They discovered who they would be to each other. Sweet and maternal — her last boyfriend had called her “bean,” or “baby” — or cool and adult. This one would not be her baby. He didn’t seem to want to be, first of all. Second of all she didn’t want him to be. The soft part of her had guided her before and she wanted the hard parts leading now. She was older now, this seemed the lesson of her younger years. Her last relationship had failed for many reasons, among them that she’d found it impossible to be someone’s baby and also to tear fuckably at their clothes.

For his part, he’d tried calling the ex-wife “goose” in their early days but she wouldn't have it, found it alternately unromantic and offensive — which were how she found him, in the end, usually both at once. She walked out on him. Rejected even the couples therapy that seemed to him the least they had been promising when they spoke those vows. (Unless this belief was again mere evidence of his unromanticism.) So he tried the moniker anew with this one. Felt a bit like cheating and a bit like cleaning. Windex the toothpaste-spattered mirror. Both he and the ex-wife had been messy when they lived together. Now his place was spotless. Hers too, he’d heard from a mutual friend. Each blamed the other for their slobbiness. He knew, though, that the act of being clean was itself an act of cleansing the old. The new girl seemed to like it, goose.

She liked “goose” but noticed she had nothing to offer in return. Frequently pulled “baby” back from the brink of her lips. She found it easier to come to pet names for the actual pets. Bambi, because the one that had looked to her at first as though a Nazi child would train it on the babydolls had put its soft chin on her thigh and fallen asleep and thus become, with frightening immediacy, her little favorite. He looked now less like a guard dog and more like a fawn. Much like his owner, who had seemed somehow unready to her upon first meeting, though what exactly had been unready about this handsome new one would forever be a mystery to her now. Bambi, she called the dog, waiting for sleep with him curled into her chest, aware both that she could channel her soft part to him instead of his owner and that there was some frightening truth to the sudden depth of love he’d tunneled into her. She had not signed up for this, she felt. Like the Grinch, she tried to explain to The New One, my heart grew two sizes today, but she knew it was useless. He would think she was exaggerating for purposes of snatching him, oh look what a step-mom I am to the two small creatures, when in fact she was experiencing a kind of love no man had drawn out of her and he seemed unlikely to. Bambi, she said to the dog, into his pointy ear. Bambino, this became, without much effort.

She noticed that she preferred one small creature to the other. That this seemed to pain him. That one’s a reject, he said to her one night, pointing to the other one at the foot of the bed while the Bambino breathed its doggy breath at her breast. Like me, he said. Then he added, We got him from the pound and both his moms walked out on him. Later that day he put the three of them to bed as he did, then got up to play guitar in the other room as he did. At first this had made her feel lonely, had made her wonder why trade a man who held her tenderly as his baby for one who left her alone in his bed, but later she came to like it, the troubadour standing sentinel. She was not sure how good the troubadour would be at defending the terrain against invaders, if it came to that. (The One Before Him had slept with a bat next to the nightstand and one night grabbed it and gone out, ferociously, to find a raccoon skittering through the living room.) But she liked going to sleep with his chords in her ear, pretending he was playing to her, knowing he was probably just playing.

He loved that the dogs loved her. He had called the dogs goose, in truth, in the interim between the ex-wife who rejected the pet name and the new girl who accepted it. It was a name that felt full of affection to him, maybe his mother had used it when he was young before the complications started and the loss. When he first called her goose, he worried she would catch him in the re-cycle, then stopped worrying. Then months into the thing, she was all but living in his bed despite his promise to himself not to make her his girlfriend. (He had a tendency to get wifed up, his friends said, and he wanted to take his dick on somewhat more of a world tour in the interregnum post-divorce.) He was lying with her in the space after sex and before he left for the other room. When you called me the pet name you use for the dogs, she said into his armpit, that was when I knew you wouldn’t disinvite me. (They did not yet say love. They hid it, barely, in double-negatives and gutless workarounds. I opposite-hate you. You don’t disinvite me. You’re the best, you’re my favorite, you’re my goose.) He got up from the bed then, early, knowing it was a punishment to her but mostly embarrassed to have been caught. He waited to hear her stop saying sweet nothings into the ear of the one she called Bambino, which was how he knew she’d fallen asleep. Then he took up the guitar. He played at night like this in part to be alone forever despite his tendency to get wifed up. No woman could match his ability to not-sleep. Not for long, not even in the romance of the start, though the new girl had, touchingly, tried for a few days. Then she started falling asleep in her Cheerios. But he also liked playing knowing she was asleep, pretending he was playing for her, it sharpened his listening to imagine an audience and she was a good critic, this was something he had gained, in the trade he hadn’t asked for. She asked to hear his music, perhaps it was a bullshit interest but the ex-wife had never even pretended to one.

