What can an image tell us? The celebrated author André Aciman invites us to ruminate on a photograph his late father took nearly a century ago. Though he was a man who kept very few secrets from his son, he nevertheless hesitated to say anything when asked about the photograph. “It belongs to the past,” he insisted. Aciman, though, was not satisfied, and sensed the picture was important. A master of irrealis moods — that realm of might-have-beens and what-ifs — he understood the possibility for more. He has his ideas, his own theories. What do you see? What truth hides in the photograph?

—The Editors

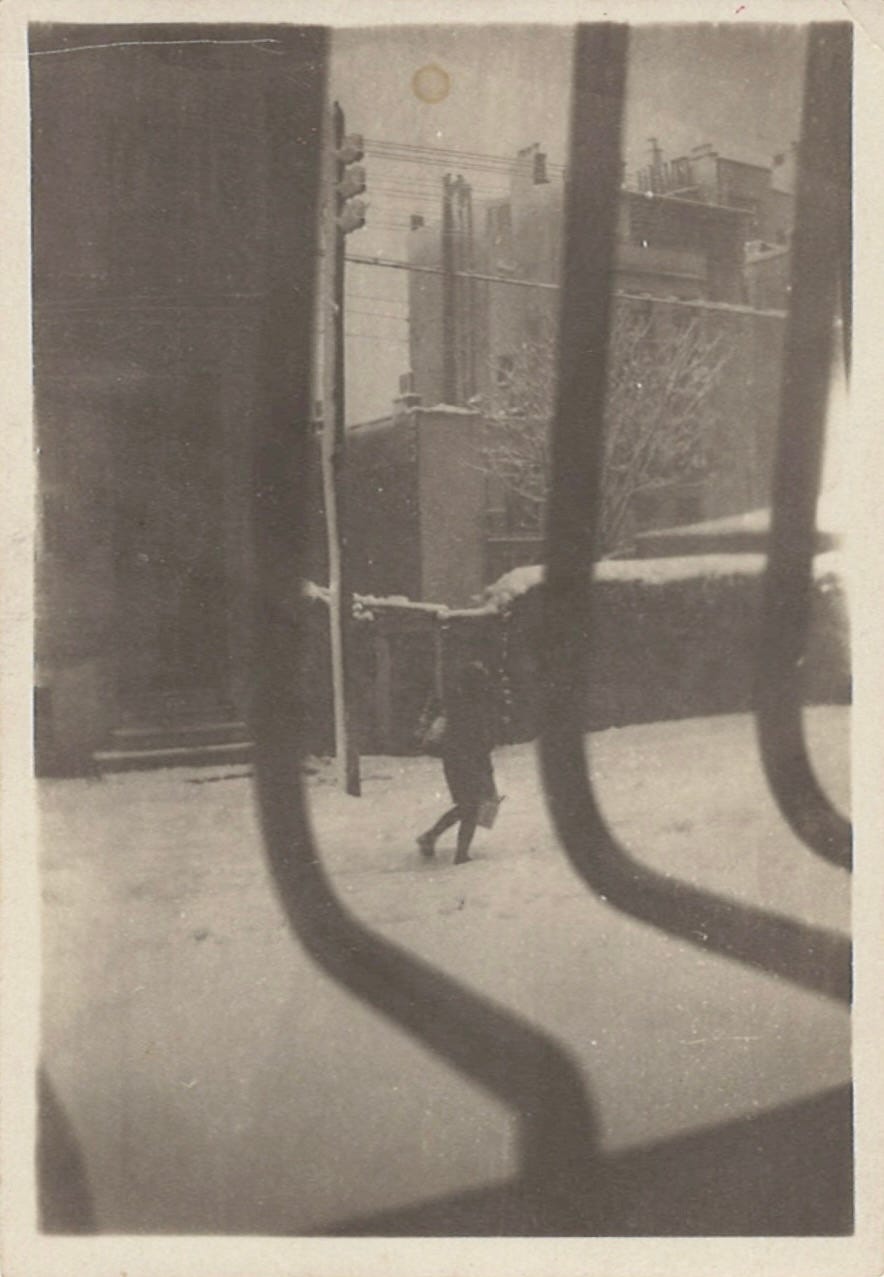

The picture before me was taken from an unknown building looking out on an unknown street. The one bare tree visible from across the street is touched by recent snowfall, as is the large electric pole with its wires stretching high above ground. My father must have taken this photo at the very latest in 1932, which is when he left his homeland never to return. A few weeks before his death in New York, as we were leafing through old photographs, I asked him why he had taken that picture from the sunken basement window that peered out on the street. He gave a hasty look at the picture, recognized it right away, but wouldn’t say what it represented or why he had snapped that photograph. I asked him for the name of the street, which would allow me to google it and show him the same spot on my laptop in today’s world. But his tired reply was, “What for?” He was shutting a door to his past life. No need to share anything any longer. Whatever this was had best be left alone.

Now that I think of it, his behavior reminded me of my great-aunt Elsa, his aunt, who walked into the living room one day brandishing an ancient, frayed magazine to exhibit the full-page, color image of a handsome man’s face, probably an actor or a singer dating back to the early 1920s. She had kept that picture for decades, she said. When I asked her whose photo it was, she knew the answer but would not reveal it and never told me, though it was clear she had once worshipped this man and most likely a part of her still did. Then, having shared the picture with everyone in the room, she slipped it back in between the worn pages of her magazine and returned it to a hideaway where she kept everything under lock and key. Even after she died in the early ’70s, I never found the picture and will never know whose picture it was.

