Exile's Reign

On Gerald Howard’s ‘The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature’

“The Mysticism of Money”: that was the brassily alliterative title of a 1922 essay published by Harold Loeb in Broom, the magazine he co-founded and bankrolled. Contemporary American culture, Loeb observed, had positioned commerce as its new religion. Europeans made money as a means to old-school ends; Americans had started to make it for the sake of making it. This was strange and unsettling, but the upside was an emerging metropolitan culture of startling energy — as Loeb put it, “vigorous, crude, expressive, alive with metaphors, Rabelaisian.” You could object to the economic system underpinning this boom, its inequities and vulgarities, but there was no denying its vitality.

Aged 24 when he read Loeb’s essay, Malcolm Cowley sat up. By the end of his long life he had become a fixture of the American metropolis, a grand old man of the New York literary establishment. But his roots — as he puts it in Exile’s Return (1934), the first and most enduringly popular of his nonfiction books — were “west of the mountains,” in the hilly woods and streams of Cambria County, Pennsylvania. He was often exasperated with America, and for long stretches found himself radically at odds with its prevailing political mood. But he never fell out of love with his country, in the sense of its places and people. When he read Loeb’s essay he was living in France, during two formative years among the much-mythicized community of expatriate Americans. Perhaps Loeb’s paean to America made him homesick; it definitely clarified his vision of his life’s work.

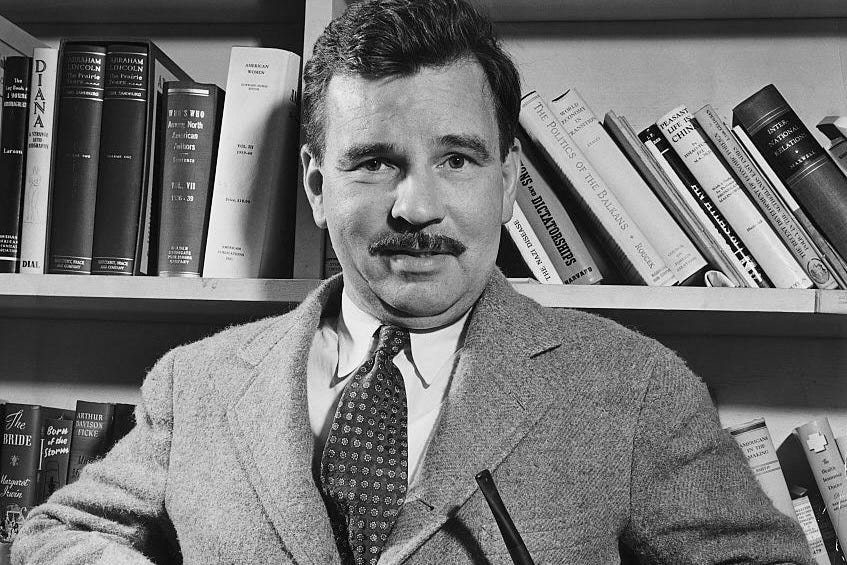

During his schooldays at Peabody High in Pittsburgh, Cowley fantasized of becoming a newspaper’s theatre critic. As it happened, his literary career scaled greater heights. He played a central role in the formation of the 20th century American canon. As Gerald Howard shows in this lucid and enthralling biography, The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature, there’s a persuasive case to be made that — as professional critic, political activist, essayist and editor — his was the central role.

Cowley strove unflaggingly for a genuinely modern and authentically American literature, and a world in which those two qualities did not exist in tension. He wanted a new scene, a subculture within American letters, which would speak to the alienated generation born around 1900 and confirm Loeb’s sense that the restlessly innovative national spirit might manifest itself in modern works of art as well as in railroads and skyscrapers. But this wasn’t going to happen by magic. It needed men of letters — they were mostly men, mostly white and middle-class — to bring it to fruition.

The Americanist Barry Shank defined a scene as an “overproductive signifying community.” Scenes arise, according to this theory, when a physical place (Shank is writing about rock music in postwar Austin) produces more energy than can be conventionally absorbed by existing cultural structures. This kind of bottom-up, sociological explanation has become dominant in Anglophone analysis of cultural scenes, even premodern ones: the explosion of literature in late Elizabethan England, for example, is typically explained as the frustrated spillover of a generation of minds educated for civic and administrative positions which, in a fragile economy and stagnant political culture, did not exist.

