Alien Nation

On Gabriel McKee's 'The Saucerian: UFOs, Men in Black, and the Unbelievable Life of Gray Barker'

The calls came in around 10:40 on the night of August 25, 1955. Thomas McGuinn, the dispatcher on shift in the Hamilton County Sheriff’s office, had been on the job for three years, but had never encountered anything like this. Sgt. Ralph Weber and patrolman Ernest Nehrer were watching a “big, bright, round” object above the Fernald atomic plant — where uranium ore was processed for nuclear weapons.

Both Navy veterans (Weber had been an airman), the officers were in separate cruisers, watching the object from different locations as it hovered at 5,000 feet. McGuinn also fielded frantic calls from farmers in the area about the “bright, round and tannish in color” object. Nobody could identify the object, but its arrival was less than surprising.

For the past few days, the Cincinnati area had been besieged by unusual sightings. Members of the Ground Observer Corps, a civil defense group with eyes peeled toward the sky, reported airborne lights of several colors. According to contemporary researcher Leonard Stringfield, the lights were variously described as “blinking with a bobbing motion” and “hovering in pendulum-like motions.” Once they were caught on radar, the military responded swiftly: jets were scrambled from the Lockbourne Air Force Base to intercept the objects.

Stringfield, who stood in nearby Madison Place with binoculars pointed toward the sky, struggled to see the drama through heavy clouds, but recalled that “the continuous din of low flying jets gave the writer a familiar choking chill, one that he had known during the Pacific campaigns while waiting for the inevitable attack.” America, it seemed, was under invasion.

Others were less convinced.

During the flap of sightings, Conquest of Space was showing at the local Woodlawn Drive-In. The film about an international mission to Mars was standard sci-fi fodder of its day, but includes some interesting elements. The commanding officer, Col. Samuel Merritt, comes to believe the crew is acting against God’s will. After an astronaut dies on board, Merritt recites Psalm 38:3 before sending the corpse into space.

While viewers watched the space drama at the outdoor theater, “flickering red, green, and white lights” flew overhead. Afterward the theater’s owner, Nat Kaplan, wrote to the Motion Picture Exhibitor trade magazine with a theory that dismissed not only the local event, but the growing sightings across the country. Kaplan “pointed out that outdoor movie screens are built to reflect light skyward and that light bounces from screens.”

A response to Kaplan’s theory came from a reader in Clarksburg, West Virginia named Gray Barker, who operated the state’s “largest film buying-booking agency” and also happened to be the editor of The Saucerian, the “world’s largest publication about ‘Flying Saucers.’” Barker penned an eleven-paragraph screed, which the editors coyly trimmed down to three, so as to stress Barker’s firm dismissal: “we were always under the impression that drive-in screens, if tilted, were tilted DOWNWARD, to reflect the maximum light toward the audience. Perhaps his screen is remarkably different than most.”

Barker ended his letter with a gentle curse: “let me again protest Mr. Kaplan’s disservice to ‘saucer’ investigations—may his film rental rise!”

A 1956 episode of Wonderama, a Sunday morning children’s show, featured two puppets — Egbert the Bookworm and the Steam Shovel— and a man in a space suit. That man was 31-year-old Gray Barker, whose newly released book, They Knew Too Much about Flying Saucers, alleged that the government and Men in Black were silencing people who reported UFOs. An interesting choice for a kids’ show, but book publicity tours are rarely glamorous.

Some people’s names are their destinies. Barker was a carnival barker for the paranormal. A shrewd writer who realized that UFO believers and seekers were similar to fans, Barker stretched the truth until it snapped—exaggerating kernels of fact and perpetrating outright hoaxes. Barker ran a press, Saucerian Books, that published works on the fringe of the fringe: stories of contactees and mothmen and space lovers.