When she heard him start to play, she lifted the Bambino off her chest and found the other one curled alone at the foot of the bed. She stood at the footboard and leaned over and held his rump in her palm — they had not done much touching before, the two of them, but he let her — and she looked at his floppy ears and told him you didn’t deserve that, no one should ever leave you, I won't leave you if given the chance to stay, it might not be up to me. And she found herself weeping, alone there in the dark against The New One’s bed. None of us deserved that, she said, footboard pressing into her stomach, none of us should have been left behind, and she included in this both him and The One Before him whom she had left, and also herself, because before she left The One Before him, she’d been left by many others, and none of them had deserved it. And after that time the other dog became her baby, the moniker landed on him right and easily, she did not even try to swallow it back.

He was writing a new song now. A new album. Up at night in the privacy that would always be his, no matter how married or otherwise domesticated he became, even the dogs were already in bed because he’d put them there. (A child, if he had one, might wail awake with him in the wee hours, but even then only in its first few months or years before it, too, was put down with the woman and the animals, and stayed down.) He was writing about the ex-wife, trying to keep the song uninfected by the woman in his bed. But the chords kept progressing toward the major tonight and finally he let it go. Goose, he whispered when he climbed in beside her, and she usually stirred, reached for the side of his hand or shifted her knee to touch his thigh, subtle movements that would not disturb the dogs. She liked to be touching him. They often wound up in his half of the bed, sometimes she said she was drawing a line down the middle and they had to start meeting there, but she liked touching him too much to wait, whenever she did wait he would get sad about the eight inches between them, would meet her on her side, would say he was sorry, he didn’t mean to put distance, and this would satisfy her for another several weeks of moving to his side.

She was writing a new story now. About the two of them, she didn’t tell him. She understood for the first time why she near-exclusively wrote about love, a fact that had for so long bothered her, she had wanted her brain to be able to hook with equal boundless fascination onto things like politics or ecology or constitutional torts. But now she saw, it was not so much that love fascinated her as that she was moved to write only by experiences that were novel. And love was the one thing that was endlessly novel, she would never be expert, how could she be, when after all those years with The One before Him and the many before that, suddenly she looks down and finds this creature breathing on her chest.

It was a very rational way to enter a relationship. It was, in other words, an older person’s way to enter a relationship. The ex-wife had called him Loop at the start, French bastardized for wolf, had lunged endlessly toward him with mouth open and canine teeth exposed. But they had been twenty then. Babies. It had faded slow and then all at once. When she said divorce, his first thought was of the album he would write. He sometimes entertained the idea of not inviting the new girl back, not because there was something particularly wrong with her but because perhaps he could find another twenty-year-old barely out of milk teeth. She would cheer in half-on panties from the side of the stage. But then he snuck into bed before dawn, humming the song he was writing with its do-re-mis, and saw the dogs’ teeth gnashing in dreams at her breast.

Or maybe writing love was her way of soothing, of convincing herself on the drug of the details, channeling the fear that he would disinvite her into a form that felt as big and purposeful as the album he thought she couldn't hear.

Goose, he whispered to her as the sun rose and he thought she couldn’t hear, which was his favorite way.

She woke that morning with Philadelphia’s gray dawn through the window and the Bambino’s breath in her mouth and the baby’s fast heart at her feet and The New One’s snoring violent in her ears — that was what had woken her, she realized — and understood with a start that she’d never been happier anywhere.

Still he found it sad that she lacked the playfulness to roll on the rug with the dogs or to come up with a name for him and then assert it, continuously, ridiculously. As he had goose. The ex-wife had run around a lot. Gotten down on the rug and made growling noises at the dogs. She was a cheerleader. Extremely beautiful. Of course therefore she assumed she could get more than him, and did. This one was pretty too, even beautiful at times, but not from certain angles and never with her makeup smeared. I too am getting older, he reminded himself, when in a certain light he caught the wrinkles on her forehead.

