There’s a Van Gogh quote that’s always stuck with me:

“I am seeking, I am striving, I am in it with all my heart.”

Written in a letter to his brother Theo, what Van Gogh means by “it” is clear — his artistic practice. But what his search entails is more open to interpretation — as well as application. Lonesome Vincent had his needs, and other artists theirs. Where, then, and how should artists search? Within? Without? Both?

Van Gogh would assuredly say both: that in making art one should look everywhere for beauty, meaning, and purpose. But how that “both” manifests always varies from person to person. Some are drawn primarily into their minds, toward cultivating their own interiority. Others find inspiration mostly in the world, through maximizing and romanticizing their outside experiences.

These inspirations and aspirations often overlap, and when they do, “scenes” are formed — clusters of like-minded artists, or aesthetes, with shared ideas and opinions about art and their surroundings, organizing under a common ethos.

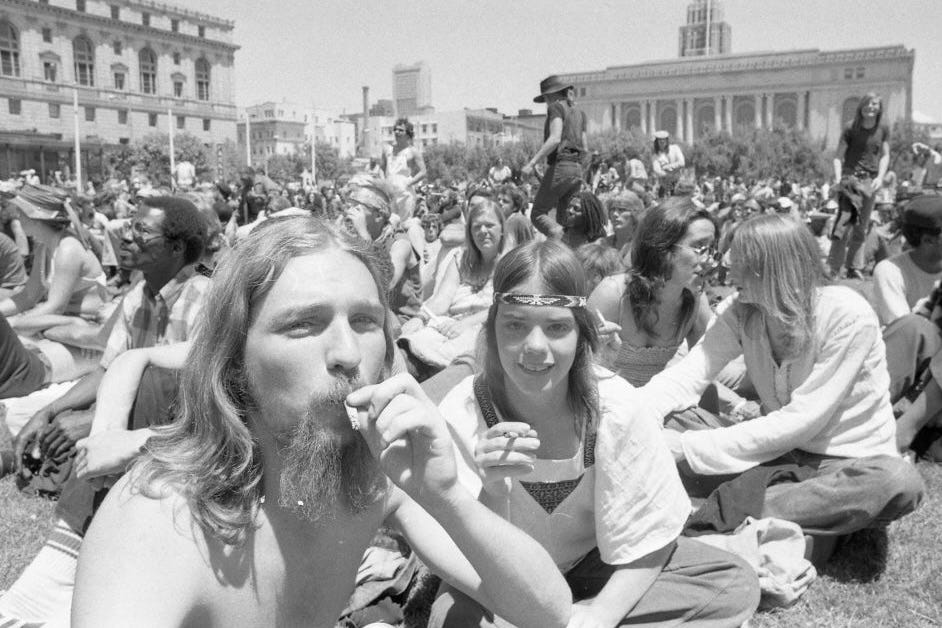

WannaBeat is a novel concerning such scenes and artists’ search for them. Authored by fifty-year veteran “scenester” David Polonoff, an attendee of both the 1970s Yale protests and Matthew Gasda’s 2020s plays, WannaBeat is a heartful exhumation of mid-1970s San Francisco, a cultural moment bridging the beatniks and hippies with the punks and techies. Coming as America enters another transitory time, and as a new generation of self-mythologizing artists has garnered media attention and notoriety in recent years, it offers an excellent autopsy of the benefits and pitfalls of scenes.

Part roman à clef, part memoir, WannaBeat is a sentimental work with much merit. In reading it last year, I felt an uncomfortable kinship with Phillip Polarov, the thinly veiled stand-in protagonist for Polonoff. Here, fifty years in the past, is a man who, like me, foregoes material certainties in the hope of realizing creative greatness, but who, also like me, is all too often caught up in the admittedly entertaining and addicting chaos of the “characters” and circumstances around him. Polarov’s fantasies run wild, at times fixating on his hypothetical Great American Novel — a reimagining of his friends and experiences during the California Gold Rush, which he believes will propel him to the first rank of literary stardom. But his project is never completed, as he falls victim to his book’s dreaded villain, one he himself writes into existence: El Nihilismo. It’s a cautionary tale if ever there was one.

However, while Polarov’s failure largely rests in his inability to focus on his craft, he can’t be labeled a scenester — at least not like I can. His life and Polonoff’s portrayal of mid-1970s San Francisco are richly textured, featuring famous artist haunts like City Lights Books, Caffe Trieste, and Vesuvio Cafe, and they abound with interesting companions and famous cameos — most memorably, a young Kathy Acker, a hammered Gregory Corso, and pre-IPO Steves Woz and Jobs. But Polarov is continually searching for external meaning, some idealized community of similar thinkers in which to find purpose: his perfect scene, or the ingredients — people — with which to build his perfect scene. He scours the city, gadflying a series of disparate ones — the North Beach Baby Beats, the Grand Piano poets, the Grand Street punks — but none satiate him fully, and are often made the subject of his humorous criticisms, if not outright derisions. Polarov is not, however, deluded by illusions of superiority, affectionately labeling much of his own writing as “streams of drivel.”