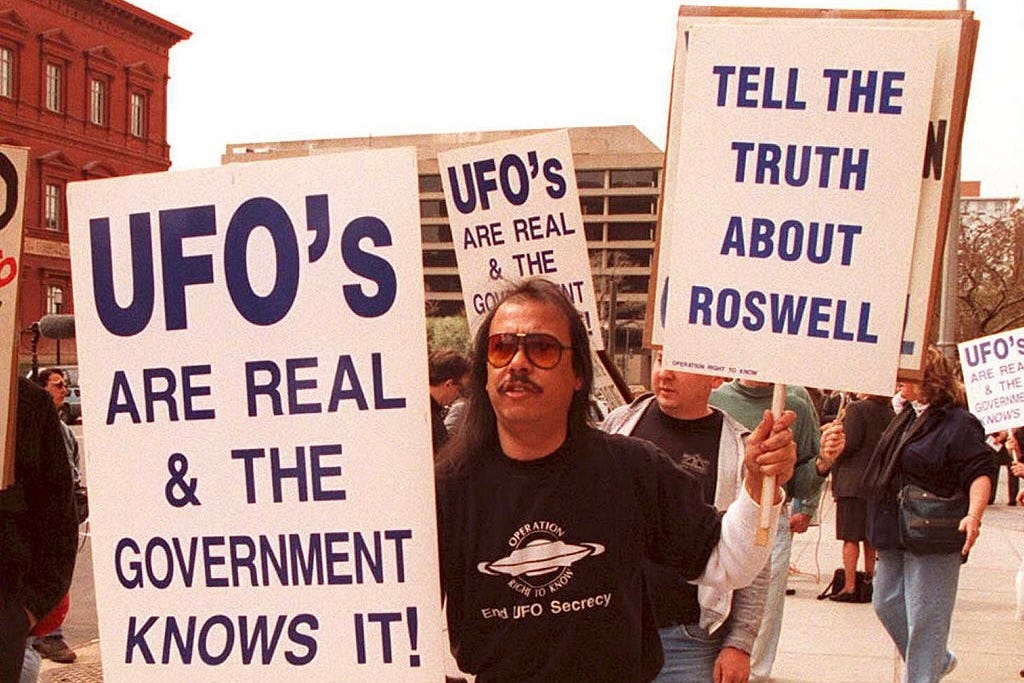

Far from a literary footnote, Barker is actually the perfect encapsulation of UFO culture in America: a community somewhere between a fandom and a religion, shepherded by hucksters who peddle schlock. For those who live and die by UFOs, it is in their best interest that the objects live up to their names: unidentified, a perpetual mystery that creates attention and generates (often very little) money.

The Saucerian: UFOs, Men in Black, and the Unbelievable Life of Gray Barker by Gabriel McKee from the MIT Press arrives at the perfect time. Fresh off months of frenzied sightings of mysterious drones in the Northeast, and with the release of alleged Navy encounters in recent memory, UFOs are a part of the public psyche again.

Media coverage of these new flaps, including in legacy publications like the Wall Street Journal, has been poor. Breathless revelations that the government used UFO sightings as disinformation campaigns to hide secret weapons programs ignore decades of reporting and released documents. Longtime investigator Jerome Clark has bemoaned the lack of historical knowledge of those covering the subject. I agree with Clark, and confess feeling like a kindred spirit with Barker when he critiqued the overzealous theater owner.

I’ve been researching and writing about UFOs for more than 20 years, starting with a local case from July 9, 1947. The day before, the Roswell Army Air Field had issued their infamous press release: “The many rumors regarding the flying disc became a reality yesterday when the intelligence office of the 509th Bomb group of the Eighth Air Force, Roswell Army Air Field, was fortunate enough to gain possession of a disc through the cooperation of one of the local ranchers and the sheriff’s office of Chaves County.”

On the other side of the country, in Morristown, New Jersey, a pilot named John H. Janssen observed four discs overhead. Janssen, who wrote an occasional airport column for local newspapers, took a photo — one of the first-ever published UFO images. The case was my introduction to the complexity of ufology. Although the image is striking, and Janssen initially appeared to be a credible witness, researcher Ted Bloecher notes that Janssen was prone to conjecture. “I really believe these craft to be operated by an intelligence far beyond that developed by we earth-bound mortals,” Janssen said, and thought “these are reconnaissance craft” that “are probably making a thorough study of us and our terrain and atmosphere before making any overtures.” Janssen soon claimed another, more dramatic encounter: “his plane was stopped in mid-air for a number of minutes while being scrutinized by a pair of discs hovering nearby.”

I knew to be suspicious of such observers. While in high school, I interviewed a former member of the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena, once the leading UFO research organization in America. As a scientist, he was both interested in and skeptical of UFOs — an important mixture. If I wanted to get truly serious about research, he told me, I needed to study Egyptology, ancient languages, folklore, and theology. I had to recognize that even if a field was new to me, I had to contend with its history. Most importantly, he said, be wary of single-witness cases. Most people couldn’t be counted on to tell the truth in small matters, let alone ones as tenuous as the paranormal.

It was an intimidating and necessary conversation to have, and prepared me for investigative work in other subjects, ranging from exorcisms to international hacking cases. Yet skepticism should fuel, but never neuter, a sense of wonder.

Early in The Saucerian, McKee writes that we should envision his book as a form of biography, but adds a disclaimer: “I encourage readers to keep in mind the primary focus of the work at hand — exploring Barker’s role in and impact on the production, distribution, and consumption of the stigmatized knowledge associated with UFOs and the paranormal — and forgive the relatively short shrift that other areas of his life may receive in what follows.”

That’s certainly a fine angle for a university press book. But McKee makes another statement that gives me pause: “To understand how the UFO macronarrative has grown and influenced our culture, we should first examine the only physical evidence that we have of UFO experiences: the books that describe, contextualize, and speculate about those experiences.”

