Before TikTok crowned legions of influencers, taste was ruled by a singular aristocracy: the magazine editors. In his debut book, Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America, author and New York Times media correspondent Michael Grynbaum pleads the case for cultural gatekeeping in an era of algorithmic overwhelm and creative chaos. And what gatekeeper has wielded greater influence over the collective consciousness than the media conglomerate Condé Nast, which once, as Grynbaum reminds us, “had a foothold in nearly every sphere and phase of American life”?

Grynbaum artfully traces the 116-year life of this literary reign: founder Condé Montrose Nast’s conception of the glossy magazine as a symbol of subscribers’ status in the early 1900s, Samuel Irving “Si” Newhouse’s expansion of the Condé brand into a global institution in the century’s latter half, and, finally, its dying breaths in the digital age. More than a publisher, Condé Nast was a mirror — it both shaped and reflected the evolving American psyche, capturing our collective id across the century.

Now, as the hour of Condé’s death seems near, Grynbaum laments what we’ve lost — the unity that curation once brought, now lost in the digital age. In this brave new world of information overwhelm, he argues, we need gatekeepers like Condé Nast to distill what’s important.

This point is compelling, but after reading a book contemplating over a century of Condé’s elitist excesses, one wonders if the proper attitude is to decline the urge to preserve the past.

Why save a dying relic if there’s another way? Isn’t it possible to celebrate the democratization of creativity that social media has granted us while also reinstilling a reverence for Condé’s craft? At its best, Condé created a haven for the flourishing of artistic excellence.

We can’t return to closed-door elitism. But we can’t accept the new normal either — this algorithmic churn, where visibility passes for value and taste is flattened into oblivion. We should embrace the future’s high intentions but learn, too, from the memories of Condé in the twilight of its reign.

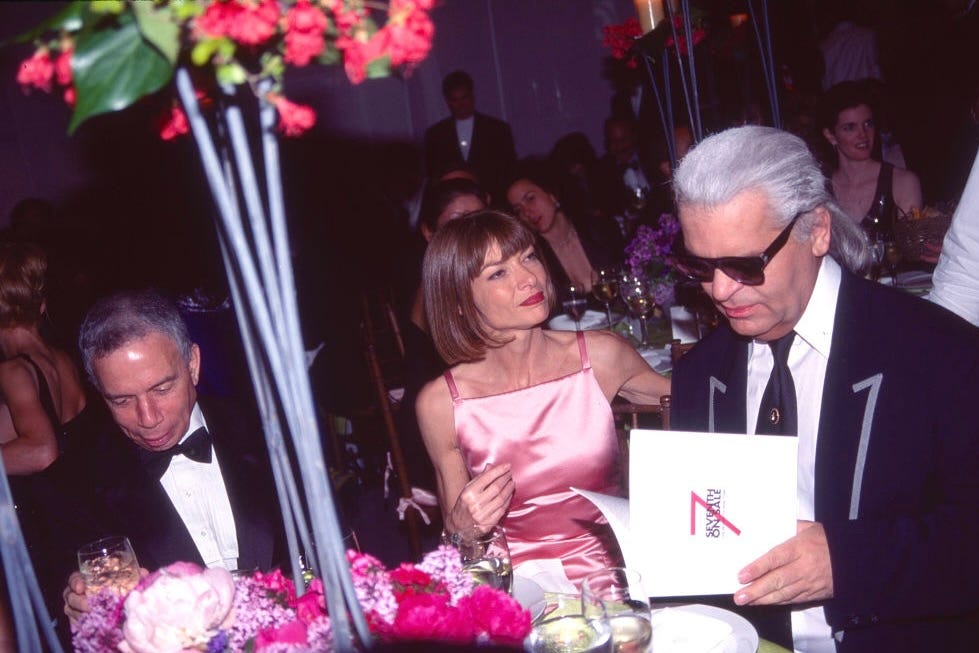

And what a complex reign it was. With The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Vogue, and GQ in a publishing stable helmed by aristocratic editors including Graydon Carter, Anna Wintour, and Tina Brown, Condé Nast’s history is unsurprisingly as rich as the vision of American life it sold.