But whatever the character Polarov’s dissatisfactions, the writer Polonoff — through his novel’s episodic, fragmented architecture, and vivid, conversational prose — weaves a compelling, eulogistic portrait of a city lost to history. Though Polarov at points idealizes a San Francisco of the past, he is still the resident of a city with a beating cultural pulse, one not yet in the all-encompassing thrall of Big Tech. Growing up nearby, I longed for that version of San Francisco, and frequently ventured there to experience its vestiges. But even though I could spot the occasional hippy in the Haight, listen to the Dead in the Mission, and smoke weed in Dolores Park, their long-haired, round-glasses-wearing denizens weren’t artists or bohemians, but software engineers and product mommies dressed in chic vintage. Mere boho kayfabe. Most real artists had long been priced out and scattered elsewhere without replacement. A city of Don Quixotes had become one of Don Drapers — albeit in Patagonia and Hoka, not suits and Oxfords.

In WannaBeat, an interesting harbinger of this transformation comes in the character of Danny Polarov, Phillip’s ill-fated younger brother. Tall, suave, and good-looking, Danny moves to town midway through the novel to find work in Silicon Valley. He captivates Phillip’s diverse, bohemian crowd — an apt metaphor for San Francisco’s eventual destiny and perhaps bohemia overall.

Having spent the last several years enmeshed in the oft-derided Downtown New York scene, I’ve come to the conclusion that these groupings are mostly traps, at least in their supposed purposes. They’re fun, sure, and there’s some professional value that comes from the connections made, but scant few involved are able to balance these benefits with actual creative production — and what little gets produced is often shallow or derivative. You become too easily distractible, too lost in like-minded people. There’s always another reading, another show. A new object for lust and limerence. A new drama to gossip about. It’s no mystery why autofiction is the common currency of expression in these environments; it’s one of the easiest forms harnessed to keep up the appearance of creative output. But even then it’s rarely done with merit, usually as another forgettable “written-for-performance” outpouring of the in-group’s “relatable” myopic hedonism. I had bad sex. I did good ketamine. Then I had bad sex again. Et cetera, ad nauseum. Everyone is too high on the idea of themselves, if not too high in general. You can’t be “in it with all your heart.” It’s impossible. There’s no time. You can’t miss the next event.

While reading and rereading the novel, I repeatedly considered the contemporary state of the professional and aspirant artist class. Where would a man like Phillip Polarov find himself today? Where would he go seeking, striving? After the events of the book, his real-life counterpart wound up in New York City, working for the East Village Eye and reading on cards with Jay McInerney. Perhaps that still is the answer — it was for me, if I’m any analogue. But still, it’s an imperfect, fraught choice. Since the Beats, underground San Francisco was always the alternative to the world of competitive, institutional New York, a place where artists congregated en masse to reject its crafted commercialism. But that San Francisco no longer exists, and while its spirit exists in New York too, the city does not embody it. And it’s not as if New York is that much more hospitable. In the 1970s, Polarov subsists doing sporadic odd jobs and paying for cheap, changing lodgings. Today, the average price to rent a room in Manhattan is well north of $1,500, with Brooklyn not much less, and jobs which can pay for such expenses — and still grant enough time to create — are scarce and competitive. As has been commonly reported, these conditions have made artistic pursuits even more a luxury of the rich. Phillip Polarovs need not bother.

And maybe Polarov wouldn’t. I’d imagine most don’t. Maybe instead he’d be somewhere cheap, deep in the boonies — far out but posting his “streams of drivel” on Substack while submitting in vain to cliquey alt-lit publications. If he’d bother with writing at all, that is.

But that’d be a sad, if conceivable, fate for such an earnest, timeless dreamer.

Even if the art comes infrequently or is mediocre, may we hope for circumstances like those in WannaBeat again. For more Phillip Polarovs. For more searching. We need it as evidence that our culture remains alive.

Nick Dove is a writer and photographer based in New York City. He writes the Substack Above Town, and his work has appeared in VICE, Air Mail, Office Magazine, ExPat Press, and Hobart, among others. He is at work on his own bohemian novel.

Nice piece.

Very nice review. You made me realize I met Polonoff at BCTR -- need to read the book. I think the idea of the scene, of bohemia, is itself romantic, with some of the weaknesses that implies. I discussed that briefly in relation to Gasda's The Sleepers (and in relation to all my NYC friends' obsessions with NYC). I think the real work is getting done elsewhere, at least what work I get done, gets done elsewhere. NYC has too many worthy distractions, plus my day job. Again, very good review.

https://open.substack.com/pub/davidawestbrook/p/new-york-existential-gm-gatsby-veblen?r=13evep&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false