McKee is not a ufologist; he’s an accomplished research librarian who works at NYU’s Library of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. Research librarians are gifted detectives. He discovered that Barker’s book They Knew Too Much about Flying Saucers appeared in the 1958 film Bell, Book and Candle. The movie depicts “a publisher of occult books (Jimmy Stewart) who becomes romantically involved with a practitioner of black magic (Kim Novak),” and Stewart’s shelves are lined with multiple copies of Barker’s book. McKee concludes: “Despite the similarities between the topics published by Stewart’s character” and Barker, “it’s most likely that the shelves were stocked from remaindered titles acquired by the film’s set dressers. This would indicate that by the beginning of filming in 1958, Barker’s book had run its course, at least as far as the mainstream book trade was concerned.” I can’t help but applaud that level of observation.

Despite these talents, McKee’s dismissal of UFO evidence undercuts the complexity of his subject. McKee desires literary and linguistic approaches to UFOs. He is correct that the “unidentified nature of an unidentified flying object means that, tautologically, the percipient doesn’t know what they saw,” and that Barker “simultaneously strove to preserve the mystery surrounding this ungraspable subject and to package and commodify it for an audience that he cultivated and nurtured.” He also reminds readers that modern American UFO discourse is inextricable from language by citing Kenneth Arnold’s description of his seminal sighting in June 1947: “Arnold compared their shape to that of a pie plate, but newspapers picked up a different term for their headlines, from Arnold’s comment that they moved ‘like a saucer would if you skipped it across the water.’” Flying saucers was a description of movement, not shape.

Yet McKee’s narrative method is too convenient for his material. UFOs are more than a literary medium. One of the most compelling American cases — a 1964 sighting of a craft and humanoids by Socorro, New Mexico policeman Lonnie Zamora, with trace evidence and corroboration — merits a single sentence in the book.

This is the conundrum of The Saucerian: it’s a great book on Barker the man (and showman), but it misses the opportunity to be a great book about UFOs. Perhaps I am being too greedy here, and again, channeling a bit of Barker’s own frustration about the subject.

Let me say what McKee does well. Barker and UFOs are preternaturally American: kooky and mystical. Although Barker was skeptical of the paranormal, he believed in belief, so to speak: he was a populist, a poet, a closeted gay man in West Virginia in the mid 20th century. His central role in the burgeoning UFO movement meant that many of the essential tropes of UFOs that last to the present can be traced back to his pen and imagination.

Barker “mythologized” when Men in Black visited Albert Bender, a fellow ufologist. The ending to They Knew Too Much about Flying Saucers remains both chilling and clever:

I am not alarmed about bug-eyed monsters, little green men, or dero who may or may not be shooting at us with rays from far underground.

Something else disturbs me far more.

There exist forces or agencies which would prevent us from finding out whether or not there are such green men, or bug-eyed monsters, or saucers with things in them.

I have a feeling that some day there will come a slow knocking at my own door. They will be at your door, too, unless we all get wise and find out who the three men really are.

Barker corresponded with everyone — researchers, believers, and skeptics alike — and his playful nature belied a serious core. “I AM thoroughly dedicated to promoting UFO crackpottery,” Barker wrote in a letter. Fellow UFO trickster James Moseley said that he and Barker’s main contributions were “to stir the ufological pot when things got dull.” Like a good satirist, though, Barker respected his subject, and his audience.

McKee’s conclusion in The Saucerian is sound: Gray Barker’s “influence is enormous, albeit scarcely untraceable, affecting the rhetoric of UFO literature more than its substance.”

Nick Ripatrazone is the Culture Editor for Image Journal, and a Contributing Editor for the Catholic Herald of London. He has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, GQ, and The Atlantic, and his most recent book is The Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century America.

My father always claimed that he saw a UFO flying over our reservation in the 70s. And I'd tease him and say, "Damn, even the alien anthropologists are obsessed with us Indians."

Thank you for this review. My interest dates back to a late 1960s flap in Newfield, NY. We spent a lot of time at night on hills watching, or tramping around in search of circles. Folks from the surrounding area would gather at our house once a month and share their stories. My first hearing of the Men in Black, then reported as a local phenomena. Decades later I held up filming of Men in Black II as I was working for the MTA on the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel ventilation building--the MiB headquarters in the film. Otherwise I have a collection of books on the subject and have an interest in both the mythology and reality of the phenomenon. When living on Long Island we had a local event in Southaven Park and I had an interesting time relating with folks in regard of that, including a brief exchange with John Ford, who seemed to think I may have been an FBI informant. I also learned about photon proton cannons and alien-human breeding programs. Despite the fringe social aspects, the fact that something unexplainable is occurring and just how people react to it is worthy of study. Also to note, during the more recent drone sighting events, I saw one and spent nearly twenty minutes watching it.