, looking at a pond, looking at the sky, and refracting it just so. It makes you see the flower, the pond, the sky itself differently, with the understanding that it is all simply an impression. And there is no need to read a painting plaque to achieve this understanding. Still, at the time, it was groundbreaking, even rebellious, to paint in this manner.

Caillebotte, I have to say, did nothing groundbreaking on the Impressionist front. A plaque at the Art Institute of Chicago’s special exhibit proudly states that Boulevard Seen From Above is his most experimental work.

Why was this so groundbreaking? Because Caillebotte used “the high angle of his balcony to portray almost abstracted snapshots of the daily life below.” He often painted people on balconies or people looking out from balconies. Had no one considered painting from a balcony before? I’m not sure, but if not, kudos to Caillebotte. Still, I have to imagine someone else would have thought of it eventually.

Rather, Caillebotte’s contributions to the art scene were those of subject, not style. Take The Floor Scrapers, for instance. Yes, there is some interesting glow to the wet floor, clearly inspired by Impressionism’s focus on water and light. But the emphasis is on the men themselves. Here are men of the underclass — not idealized peasants, but heroic nonetheless, flexible and strong. This painting, however, was criticized by some for not being Impressionistic enough. Émile Zola, for instance, called it a “painting that is so accurate that it makes it bourgeois.”

Here is Caillebotte’s most famous painting, the aforementioned Paris Street; Rainy Day. Once again, the ground glows from the dampness. Aside from that, where is the Impressionism? Is there any? The perspective is interesting, and the scene is new, society-wise: life on a wide-open boulevard. But I don’t see a single raindrop. It seems it isn’t even raining anymore, yet everyone is holding their umbrellas.

Caillebotte also painted trains. What better subject to showcase at this time? What was more ripe for exploration? What better way to encapsulate the feeling of the world rushing towards you, powerful and unstoppable?

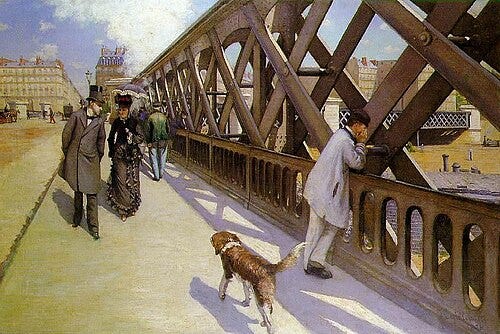

And yet, the most prominent of his train paintings was Le Pont de l’Europe, presented in the Third Impressionist Exhibit in 1876.

You cannot see a train in this painting. Only its smoke. And no one around is paying much attention to that. A stray dog passes by while a couple walks awkwardly three steps away from each other. Some have speculated that the woman is a prostitute; others that the man is gayly ignoring his wife to admire the nearby man’s posterior. This other man looks over the bridge, presumably at the trains passing by. So what is the painting trying to say? People of different classes are in the same space for possibly the first time and they are existing near a train. Okay? Is blandness the point? It is far less romantic than the other Impressionist bridge paintings of that era. Is it meant to be looked at with disgust?

Across the room in the exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago, however, was another, Sur le Pont de L’Europe. This painting made me gasp:

It has perspective and a story. The subject is clearly the train behind the bridge. This is what the figures are staring at and where the eye is drawn. We still can’t see it, but we can try to peek through the bars to find it in the smog. And we have a feeling: blue. All is blue. The sky is blue, the bridge is blue, the suits are blue. Apparently, Caillebotte did not exhibit this one because that same year Monet was exhibiting a painting series of that same train station as seen from below.

This is one of a set of 12 paintings Monet released simultaneously, all of the same train station, with different angles and moods. I wonder who influenced whom. Caillebotte’s first train painting, the bland one above, came out the year prior. We know Monet painted quickly in those years. I would guess Caillebotte influenced Monet and then stepped aside, because Monet’s work was far more Impressionist and made more sense to display in an Impressionist exhibition.

But I prefer Caillebotte’s train paintings to Monet’s. Even the bland one. There are people and a story, and the painting Sur le Pont de L’Europe in particular feels like a key to Impressionism as a whole. Everyone was trying to understand what was happening, and many were simply paralyzed — watching, frozen in frame — while others turned away. Seeing these paintings in person made my whole trip worth it. I wanted to feel that change. That moment when the world rushes towards you, and though you can hardly see it, and though you can’t do a thing, you can feel it.