In certain lights she caught the thing about him that must have been what seemed unready to her at the start. A certain nervousness about the wrists and elbows. For the most part now it struck her as his boy-self, motherless and rising up to meet her. She tried out “kiddo” for a while, but he questioned it at a vulnerable early moment and after that it didn’t stick. The dogs developed a new habit of nosing the blankets until she let them under, pathetic, opposable-thumb-less, wanting to be with him and her under the sheets. She didn’t like the dogs being in the same layer with the humans when they were naked, but he didn’t mind, said the dogs are naked in front of us, aren't they? In a million years she never thought she’d write a dog story. Daddy, she whispered at him when he came to bed at last, petting the small ears like a father, vaping the way he did even during sex, she both didn’t mind it and would have preferred he not, if she could conjure her perfect life. Let me bake you up a man, her grandmother used to say, so you can bite his head off. He would never meet her grandmother. She would never meet his mother. All dead before the two of them had come into the world. “Daddy,” chaste as it had felt in her throat, was vulgar in her mouth and clearly wrong.

It was true, of course, that “goose” did not quite fit her the way “baby” had. That old pet name was a syrupy love and this one was coming out shellacked. They were falling into it head-first, cleverly, playing word games and fun facts and Scrabble. No long petting sessions on divans in the southern heat. She liked this version of love, felt old enough now even to prefer it, sometimes closed her eyes and sent an urgent prayer of thanks to God for it, and for him, when he came to bed and fitted himself in strange shapes around her and the dogs.

And yet she found it sad to not be someone’s baby. Not to be making him hers. Baby-making, of course, becomes a subject of conversation between a man and woman at their age in new love — they had discussed it from the second date, were planning on it, if they made it that far then it was in the cards for them — but not baby-making in the nomenclature sense that had already passed them by. They used each other’s first names even in the intimacy of the bed, where such public names became as strange as the fear of a wet nose to the clitoris. Even in the forehead-to-forehead deep kissing face-to-face sex that they found they preferred. (Missionary, they admitted, was its starting point, but what a glorious mission it felt like when it was the two of them, her legs gradually rising up to the headboard behind them, the only talk they ever wound up with fill me up, finish inside me, yes, they could laugh about it, they were intending to make babies.) He would kick the dogs out when it was time for sex and the maws came growling at the space between their lips, jealous, wanting to be where the heat was. Neither ever admitted aloud to missing them, to half-listening, during the tip into orgasm, for the two small creatures protesting outside the door.

The One Before Him had had dogs too. In an inversion only she (and, she sometimes felt, a God watching amusedly over her shoulder) was aware of, he had been the one to cede the two creatures to his ex-wife and then had missed them terribly, woken up moaning for the weights that weren't on the bed. She had been too dismissive of him, she understood now. If this new one ever declined to invite her back, she would wake up alone to the breath that wasn’t on her chest. My Bambino, she would moan. My baby.

The problem was that he came with two extras to love — three if you counted the city he tried to sell her on and she fell unexpectedly in love with, too easily in a way, he had wanted a harder fight — and she was just herself. No animals, no city. He told himself this should have been a problem for her, but it wound up a problem for him. She loved so many orbital things around him. He loved her. His pet name for her had come first and easily and stuck to her without issue. Hers for him orbited around him but never landed. He noticed.

Irish potato, she tried. Counselor. Good egg. God egg. Nothing stuck. She distracted from it by playing word games. What’s the difference between instinctive and instinctual? Purposely and purposefully? Cease and desist? They debated the distinctions on long walks through Philadelphia with the dogs, looked up the definitions and OED etymologies, both felt their side had been vindicated. He was a lawyer, she a writer. She had bylines in the New York Times but he always beat her in Scrabble.

No, she wasn’t fully living in her own life anymore. Yes, she noticed that the story she called fiction charted shamelessly the trajectory of their real lives. The job of the writer is to do the imaging for the reader, she told her students, straight-faced with hypocrisy, before she burned out and couldn’t remember their names even fourteen weeks in and still got decent evals and moved into his bed officially and quit the job. It is too much work for the reader to imagine the what of things, she said to her final class. Leave to them the how does it make them feel.

No, he wasn’t working on the divorce album. Yes, he was happy she quit and moved up here. But on their first trip to the dog park from a shared address, the ex-wife and the one she called The One Before Him buzzed in their respective pockets. She termed it spooky action at a distance. He termed it quantum entanglement. Not with each other, they were careful to say: it was the way the exes phoned at the moment she leashed the dogs on her own, as if across great distances, they knew. Stepmom, he called her. Adoptive mom, she said. Mama, he said, and it adhered like a hair.

Postcoitally that night they populated Gods and Services, their invented storefront, which sold idolatry and flavored oils. He wiped the residue of their sex from her legs. Idol merchant, she tried. Slid right off. Disastrous, sterile. She shrugged, kissed the evidence of their sex off his fingertips, penciled the two-letter words on flashcards while he decamped to write his album. Studied them in the glow of her cell phone with the Bambino on her lap while the baby moaned low at his study door. Felt The One Before Him buzzing at her thigh.