Howard’s biography is not the first of Cowley — it follows (and gracefully acknowledges) Hans Bak’s pioneering study, whose first volume appeared in 1993. Howard sets out explicitly, though, to tell the story of the “Cowley era.” His focus is not so much a single life as that life’s achievements “on behalf of American writing.” Against the grain of sociological, bottom-up approaches to cultural history like Shank’s, The Insider argues that cultural production does not just happen. The various scenes that compose a literary culture are made, not born; if they crystallize or coalesce, it’s thanks to the vision and determination of certain persons. Scenes might escape the confines of traditional cultural institutions, but sooner or later they produce their own hierarchies of association, their own rules and regulations. Twentieth-century American literary culture was a system — informal, provisional, protean, but a system nevertheless. All systems ask to be played, and Cowley was one of the key players.

Howard narrates the Cowley era’s arc in three acts, the first two of which correspond roughly to the two interwar decades. When Cowley arrived in Paris in 1921 for his busy stint of criticism-writing, Europe-observing, and café-haunting, he was returning to a continent he’d first known as a battlefield. In 1917 he had interrupted his studies at Harvard (he’d published poems and reviews in the Advocate, whose editors grandly came out in favor of the Allies) to serve as a camion driver at the front — like Hemingway and Dos Passos, with whom he’d associate on the Left Bank. He stayed in France until 1923, establishing himself in the precarious but lively ecosystem of transatlantic magazines; after completing a scholarly thesis on Racine in Montpelier he returned to New York, and eked out a living as a professional critic. Times were hard, but his work bore fruit: in 1929 he published his collection of poems, Blue Juniata, and the following spring was elected to the board of the New Republic, as Associate Editor in charge of the “back of the book,” the section for reviews and cultural essays.

In 1921 the Literary Review of the New York Evening Post (a journal untroubled by character-limited digital name fields) published Cowley’s essay “This Youngest Generation.” It contained his “once-in-a-lifetime bolt of intuition about his generational cohort,” on which Exile’s Return would expand. The generation born around 1900, Cowley proposed, was distinguished by time because it was unusually alienated from place: cultural differences between America’s regions, even in the south, had worn away, replaced by a uniform Americanness cultivated by a homogenizing education system. In other words, America was having its 19th century cultural-nationhood phase. The displacing effect of the Great War, therefore, accentuated a pre-existing generational rupture. This is one of several instances in which Howard shows Cowley’s talent for laying his finger on the cultural pulse, his ability to diagnose the contemporary condition as well as mold literary responses to it.

Howard draws out, with an assured grasp of his material and an analytical lightness of touch, some productive paradoxes in Cowley’s theorizing. The camion-driving generation rebelled against their parents by spurning Henry James in favor of bolder European literature. Yet they also rejected 19th-century America’s tendency to position itself as a cultural province of Europe. The truly American literature Cowley was searching for would throw off the shackles of European manners as well as New-World Puritan morality — but the seeds of that emancipated, self-possessed flowering would be discovered across the Atlantic. In the mid-1920s Cowley felt more excitement about Dadaism than the early work of Hemingway; his collaboration with Matthew Josephson on the transatlantic magazine Secession represents a futile but instructive attempt to import Dada aesthetics into the USA. The problem, Cowley discovered on his return, was that in New York the budding Dadaist is vulnerable to being snapped up as a copywriter for an advertising company.

“Solvitur ambulando,” read the inscription of a book given to Cowley by his Harvard composition instructor, Charles T. Copeland, before his departure for the war: it is solved by walking. Attributed to Augustine, the phrase’s original connotation is of the puzzled scholar’s head-clearing stroll. Cowley’s expedition, as Copeland knew, would be more adventurous. The “Youngest Generation” sought to correct what they saw as a cloistering tendency in the first modernist wave — the movement often known as Symbolism, which Cowley’s contemporary Edmund Wilson would portray in Axel’s Castle (1931) as a reassertion of Romantic aesthetics for a post-Darwinian age. Cowley’s reservations about Symbolism are epitomized by his reaction to the death of Proust. “His own death was only a process of externalisation,” he writes in a 1922 essay for The Dial; “he had turned himself inside out like an orange and sucked it dry.” If they wanted to hold the mirror up to 20th-century nature, younger writers would need to forsake Proust’s method and get out more. Amy Lowell, who met Cowley at the Harvard Poetry Society and liked his poems, expressed this need as the Imagist value of “externality,” a focus not on the Proustian out-turned self, but instead on “things for themselves and not because of the effect they have upon oneself.”