Grynbaum reveals the intensity of Condé’s The Devil Wears Prada-like work environment. One must dress their best: staffers recall that their daily office wear was what a normal person might wear on their most glamorous night of the year. When Vera Wang showed up to her first day as an assistant at Vogue in a white Yves Saint Laurent dress, she was told to “go home and change, Dearie, because you’re going to be on the ground here crawling around” — that is, on the floor of the fashion closet.

When, in 1994, Si Newhouse found himself choosing a new editor-in-chief, he selected a man of questionable qualification because, after all, men prefer dealing with other men. “Is that very sexist, what I’m saying?” Newhouse asked. (And how does one fire an employee Condé-style? A former editor advises “gutting” them quickly. Then, ask them to lunch, that way they won’t act unbecomingly, thinking they might still get something from you.)

And of course, Grynbaum meditates on the glamour of it all. It wasn’t only that Condé Nast threw the flashiest parties in Hollywood — including the Vanity Fair Oscar Party and the Met Gala — but the grandeur inside the office, where “perks were legion.” Editors had $40,000 yearly clothing allowances, which was considered, by the standards of the office, a modest sum. Condé granted multimillion-dollar mortgages to some of its artistic talent so they could live lavishly in Manhattan townhomes, even occasionally forgiving the loans. One Vanity Fair editor, on assignment in London, lived in the Dorchester Hotel with her family for a month, with Condé footing the bill for a separate room for their full-time nanny.

“I believe money should be used to facilitate a creative life and eliminate fatigue,” editor Alexander Liberman once said. That’s perhaps why the photographer Annie Leibovitz ran up a $475,000 bill for a Hollywood Issue shoot. In her defense, it was stated that, well, “ . . . it looks like a $475,000 cover.” When writer Ann Patchett expensed a turtle for sale at an outdoor market in the Amazon, her editor, William Sertl, approved it, saying there was a policy permitting writers to buy any animal “that rhymes with the name of their editor.”

Such excess wasn’t accidental; glamour was the point. Image was everything at Condé Nast — its editors were the aristocratic arbiters of American taste. Si Newhouse “buil[t] his empire on the mantra that perception was everything.” Americans kept the magazines on their coffee tables to signal allegiance to a “higher cultural plane.” Even celebrities understood Condé’s role. Grynbaum describes a scene in which an editor ran into a famous actress in the Hamptons and saw her boarding the Jitney, the city-bound bus. The actress then promptly left a message with the editor’s office, embarrassedly explaining that she had only taken the Jitney because her Bentley was in the garage.

But Grynbaum doesn’t merely relay a history of empire. He also captures the evolution of American consciousness — its wants, its needs, its deepest desires.

Condé Nast didn’t just tell us what to want. We told Condé what we wished to see; it was the mirror of the American psyche.

In 1984, to be elite was to be athletic and self-made. Americans were aspiring to the Gordon Gekko ideal: greed was good. Condé put a grinning Donald Trump on the cover of GQ with the coverline: “Success[:] How Sweet It Is.” The decadent excesses of 1980s magazines foreshadowed a coarser cultural turn: Americans became increasingly obsessed with celebrity, fashion, and sex. Accordingly, Anna Wintour decided to place Madonna on the cover of Vogue in 1989, a choice seen as vulgar at the time. When Demi Moore, pregnant and naked, made the 1991 cover of Vanity Fair, it was considered by Grynbaum to be “a riposte to an emerging 1990s pop culture awash in sex, but uncomfortable with its potential consequences.”

Following the Great Recession of 2008 and the bailout of Wall Street’s wealthiest, attitudes shifted. That carefree capitalism, which once buoyed Condé’s fortunes, stirred American unease and skepticism. As income inequality has increased, so has the distrust of Condé Nast as an institution. The music hasn’t stopped, but it’s badly out of tune.

Yet it was the digital age that truly sounded the death knell. In 1999, Anna Wintour experimented with a Vogue website. Grynbaum notes that, “ironically, her efforts, forward looking and well intentioned as they were, sowed the seeds of the digital fashion revolution that decades later would leave her and her magazine struggling for relevance.”

Enter the era of lavish Instagram house tours and TikTok wealth porn, an overwhelming cacophony of sights and sounds, American consciousness fragmented into a million small shards. With each social media feed finely tailored to one’s own mental landscape, is there even a collective psyche to mirror anymore? Are one billion disparate TikTok algorithms a sound replacement for Anna Wintour’s discerning eye?