He was recording a conversation from the dog park. It’s electron spin, an old hound’s dad had volunteered. Quantum entanglement. Where do they go on the other side of the nucleus? Across the room?

You’re not getting it, he’d said. She means paired electrons. One shifts its direction across the planet and the other feels it.

In his new song, when she goes away from him again for the first time, he calls her each time she sits down to a meal with someone else. Spooky, he says.

The One Before Him still loves her. Has not disentangled. Now as she is trying to memorize Greek letternames he is deploying their old pet names for her in a voice message, baby beany bean, and this makes her feel sad, for him or for herself she isn’t sure. When the sound of his voice calling her baby makes her too sad, she feels the dogs’ chins just below her navel under the sheet and reminds herself that he did not actually want babies and so, with him, the verbal tic was the farthest it was ever going to get.

He sees the endearments on her cellphone on the nightstand when he returns and worries suddenly that she is going to leave him. She left The One Before Him, as his ex-wife left him, and when tonight he stands above the bed and asks her why, she says, I fell out of it. I only love him enough now to feel guilty. She doesn’t even remark it when he meets her on her side of the bed. He can’t get his worries to heel. He strokes her hair and can’t find the dogs and it must be hours. The birds are calling. Then from the quiet of what he’d assumed was her sleeping, she says, He was the choice of a broken person. You’re the choice of a healed person. That’s why I’m not going to leave you.

She doesn’t say what healed her.

The dogs curl low across her stomach to her hips. The end of the story might be the loss of all this, she knows. Those little warm fast heartbeats, breathing. When she first fell in love with the dogs she told him she was afraid, because what would it be like to be in love with them now and never see them again? But it was too late by the time she was asking the question, already she had incurred that risk without ever having chosen to take it. But she doesn’t want to include that ending here. No, let it end before the loss of all this, let it end while she still has that heartbeat at her hips. Yes, give her that much, this time. Let the reader do the work of losing it themselves.

Gods and services, he will call the new album he’s been writing all along, atop the phantom album he will never finish. He heard her in her last class: writing is work. It is labor. We labor to bring out these people, these worlds we tell ourselves we wouldn’t write in a million years. It is not for everyone. Your mind like a garden hoe in winter, smacking what doesn’t want to give. He shifts minutely against her stomach to find the vape, and she gives a little yelp of protest. He nibbles her shoulder. I’m not going to leave you, he means, and he knows she may receive it in the general but he means it in the specific. He will not leave again to close the album out. Not tonight. Yes, he tells himself, only in the specific.

What she says in answer sounds so foreign to him that it may as well be French. The tutoyer, vous to tu, formal to informal. Eventually someday it might be second nature, maybe someday it will, but this first time as she brings her lips to his ear and lifts the quilt, it is unavoidably noticeable. My baby, she says, and the sun is rising and the dogs are there and a plume of watermelon-smelling smoke is leaving his mouth. My baby. The dogs are nuzzling her stomach and he’s not sure what she’s telling him. The one she calls Bambino has taken only in the last week to destroying her underwear. Finish inside me, they’ve been saying, from the start. New gods, he’s written in the new album, new services. Do re me fa so, he’s sung at night, all the stupid major-chord two-letter words, Do-me, Me-so, they’ve come to curse at each other, four-letter words. And here she is now, with a pair of snapped elastic in her hand, saying it over and over again against his ear, as if willing it to stick, her sharp teeth chomping at his cartilage: my baby, baby, baby.

In much the same way, as an act of love, she will leave the ending she has already written off the story.

Courtney Sender runs The Craft Lab for Writers Substack, writers’ group, & podcast. She has published in the New York Times, The Atlantic, iHeartMedia, Ploughshares, etc. Her first book, In Other Lifetimes All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me, is out now.