The need for externality also meant that literature could learn from investigative journalism. But ambulando in this sense, of the reporter’s shoe leather on the sidewalk, risked lapsing into something more aloof — the detached wandering of the European flâneur. An American writer, Cowley discovered in the 1920s, has to balance the twin imperatives of making a living and remaining free from the soul-crushing mechanism of industrial capitalist society. The risk of cutting loose, though, is confinement to the sidelines. In a 1929 essay on Hemingway, Cowley proposes that his generation had adopted a “spectatorial attitude” towards the Great War. “Incompletely demobilized,” they had not grown out of it. They were sharp, disabused observers of modern life, but maybe observation was not enough.

In Howard’s telling, the second act of Cowley’s career began when he responded to this nagging desire for a socially-committed literature. The Wall Street crash expunged complacency from establishment political discourse and thrust radical alternatives into the limelight; the suffering unleashed by the subsequent recession made aloofness a difficult attitude for writers to sustain. Cowley’s leftism was sincere and his dedication to activism impressive. In 1931, as part of a squadron of writers and journalists assembled by Theodore Dreiser’s National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, he visited Kentucky to witness the miners’ strike in the eastern part of the state. After violence flared in Harlan County during the violent crackdown, Cowley returned with another committee. They were met with intimidation, denounced as “revolutionary Bolsheviks from New York.” Howard brings the scene vividly to life: Cowley staying cool in the face of thuggish strikebreakers trying to spoil supplies transported for the miners’ relief; ensuring that the Paramount cameraman’s film made it safely across state lines.

Cowley’s leftism was always of this engaged, activist kind. He avoided joining the Communist Party outright, instead affiliating with subsidiary groups like Dreiser’s. Rather than a writer suddenly jilting their first love of literature for an affair with politics, Howard depicts a man of letters compelled by acute circumstances to pay attention to the material crises in his country. Communism remained for Cowley a means to the end of allaying the hardness — longstandingly spiritual as well as, with recent urgency, material — of American life. “Art and culture,” declared Cowley in a state-of-the-nation address at the inaugural American Writers’ Congress in 1935, “cannot live in such a world.” He took only limited interest in the proletarian literature championed by more doctrinaire Communists like Mike Gold. What the novel could borrow from Marxism, Cowley thought, was not its ideological rigidity but its commitment to “grappling with the social world.” He held up Dos Passos as the shining example of a novelist who grappled, whose work uncovered the “huge, impersonal forces” governing American society, but also the way those forces could “shape and warp individual destinies.” In other words — and in the expanded, diluted sense of Tom LeClair’s original term — the systems novel.

That Cowley seems so perceptive on the divergent radicalisms of art and politics makes it all the more troubling that he became, for a considerable chunk of the 1930s, an apologist for Joseph Stalin. Young American readers had gobbled up Exile’s Return, fascinated by its cultural analysis and evocations of literary Paris — but gnarled conservative critics took exception to the fecklessness of Cowley’s generation and the naivety of their leftism. Across the 1930s, Cowley’s defense of the Soviet Union and its proxies grew more entrenched. Unlike Hemingway, he did not travel to Spain to witness the Civil War firsthand, but was anxious in this next European conflict to adopt something other than a “spectatorial attitude.” When violence broke out between factions of the antifascist coalition, Cowley sided with the Soviet-backed Popular Front, turning a blind eye to their ruthless purge of Trotskyist and anarcho-syndicalist groups. He responded to the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial, in which 16 veteran Bolsheviks were condemned to death as Trotskyist conspirators, with expressions of support for the Soviet government.

There’s no escaping or qualifying the enormity of Cowley’s misjudgment. But it’s worth noting that a biography of a well-intentioned person of letters who had toyed with supporting 20th-century Europe’s other murderous tyrant-in-chief — even fleetingly, like Cowley — would be a much harder sell. An indulgence still operates in what used to be called (until, say, January 2026) as “the West,” towards intellectuals who brushed with Stalinism, as distinct from Marxism or Communism: they weren’t to know the full extent of the horrors, goes the party line, or the severest of the supposedly unintended consequences. No such largesse exists — with one major, warmongering exception — in the progressive circles of Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet world. Yet we tend to neglect those alternative perspectives. In a rare but repeated instance of blurriness, Howard describes American leftists travelling to the 1929 International Congress, and then a conference on revolutionary literature, to Kharkov, a city located “in Russia” — except that Kharkov, now Kharkiv, has always been a Ukrainian city, and was from 1919 - 1934 the capital of the Ukrainian SSR.