Nor did my father tell me any more about his own picture. All he said, when I pressed him one last time, was, “It belongs to the past.” His silence reminded me of his aunt’s. There was something louche in how both refused to reveal the meaning of each picture. It suggested something more about these pictures, which is what brought me to write these pages. I want to know what I can’t know.

My father died 15 years ago and, because I’ve been rearranging photos — or rather pruning many — the photo suddenly resurfaced, and with it rose the same question I’d asked him 15 years earlier: What about this picture?

Why the secret, what did it hide, what could it mean, even if I was never going to resolve its mystery? What did it want to tell me that my father wouldn’t say?

My father was not the kind of man who kept secrets from me. He frequently confided relationships that most fathers wouldn’t tell their sons about. He told me about the many married and single women in his life, women among whom my mother played a very small part, though she remained his wife for the remainder of his life. As he used to say, she was his wife, true, but she was never his lover. But when it came to the picture in my hands now, not a word.

Why the mystery?

The first explanation is easy enough. On that late afternoon we spent rifling through old photo albums barely a few weeks before his death, my father was taking light doses of morphine, and maybe the picture had lost its meaning for him, or, equally possible, he didn’t want to show that something was tampering with his memory, which induced him to give the photo a murky meaning it might never have had. Or the photo might just as easily have acquired a new meaning, so that he was seeing things that had not been there when the picture was taken. Or maybe the picture was a meaningless occurrence in his life and meant nothing, and because he still retained a mischievous side to him, he liked to suggest mystery when none existed.

But still, he had kept the picture, so it must have meant something to him, and unlike so many images taken at the time, it had no companion photos to help me locate it; it sits alone and is the only picture of its kind in my father’s album. His very reaction on seeing it told me that he instantly recognized something that took him back decades and still stirred his memory. He was moved. It meant something.

I look at the picture now and see that it had snowed that day, and though there are some footmarks on the street, the lady, probably young, who appears in the photo seems to be the only one on the scene. She is walking at a rather slow pace, most likely because she is carrying a handbag and a shopping bag and probably can’t walk any faster, but she doesn’t look burdened or harried by the weight. There is a dreamy if not resigned pace to her walk. Who is she? Where is she headed? Is she a servant girl or a woman who’s gone out to shop? Or has she purchased other things, and a walk in the snow didn’t trouble her and maybe she liked the brisk weather that day? Maybe it’s not a woman but a man. I cannot tell anything. I don’t even know if the photo was taken in the morning or early evening.

Is she someone he knows, someone he’d like to know and has been trailing, following, maybe stalking? Or did she just happen to be in the picture when all he wanted was to capture the street and had caught her blocking the view as she headed along the drift of snow? She’d be older than 100 years now, so chances are she’s no longer alive, the way he’s no longer alive, but the picture, which is still very much alive now, says differently. She is still traipsing along, with two bags, and might still be of interest to him, unless she’s a mere someone who slipped into the picture, and he is still a 17-year-old who might, but then might not, have a crush. Who is she? I’ll never know.

Did my father take the picture because he was surprised by the beauty of the day and, sensing he was about to leave and never return, wished to capture his city as it looked most peaceful and serene under the spell of snow, knowing he was either too glad to put it behind him or that he’d miss it for the remainder of his days? Did he perhaps take the picture on his last day there?

What kind of camera did he own? Did he or his family even own a camera? I’ve seen several pictures of his family, so a camera might have been available.

Nor do I know why he chose to take the picture from what looks like a basement or a ground floor. I don’t recall my father ever telling me that he had lived in the basement of his building. His family would not have lived on the ground floor and certainly not in the basement.

Unless, of course, I am totally wrong, and the scene that my father wished to capture did not lie outside the window but reflected the basement or the ground floor. Yet not finding anything worth photographing or remembering there, he decided to turn his gaze outside, taking a picture of the bars around the window. The bars, in fact, are the loudest and most prominent image in the picture, not the woman traipsing along the street, not the electric pole with its complex wiring, not the tree, not the absent cars, not even the few footmarks on the snow. The bars suggest prison. My father might have been taking the picture of the world outside, but the bars are the most clamorous image he captured.

Was this the image of someone shouting that he was in jail?

Do things still have a life when we don’t know their meaning, their purpose, their essence?

All I can do is speculate.

I like speculating. Because I don’t like answers, I prefer possibilities, things that could be, not things that are. Speculation says something about me more than it says about the picture, about the snow, or about my father and his aunt. It tells me that I don’t like hard answers, and that I’ll take questioning over facts, slants instead of certainties, tangents more than truths, because I like to look at things askance and see other than what’s given to me to see. I like to speculate and see what’s not quite there, as if some other organ or some other dimension were waiting in the wings but didn’t dare intrude quite yet.

And then comes the last speculation among so many yet to come. What if my father had never taken that picture, what if it were given to him as a keepsake, as a token, as a gift, what if so many other things I’ve been unable to conjure but are staring at me as possibilities I’m simply failing to see. What if?

André Aciman was born in Alexandria, Egypt and is an American memoirist, essayist, novelist, and scholar. He is the New York Times bestselling author of Call Me by Your Name and Find Me as well as Out of Egypt. His new memoir, My Roman Year, was released in October 2024, and his three novellas titled Room on the Sea were published in June 2025. He is at work on his new novel.

I will never know what that picture represented. He balked when I asked him, which meant there was something in that picture that he would rather have kept secret. But I'll never know.

No problem at all. But I am flattered that you made the connection.