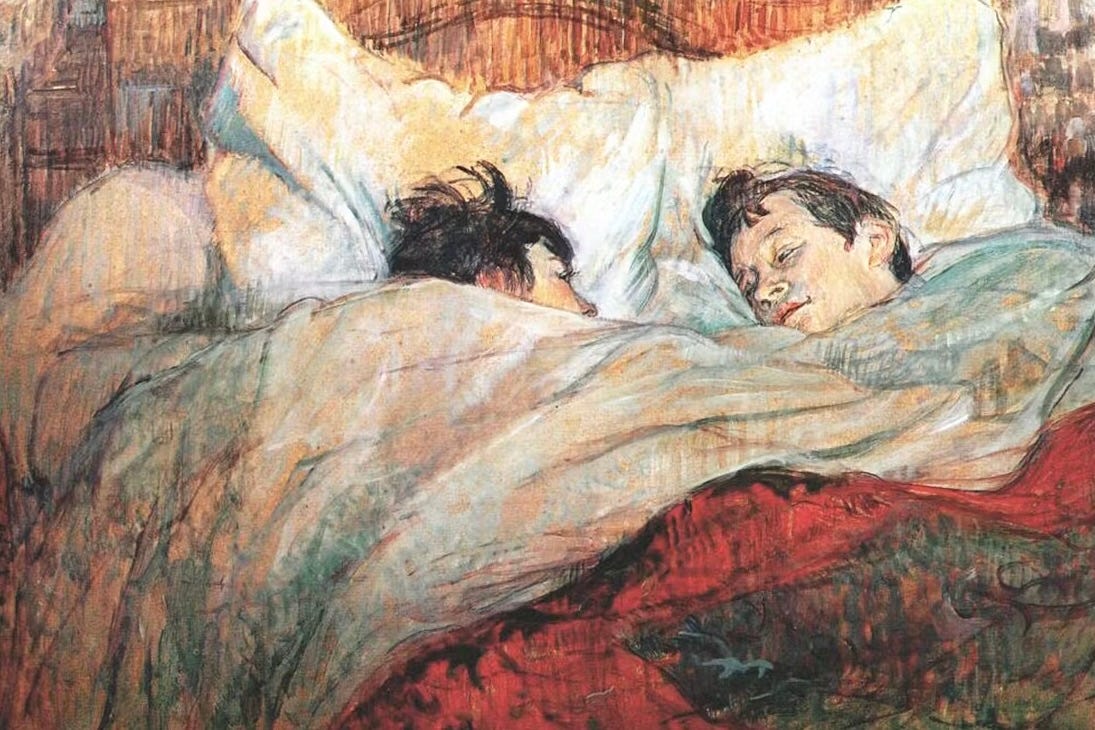

I read this story on my phone before work and thought it was remarkable and then, embarrassingly, only hours later realized, "Oh and they HAVE pets," that the pet-name title has a very obvious double-meaning that just went completely over my head because of the amazingly *nested* feeling in this whole story. There's the kernal of the pet name issue, and of the characters' relationship, that then gets wrapped in some details of their respective romantic pasts, and then we come back to the kernal issue, which is expanded/made complicated by the pets, and then we get wrapped in the details of how these pets (or their avatars) factored into earlier relationships, those questions of safety/nurturing/etc.

There's this imagery over and over of the two lovers wrapped and snug in bed together with the dogs and there's something about the way the story's constructed that...it kinda mirrors that? Like the way the issue at the center keeps getting wrapped up in all these other details, other anecdotes, earlier loves--they're all about affection, and holding, and bonding. This is the only thing I've ever read that seems to EXIST under blankets.

I once found a weird gray block at a thrift store, it was $1, so I scanned it with Google Lens and it turned out to be like a $400 Lenovo charging dock. I picked it up and walked it to the register feeling like a criminal. Bought it for $1. Walked out and got to my car and didn't quite believe I was holding it.

That's kinda the feeling I have about this story. Like I just popped into my local hangout and found a legitimately capital-G great short story. But I don't wanna draw attention to my own enthusiasm?

I've been thinking about this on and off for the 20ish hours since I read it.

This felt to me like a river of voice: thought, memory, desire, humor, fear—moving fast, almost faster than you can keep track of it, and somehow never losing its footing.

What I admire most is how unforced the language feels. This is the kind of voice-driven fiction that can so easily tip into contrivance, and here it just doesn’t.

There’s a real ease to the way it unfolds. It’s confident without being showy, intimate without trying to charm. Nothing stops to explain itself or translate what it’s doing for the reader. The prose trusts its own momentum, and you can feel that trust as a reader.

And it just swept me up.

And the ending, I love it. It doesn’t resolve or explain. It stops while everything is still happening: words still being said, dogs still breathing, the present still fragile and alive. The story refuses to step back and turn the moment into something finished.

We aren’t spared the knowledge that loss is coming—we’re spared having to watch it happen. The story stops short, and suddenly the weight shifts. We carry the rest.

The ending isn’t avoiding pain. It’s holding onto the conditions that made the writing possible in the first place.

Some stories don’t end because they’re finished. They end because that’s as much tenderness as the moment can bear.