Nevertheless, Howard navigates this episode well, achieving a skilful balance between sticking up for his man and taking care not to defend the indefensible. This reasonable partiality is a feature of The Insider as a whole; Howard champions Cowley without letting affection distort his judgment. Many of Cowley’s contemporaries, both friends and adversaries, analyzed his Stalinist mistake as a classic case of someone confusing politics and literature. In a ferocious demolition job for New Militant, Felix Morrow diagnosed Cowley’s apology for Stalin and hostility to New York Trotskyism as an instance of “the lost generation’s distrust of ideas and contempt for abstract thought.” (In full Temperance Preacher-mode, Morrow also condemned the New York literary scene’s fondness for “gin, fornication and dandified rowdyism”; I’ll have what they’re having, wavering young Trotskyists might have secretly thought.) Wilson, in the mirror image of Morrow’s argument, accused Cowley of setting too much store, rather than too little, by ideas: “politics is bad for you,” he told Cowley, “because it’s not real to you.”

The literary man whose understanding of politics is insufficiently abstract, but who at the same time treats politics as an exclusively discursive affair, a game of arguments: that guy got around in the early 20th century, and walks among us still. It’s true that Cowley’s faith in Stalin rested on textual accounts whose authority trumped empirical reality: “people who ought to know,” he comments on the Robles affair (the 1937 summary execution of a Republican writer in Spain on NKVD orders), “tell me that the evidence against him was absolutely damning.” But Howard’s narrative suggests another interpretation. Cowley’s reluctance to see Stalinism for the grotesque tyranny it was stemmed fundamentally from his desperation to see radical spirit, of both literary and political form, manifest itself in the real world. He criticized the New York Trotskyists, hammering out their positions in the early issues of Partisan Review, not principally for their theoretical abstraction and austerity of style, and still less so on the Stalinist grounds of being crypto-“rightists”, but because in opposing the Soviet state the Trotskyists were undermining the only modern alternative to the economic system tearing American society apart. “On the political scene,” Morrow speculated, Soviet communism for Cowley’s generation “corresponded to what surrealisme represented on the literary scene.” Morrow got this subtly but significantly wrong, Howard suggests: Cowley’s appalling indulgence of Stalinism derived not from a dogmatic commitment not to the avant-garde itself, but rather from stubborn and beleaguered faith in the avant-garde’s original promise of material change in the real future.

Cowley’s earnest commitment to Communism, his belief in its capacity to transform American life wholesale, sets his attitude to the social relations of his own trade in a strange light. Cowley slotted into Manhattan white-collar life happily: at the New Republic offices, “on West Twenty-First Street in a placid corner of Chelsea,” he took breaks for games of “deck tennis in the backyard” and enjoyed the “excellent lunches prepared by the cook, Lucie.” In 1935 the magazine moved north to elegant Modernist premises in Midtown, designed by the architect William Lescaze. In “disguise as a junior executive,” Cowley claimed to feel “like a spy in enemy country.” But he was also a content half-week commuter with a house and garden in Connecticut, happily married to Muriel (his first marriage, to Peggy Baird, had ended in 1931) and recently a father. Comfortable with bourgeois rhythms of work and structures of family life, Cowley also thrived in the hierarchies of the New York literary scene — whose form, individualistic and hyper-competitive, was about as non-Communist as could be, whatever specific beliefs its members espoused. Cowley was generous as well as tenacious, trying where possible to find work for impecunious young reviewers promoting themselves to the New Republic. He wanted the hierarchy to work constructively. But he didn’t question its existence.

This complex tension, between radical positions and the thoroughly bourgeois patterns of a life spent promoting them, surfaces particularly in Howard’s occasional references to sport. Cowley’s self-fashioning as a New York intellectual with simple country roots doesn’t seem to have drawn much on the athletic parts of American popular culture — though Bak’s biography informs us that, as a freshman at Harvard, Cowley enjoyed throwing his hat over the crossbar after Harvard defeated Yale 41-0 in the 1915 derby; he also felt a frisson when his friend Hart Crane played “Très Moutarde” on the piano, as it had supplied the tune for his high school football song. In the late 1920s, for a series sponsored by bookstore chain Brentano’s, Cowley wrote an admiring profile of Ring Lardner, author of short stories and sports columns. Lardner’s engagement with the quotidian immediacy of sport made him appealingly modern. The Insider draws on sport less for its immediacy than for its availability as a metaphor for the struggles and contests of a literary career. “Here we have the material for a searching work,” proclaimed Louis Untermeyer in a review of Blue Juniata in 1929, “and the author does not fumble his chance.” Howard himself, describing the Communist party’s charm offensive against Cowley in the mid-1930s, reaches for a baseball analogy: “it was time to bring the major leaguers onto the field.”