A moment much like the one we’re in right now.

The world is always changing. Sometimes it changes more quickly than before, like during the nationalism and industrialization of the 1800s. Every day brings new stories about how technology is changing society for better or worse. Nobody knows how AI will upend the world. We do know that the world’s most powerful people expect unprecedented change. Artificial intelligence is here, they say. Or if it’s not, something like it is. They are betting billions of dollars on its success. Journalists are hosting interviews with AI recreations of dead children to push political messages, publishing AI-generated lists of fake books you should read, and eulogizing their own jobs. What will happen to our identities? To fiction, to art? A train is rushing towards us, and we can’t even see it; we can only catch a glimpse of the smoke.

When photography became common, visual artists responded in two ways. Some embraced it, using photographs to capture images and reproduce them later. Others, like the Impressionists, felt unshackled from the restraints of realism. The rejection of photography didn’t lead to artists everywhere putting down their paintbrushes. They didn’t go back to cave painting either. They moved diagonally to the way the world was moving and created something fascinating. Even if you don’t find Impressionism interesting, it opened the door for the wilder and weirder: the Post-Impressionism of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, which later inspired the Cubism of Picasso et al, or, in a different direction, the Fauvism of Henri Matisse, which inspired the German expressionists . . .

Do we have an art era anymore? Through internet-driven globalization, there has been a great melding of the world. Labubus on every continent. The proliferation of large language models may increase this trend, a melding of the whole internet into one friendly chatbot. Everything seems to grow more predictable. This makes it harder for any individual voice to stand out before being subsumed into the writhing mass of the internet. We have a new Paris Salon in town, and its name is ChatGPT. It’s inevitable, everyone says. It’s our ruler; take a bow.

But maybe not.

Caillebotte’s paintings still don’t mean much to me, except in the way they brought me together with my family and allowed me to understand them a little more. I can now visualize the ritual they grew up with — that long walk up the marble steps, the apex of a giant Parisian rainy day. I can understand the tradition of returning to the same painting over and over, and how the painting doesn’t change, but the world does, so that each time is different, like Monet’s many haystacks. Impressionism is all about subjectivity — the scene is how you feel about it, not how it really is — and subjectivity is fleeting and impossible to explain. A painting has power when it allows individuals to form their own relationships to it. Or lack thereof. Maybe someone doesn’t resonate with a painting, but they form a relationship to something else instead, like a book or a song, something that makes them feel more human.

Caillebotte may not have changed the world with his paintings, but he changed the world with his relationships. If we’re on the cusp of being surrounded by virtual facsimiles, we must protect our human relationships even more. My family will never meet Caillebotte, and yet they love him all the same. I spent an afternoon in his world, where it felt like all his paintings were glad to see one another, a reunion of old friends.

I don’t expect readers of this essay to fall in love with Caillebotte or to visit this exhibit, which will soon close. I do hope we can find each other and deepen our connections with each other, and with the scenes we came from and the new ones we’re forming. Even if they’re small. Even if they’re digital. This is one way to face what’s coming, as artists, as human beings. The Impressionists couldn’t stop societal change from happening, but they could adjust how they responded to change and help others respond, too. They created a psychic distance from the future and immortalized the fleeting now. They are long gone yet millions of people still line up to view their paintings. Through these dead painters’ eyes, we can stand on a bridge and look for the train in the distance. We can’t see it coming, but we need to keep looking.

Denise S. Robbins is the author of The Unmapping, a speculative climate fiction novel published in June 2025. Her stories and interviews have been published in The Barcelona Review, Gulf Coast, Chicago Review of Books, and many more. Find her on Substack at denisesrobbins.substack.com.

I enjoyed this very much. Your writing is wonderful and you handle the topic with grace. I also agree with the question of relationships vis-a-vis art and AI. I am a fiction writer, and I often wonder whether anyone will read books written by humans in ten years. But I think you touch on something really important, which is that, although most people don't think about it, they are connnecting with the artist through the work. It's not just the work. I think that's what you're saying?

Do you think I'm right? Do you think there's hope for books by humans?

Nice essay. I like how you link his work with social change and the historical context of the time. Also, as a longstanding member of the Art Institute, I've seen the famous painting more times than I can count, but none of his other work.

(Minor error: Italy was unified in 1861, not 1871.)