Grynbaum’s writing remains cool and controlled throughout and, at moments, devastatingly funny. On Condé Nast’s 2022 withdrawal from its Russian operation when Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, Grynbaum quips that “even Vogue could not art-direct its way out of that one.” He strikes a delicate balance: showing clear reverence for Condé Nast as a cultural institution while exposing its most unflattering truths. Yet he also misses an opportunity to explore the deeper marriage between Condé Nast and the American psyche. The book, while rich in anecdote and observation, only topically assesses the psychological and spiritual dimensions of the brand’s influence. It’s tempting to excuse this in the name of historical objectivity — but that defense falters given that Grynbaum threads his advocacy for cultural gatekeeping throughout the narrative.

Grynbaum leaves the reader wondering: Might a literary paradise be found again? “For all its faults, Condé brought discernment to the culture . . . a casualty is curation, at a moment where it is desperately needed. The firehose of digital information has yielded a siloed culture that feels incredibly flattened and incoherent.” Social media has, in theory, creatively liberated us. But we are adrift — suspicious, fragmented, alone.

Who will again remind us of the universality of our human longings?

To Grynbaum, the answer lies in reviving dying media institutions: we need gatekeepers like Condé Nast to restore coherence to a culture that has lost its frame. Perhaps the populist political surges of today signal a deeper desire: for someone, anyone, to make sense of it all. To curate not just taste but truth.

And yet — do we truly long for a world so orderly that it dictates whose art matters?

Condé Nast, with its pantheon of aesthetic aristocrats, once made sense of the world. Under its reign, Americans agreed, if only for a time, on what was beautiful, desirable, worth wanting. This authority wasn’t arbitrary. It was earned through the talent it housed: writers like Adam Gopnik and James Baldwin, photographers like Annie Leibovitz and Irving Penn, visionaries like Anna Wintour and David Remnick. These gatekeepers cultivated and strove for artistic excellence.

How, then, do we revive that craft without shutting out emerging talent — those without access to the inner sanctum of Manhattan’s elite? How do we stitch together a culture that honors both refinement and plurality — one that anoints taste without silencing the outsider?

The emerging talent posting TikToks of her paintings from a garage in Ohio deserves as much room in the pantheon as the Vogue editor in her Fifth Avenue suite. Some of today’s voices — like editor Willa Bennett at Cosmopolitan and Seventeen and the late Off-White designer Virgil Abloh — have intuited this. Somewhere between the chaos of the feed and the tyranny of consensus is a new kind of curator. Condé Nast wasn’t perfect, but its authority was earned — an aesthetic obsession with excellence, a belief that beauty could create a kind of higher order.

We shouldn’t romanticize exclusivity for its own sake. But we shouldn’t discard the discipline of craft either. The institution that sees the Vogue publisher thumbing proofs on West 43rd and the Instagram artist mixing mediums in the rural Midwest as part of the same creative cloth — that’s the one we need. The editors who honor excellence without shutting the gate.

Who — or what — will pick up the pieces and hold the mirror?

Savannah (Sav) Huitema is a writer, fashion model, and associate at Quinn Emanuel. She lives in Manhattan.

When Granta chose the Best American Writers under 40 in 1996, Anna Wintour and Vogue co-hosted a party to fete us in Chicago. I was wearing a $250 suit when I met Wintour. I was so intimidated. I was just a rube with a gift for nouns and verbs. Never felt more Gatsby in my life and made sure to stay away from swimming pools.

I once had a meeting with Anna Wintour about a charity event (not the Met Gala!) and was very nervous about what to wear. I played it safe with a dark suit, white shirt, and blue (not sure if it was "cerulean") tie.

You do a great job exploring the tension between the elite and exclusionary curation of the past and the chaotic openness of today.

At the moment I'm most worried about common ethical norms. There is no more "polite society." Perhaps the polite societies of the past were mirages and based on hypocritical perceptions but they existed. If everything is permitted of our modern day elite––the famously rich and the famously famous––then the cost to our society is enormous.

This is where your insight as to Condé Nast being a mirror comes in to play.

Finally, I loved the turtle quip!