Sport is a rich, ambivalent metaphor for the competitiveness inherent to a literary career. It might stand for the hustling, ruthless ultra-competition some persons of letters swear by. Alternatively, it might connote healthy competition and fair play, the ideal of a level field in which skill and application go unusually far. In this second sense, a sporting attitude seems compatible with the values of the literary Communist. But the literary Communist who believes uncritically in hustling is beset by contradictions.

The Insider’s final third narrates the last act of Cowley’s career. A profusion of nonfiction writing — more essays and reviews, a second edition of Exile’s Return, and several new nonfiction books — restored the trust and status he had lost in the rancorous 1930s. Most significantly, Cowley secured a position as an Advisory Editor for Viking. Harold Guinzburg, Viking’s founder, offered him the job in 1949, and it proved a smart decision: as Howard tells it, Cowley made four interventions that had a lasting impact on the 20th-century American canon.

The postwar decades were the most settled and tranquil of Cowley’s life. Accordingly, Howard’s narration starts to flit more freely between periods, breaking strict chronology to carry forward a relationship forged in the 1950s to its conclusion decades later, or setting a single event in the context of Cowley’s formative experiences in the 1920s. It’s an astute choice, a structural reflection of the tendency in later life to look both forward and back. But Cowley owed his success and happiness to an act of aristocratic benevolence. The Second World War had dealt him severe personal and reputational blows; he had been stripped of editorial responsibilities at the New Republic. Cowley’s rescuer was Mary Conover Mellon, who with her husband Paul had set up the Bollingen Foundation, originally to promote the work of Carl Jung. Seeking to expand its scope as American society contemplated the coming era of supremacy, the Foundation awarded Cowley a generous five-year stipend (officially and bizarrely called a “Five-Year Plan”; Howard lets the irony speak for itself) to use as he saw fit. As Howard puts it, Cowley “was able to woodshed — to read attentively, meditatively, voluminously, constantly, encyclopedically.”

Cowley made inspired rediscoveries and harnessed creative ways to share them with an expanding reading public. In 1943, the Council on Books in Wartime had started producing their Armed Services Editions: slim paperbacks, brightly colored and double-columned, marketed to American troops. It was a wild success; wedged into uniform pockets, the books cushioned Nazi bullets at the Normandy landings. Viking, keen to surf the wave, started issuing its own pocket paperbacks, and the Portable Library was born. During his five years of woodshedding Cowley had returned to Hemingway, and now for the Portable series he edited a selection. In a single stroke Cowley’s introduction altered America’s idea of the Lost Generation’s original headline act.

Hemingway had come to be seen as a painterly Naturalist of clean surfaces. Cowley aimed to expose the shallowness of this view, and reveal the Symbolist Hemingway, the poetic intensity lurking around the edges of his traumatized and vagrant characters. This was a Hemingway of still waters running deep; a lifelong angler, Cowley in the Portable introduction compares the experience of rereading Hemingway to revisiting an old fishing spot, and finding the woods “as deep and cool as they used to be.” Re-establishing his friend as a modernist, Cowley’s edition “rendered Hemingway teachable.” It also transformed understanding of his style, revealing the potency of what his granite-hard sentences left unsaid. In the master’s hands, a concise and economic style was good not only for describing things, but also for suggesting subtext and resonance. Whether any other writers could follow suit, and thus whether this reframing helped American literature march on, is a different question.

The second rediscovery was an unambiguous triumph of canon-adjustment. By the 1940s, William Faulkner’s career had apparently run its course. Cowley single-handedly revived it, first with critical essays and then with another Portable selection. His correspondence with Faulkner shows tact and patience, which paid off: the reclusive Faulkner engaged with the project, and ensured that it became something more collaborative and original than a standard miscellany. Cowley’s idea was to focus on Yoknapatawpha County, Faulkner’s mythical version of his Mississippi homeland. Faulkner supplied a map (“Surveyed . . . for this volume”) as well as a family tree, stretching back to Culloden in 1745, of The Sound and the Fury’s Compson family. “The job is splendid,” he told Cowley by letter after publication, “damn you to hell anyway” — Faulkner-speak for “thanks so much.”

Cowley’s work on the edition was a “magnificent example,” Howard comments, “of selfless, disinterested generosity on the part of one writer to another.” This is true, and you sense the compliment’s sincere warmth. But Cowley’s acts of “disinterested” generosity were also carried out on behalf of American letters, in whose health his interest was considerable. “I like and love the American literature,” he says in “Hemingway’s Wound” (a late essay where he also self-defines as a “little American”), “even while feeling that its past is still in process of creation, not to mention its future.”

The Portable selection presented Faulkner as a folklorist, Howard says — “a bard, a teller of tales” who would remind genteel readers or GIs that their cheerily confident, newly supreme America was built on the swamps of dreams of fantasies, many of them premodern and some, like slavery, ugly and unmastered. For all his rootedness in the South, Cowley thought Faulkner most resembled Hawthorne. In the Portable Hemingway he had grouped Hawthorne with Poe and Melville as “haunted nocturnal writers . . . who dealt in images that were symbols of an inner world.” His editions of Hemingway and Faulkner equipped him with the start of an answer to the question of literature’s place in the new era of American ascendancy. Communism had lost all credibility and American capitalism was flourishing. Literature could not bring about the system’s overthrow; what it could do was humanize the American experience, by showing up the darkness and unmastered history hiding in the system’s cracks.

Cowley’s third editorial triumph was the part he played in Jack Kerouac’s long struggle for publication. Howard, who retired in 2021 after a distinguished career as an editor for Doubleday, gives a sparkling inside account of On the Road’s, well, road to publication. The young Kerouac was a self under construction, dressed in a “rented tux” for “steak dinners” with Robert Giroux, editor of his first novel, The Town and the City (1950). But it was Cowley who read the first draft of On The Road for Viking, fought its case with doubtful colleagues, and persevered for years until, in 1957, the novel was published. He had help from Helen Taylor, Viking’s in-house copy-editor, “strict and cautious” but also an open-minded expert who knew good prose when she saw it; it was Taylor who “put the clamps” on Kerouac’s freewheeling style, checking the flow with commas, in the novel’s first edition. Howard achieves a fascinating portrait, authoritative but non-institutionalized, of postwar American publishing culture, and demonstrates the usefulness of writing modern literary history from inside — of understanding writers not as isolated witnesses, lone refractors of zeitgeist and vibe, but rather as actors within complex internal ecosystems.

Writing up On the Road in Viking’s catalogue, Cowley compared Kerouac’s Beats to his own (now aging) Youngest Generation. In the 1920s the exiles had sought the avant-garde spirit in France; now, in the second war’s wake, a similar ragtag group was “roaming America in a wild, desperate search for identity and purpose.” But there were differences. The intra-American pilgrimages of the Beats contained a spiritual dimension (Kerouac was a singular mix of Catholic and Buddhist, as well as a nihilist rebel) “entirely alien to the Lost Generation,” just as, to the Beats, that older grouping’s commitment to organized leftism seemed quaint. Like Dos Passos, the Beats were responding to structural forces in American life. But they depicted those forces in mystical rather than political terms. The material leftism of the socially attuned, “grappling” novelist had been sublimated — just as it would be on the right, decades later, when the paranoid anti-Communism of the postwar period morphed into evangelism and conspiracy theory, and then took control of an obliging Republican party.

The retreat of literature — that is, commercially viable literary fiction marketed to white professionals — from politics coincided with literature’s entry into a rapidly expanding university system. The postwar period was the beginning, as Howard notes, of what Mark McGurl calls the “Program Era,” where creative writing emerged as a university discipline. About the compatibility of literary and academic culture Cowley had his reservations, but he accepted invitations to instruct on several programs and taught “diligently, if less formally than a credentialed academic might.” His workshops at Stanford included a powerfully-built young man working on a story about a mental institution and its sinister methods of mind control — once again, oppression of a spiritual rather than explicitly political kind. Reading the early drafts, Cowley put his considerable critical weight behind the novel that became One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

As anyone who has spent five minutes on literary Substack knows, few topics attract rancorous heat like the influence of MFA programs in creative writing. It’s easy to mock creative writing as a discipline, to depict the horseshoe of graduate students in a seminar room as a sterile, artificial replacement for a spontaneous gathering in a Parisian café. The founding father of Stanford’s program was the novelist Wallace Stegner. His wife, Mary, remembered him remarking of the married veterans arriving at Stanford on GI Bill funding, that they “needed a place where they could write and talk, like a coffee house in Europe.” Stegner’s remark demonstrates a modern uncertainty about the public sphere, a hankering after “third spaces” that belies their precariousness under capitalism. It’s the same haziness that underpins the contemporary American use of “community” to mean “people online who agree with me.”

At its worst, Cowley thought, the MFA steered young writers towards rectitude and away from life. He hated the metafictions of the John Barth school, quipping that “the books themselves seem long-haired and bearded”; he also criticized contemporary novels for being unpeopled. Yet if the rise of university creative writing risked sterilizing literature, it also — as Cowley saw firsthand, in Kesey’s case — could provide outsiders with a path to publication more certain and less luck-dependent than in previous generations.

On the whole, Howard shares Cowley’s nervousness about separating the real world from the world of books. Both author and subject seem ambivalent about the school which came to dominate the postwar study of English literature: “those symbol hunters, the New Critics.” As practiced by luminaries like Cleanth Brooks, Yvor Winters, and W. K. Wimsatt, New Criticism combined a receptivity to symbol and ambiguity with an ethic of painstaking, close textual attention. The problem, Cowley argued in The Literary Situation (1956), was an over-emphasis on being perfect, and a bias toward texts whose perfection showed up under the critic’s microscope.

It’s true that the most “teachable” writing is not always the best, and that New Criticism at its driest seemed positively hostile to the artistic temperament. There is such a thing (certain contemporary novels remind us) as writing for critical explication, and it’s a blight. But New Criticism was practized not only in order to train the next generation of American novelists; literary studies exists — and continues to, just about — for its own ends. New Criticism laid the foundation for an extraordinary profusion, beginning in the 1960s, by American academic critics. Studies in this tradition range adventurously, often beginning in the European Middle Ages and ending in the Lost Generation or even with the Beats. These books played their own part in the great humanist project to which Cowley also contributed, of representing America to itself by revealing where it stood in the long perspectives of global space and time.

Setting academic and professional criticism at cross-purposes, Howard perhaps projects a characteristic of our own times onto the recent past. These days professors and publishers, even of literary fiction, have oddly little to do with one another. But it wasn’t always the case. The English poet Geoffrey Hill considered 1925 - 1965 “the high period of American literary criticism.” Hill names R. P. Blackmur and Lionel Trilling among the heroes of this golden age, which coincides with the most influential period of Cowley’s own career. Critics like Blackmur moved easily between universities and literary journals, and wrote in an all-purpose idiom which eschewed both jargon and cultural populism.

Cowley himself wrote in this idiom. His critical voice is assured, serious, effortlessly in command of its material. He doesn’t pander, as some critics did then and do now, to what might be called the Implied Airhead Reader. But he does write personally, without the contemporary academic pretense to objectivity. “Reading the book for the first time,” he remarks in his 1943 review of Eliot’s Four Quartets, “I remembered the Swedenborgian sermons to which I half-listened every Sunday morning during my boyhood; I didn’t grasp their meaning, but . . . went home to dinner with a pleasurable feeling of elevation.” But this folksiness is backed up by deep, careful engagement, and most importantly — for the hawkish, performatively unhoodwinkable critics of today — by what Hill calls “a form of love, a sense that to seek to penetrate the mystery of how and why works of literature succeed or fail is to do work of inestimable value.”

Few professional critics working today have time to develop Cowley’s depth; no one outside the academy receives five years’ funding just to read books. Meanwhile, almost no one in the Anglophone academy can survive if they spread themselves across a range as wide as Cowley’s. Yet as Howard’s analysis of Cowley’s Stalinist blunder shows, range has its pitfalls. Highly proficient at zooming in, Cowley always zoomed back out to consider texts in the broad context of American literature and the broader context of American society. We can admire the humanist preoccupation with literature as societal lifeblood, but we should also note that Cowley found it easy to encompass society because he failed to take so much of it in. If his engagement with the proletarian novel was fleeting, his consideration of race and gender was negligible. He admired some work by Black writers, such as Ellison’s Invisible Man, but both his aesthetics and his politics were shot through with a universalism effacing of difference, and it’s this same breezy universalism that allowed him to co-author, with Daniel P. Mannix, a general history of the Atlantic slave trade.

This is Howard’s first full-length book, but he has written numerous essays over the years, on contemporary literature and the lives and times of its publishers. His essays crackle with wit, cutting their astute observations with self-deprecating asides and abrupt high-to-low tonal bounces. The Insider deploys this verbal fun stuff sparingly, but judiciously: “no wonder young people hate adults,” Howard comments after quoting from a snotnosed review of On The Road by Robert Ruark (“a sub-Hemingway novelist of the manly man variety”). He goes to town in the acknowledgments, by far the most entertaining section of its kind in any recent literary biography. He thanks Helen Rouner, his own editor at Penguin, for her patience “as I have learned the difficult skill of becoming an author (insert ironic horse laugh here).” And he takes dead aim at the “sloppy bureaucrats at the Federal Bureau of Investigation” who stonewalled his request for Cowley’s files..

Howard exercises restraint, too, in the other direction. His insider methodology, with its emphasis on contingent networks and significant actors, strikes a complementary but refreshing balance with analysis of 20th-century culture overloaded by sociology. On occasion, however, some sociological speculation wouldn’t have gone amiss. Exactly how and why writers like Cowley, white and male but radical in their receptivity to Marxism, were able to overlook so much difference in their conception of American society, is a question the book could have afforded to address. Similarly, the brilliant analysis of Cowley’s rehabilitation of Faulkner points to the richly ambivalent place of the South in the postwar literary imagination: the holdout of white supremacy and grievance, on one hand; on the other, fertile ground for the folkloric, mythical country Cowley wanted to foreground as booming postwar America left behind all its versions of pastoral, however dark.

Reading this book more than a century after Cowley’s formative sojourn in France, it’s natural to wonder about the state of bohemia in our own times. As we all know, times are hard for artists. In 1932, John Cheever (who benefitted, like many others, from Cowley’s generous encouragement) rented a room on Hudson Street for “three dollars a week”: about $280 per month, in today’s money, except the young writer wanting a one-bed on Hudson Street needs about five thousand extra dollars to make their rent. Defying prohibitive conditions, however, scenes continue to form and assert themselves, in New York and throughout the world. You’d have to be a philistine as well as a loser to assert, like Peter Thiel did in 2011, “the collapse of art and literature after 1945.” Doesn’t it kind of suck, though, that even the most radical cultural scenes rely, for their publicity and visibility, on the platforms owned by Thiel’s fellow bootlicking oligarchs — the rocket guy, and the guy with the embarrassing new golden chain?

Substack’s relation to those platforms is another hot topic. Substack’s most progressive feature seems to be its openness, its absence of gatekeeping. Online communities can form on Substack, though they are subject to the same algorithmic warping that makes communities on other platforms so shrill and tribal. More promisingly, Substack’s reach and transparency can be harnessed to the end of cultural scene-construction in the world of material cities — and the rest of us can fantasize about it.

Vladimir Nabokov has only a walk-on part in this book: “I am sick of teaching,” he writes to Edmund Wilson, three times in a row with fed-up artlessness. But this biographer-subject relation has something Nabokovian about it. Howard knew Cowley, and is stylishly economical with personal recollections. His biography is bookended by two personal encounters: in the introduction, as a novice fiction editor in 1981, Howard shakes the hand of a “deaf and elderly” Cowley in the office; in the epilogue, he warmly remembers attending Cowley’s 90th birthday party in Sherman, Connecticut, 1988.

A literary career entails a constant back-and-forth between art and life: fictional characters haunt flesh-and-blood persons; writers express their truest and most feigning selves on the page. Many details of The Insider might have made the author of Pale Fire prick up his ears. At Harvard, Cowley and his friend the poet S. Foster Damon created a literary hoax, a “plowboy poet” called Earl Roppel. In 1944, Cowley restored a good chunk of his literary reputation with a New Yorker profile of the editor Maxwell Perkins; “I wouldn’t mind being like that fellow,” said Perkins of the man in the piece. With a very light touch, but convincingly, Howard chalks up Cowley’s surprising posthumous obscurity to a literary conspiracy: having made so many enemies among both conservatives and Trotskyists, Cowley suffered from the vindictively long memories of New York’s taste-making scenes.

In Nabokov’s hands, this book would become a story of sinister encroachment, as two American men of letters, each with trochaic Scottish-sounding names, stalked and eventually confronted one another. In Howard’s telling, however, the real life of Malcolm Cowley is happy to exult the considerable achievements of its subject, while exhibiting many of the virtues it commends in him. It makes an understated but urgent case for the centrality of persons of letters to a good and decent society; it demonstrates the usefulness of writing cultural history from within. Most of all, it portrays 20th-century American literature in all its glorious vitality.

Archie Cornish is a writer and academic who lives in London. He has published fiction and essays in New Writing, Literary Review, The Fence and others. He writes a Substack called Night Thoughts and is working on his first novel.

The author of THE INSIDER wishes to thank you for this kind and perceptive review. It is very nice to be understood.

Gerald Howard

What a fun read. Really interesting stuff!