An Alexander Sorondo feature is an extravaganza. When we started The Metropolitan Review, we didn’t exactly have Sorondo in mind, but it was very clear early on that he’s exactly the type of writer we want to embolden. Last time you caught the young novelist and essayist in these pages, he was exploring — in more than 10,000 words of riveting prose, the epic life of William T. Vollmann, an American literary master unlike any other. “The Last Contract” quickly set the internet on fire and established Sorondo as a rising star. Today, Sorondo is back — and he’s got nigh on 15,000 words about the author Mark Z. Danielewski’s bid to publish a sprawling series equal to his idiosyncratic ambitions. This being Sorondo, he doesn’t stop there. He’s here to tell you about the history of prestige TV, the Nobel Prize winner Pearl S. Buck, and an enigmatic Polish filmmaker who mentored Martin Sheen, battled Nazis, and happened to be Danielewski’s father. This is the sort of feature you’ll be thinking about for a long time.

The goal of The Metropolitan Review is nothing short of the reinvigoration of literary culture. If you believe in our vision and want to own our limited edition inaugural print issue, please pledge $80 today. That’s the only way to get the print, and you’ll help make our magic happen.

—The Editors

Mark Z. Danielewski started outlining his third novel in 2006 and these were its major characteristics:

The novel would be 27 volumes long (the number is important).

Each volume would have 880 pages (also important).

By releasing roughly two volumes a year, for a dozen years, it would serialize the story of nine central characters converging in Los Angeles around a few central mysteries.

It’d be sprawling and brainy and challenging like his first two novels except this time he’d be doubling down on narrative. He wanted to make something propulsive. Almost addictive. Like a TV series! The sort of prestige show that seemed to be blowing up into something of a phenomenon at the time, 2006-08ish.

Remember: The Sopranos, Deadwood, and The Wire were just ending. Lost was becoming a sensation. Dexter, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and True Blood were just debuting. Critics went from calling it a second golden age of television to the golden age. Not because the shows were edgier, sexier, and more cerebral than ever (though they were), but because the discourse about these shows was wider, better, and more accessible than it had ever been. Social media had turned the proverbial “water cooler” into a worldwide well.

But part of what cultivated that social media discourse, and made the late aughties such a hotbed for great TV shows, is that it was also the golden age of DVDs; more specifically the DVD boxed set, which had the democratizing effect of making shows accessible to people who couldn’t afford cable subscriptions, lived in regions where it wasn’t viable, or those whose lives just didn’t grant space for a 10 p.m. adult drama.

If it’s 1998, and you’re kinda broke, and you’d like to see Oz on HBO, the solution is simple: You cannot watch Oz on HBO.

But in 2006, pretty much anyone can just borrow some discs from a friend, or pick them up at the library, or rent them at Blockbuster — which was suddenly a much friendlier place to visit (Blockbuster was) thanks to DVD rental services like Netflix and Redbox, serious competitors that:

Were more convenient than Blockbuster.

Had none of the punitive spirit and bullshit fees by which Blockbuster Video Cosa Nostra’d their way to the top of the rental market for 20 years.

Suddenly there was an arms race, DVDs were everywhere, and it was usually only six months after the season finale that these prestige shows would turn up on your local store shelf, Redbox chute, or Netflix queue.

Same thing with Digital Video Recorders (DVR) like TiVo and ReplayTV, which hit the market in 1999 for some ungodly price, $900 or thereabouts. But by 2006 they were down to roughly half that number, and by the end of the decade nearly 40 percent of households had one.

If the TV-show model was on Danielewski’s mind as early as 2006, he was ahead of the curve.

A strong model for the opportunity Danielewski saw in this burgeoning TV phenomenon might be the story of how Family Guy took off. The cartoon sitcom premiered on Fox in 1999, ran for two seasons, and got canceled in 2000. Then it was revived for a shorter third season in 2001 (allegedly this wasn’t even about giving the show a second chance; the network just had a few leftover episodes that they didn’t want to waste). Then it got canceled again.

And what could be deader than a thing that died twice?

Except that now, with that third season under their belt, Family Guy had a catalog of exactly 50 episodes — which is widely considered the bare minimum number for a sitcom to get cable-network syndication (this is more of a “norm” than a “rule”). Family Guy sold into syndication shortly afterward; in 2003, on April 20 (apropos), the now-canceled show premiered on Cartoon Network’s programming block Adult Swim, where it pulled 2 million viewers per episode; it accrued a cult status from there, which in turn drove people toward the DVD sets.

As USA Today reported in 2004, Family Guy’s renewal for a fourth season at Fox “marks the first time a canceled show has been resurrected based on DVD sales. The first volume [containing Seasons 1 and 2], which sold 1.6 million [units], was last year’s top-selling TV DVD; a second volume [containing Season 3] sold another million copies.” Family Guy has been on the air for 21 years since.

Like the VHS market did for independent film in the early 1990s, the DVD allowed the creators of complex, unconventional, challenging TV a greater opportunity to find their niche audience.

Daneilewski’s third novel would unfold over 12 or 13 years; and if, at first, it seemed like a crazy gamble, well, so had The Wire and Breaking Bad and Mad Men, all of which started with low to moderate ratings for their pilot episodes, but then viewership would spike for the Season 2 premieres because viewers would spread the word through social media (still kind of a novel medium, without much data about how messages moved through it) and their social network would have caught up on the DVDs during the summer: Mad Men jumped from 1 million viewers, in its pilot episode, to nearly 2 million with the Season 2 premiere; The Sopranos from under 4 million viewers to 7 million; and Dexter saw a 67 percent ratings hike between S1 E1 and S2 E1.

From where Danielewski was standing in 2006, it’s pretty remarkable that he saw what was happening and thought, I can take advantage of this moment where people are raving about complex, longform, ambitious storytelling.

It was a good idea, sort of, but it didn’t work out.

Seeing as he almost made a similar decision 20 years prior, to experiment with a literary form that would’ve spoken to the cultural moment, it seems like fate that it should come to fruition now, in 2006, when he was mature enough to tackle some personal material he’d only flirted with in his earlier work.

Not to dwell on his background, Danielewski went to Yale and got his English degree (class of 1988). Harold Bloom was teaching there at the time, long-established by his 1973 book The Anxiety of Influence, about how certain canonical authors are shaped by an eagerness to conceal or break from their greatest influences.

For Danielewski, however, a greater influence than Bloom might’ve been Stuart Moulthrop, whose general composition class he took. Daily Themes. Sort of an entry-level creative writing course in which students could write whatever they wanted. It was a big room and students were grouped together and tutored through their assignments by grad students who reported back to the professor. Moulthrop was a junior lecturer, not one of Danielewski’s tutors, but remembers, almost 40 years later, that his tutor “came to me and showed me some of his work and we both said, ‘This is remarkable.’”

Moulthrop, at the time, was studying new computer-based works of fiction called hypertexts, digital narratives that could branch off in different directions — if that sounds like “choose your own adventure” novels, yeah, some hypertexts (the “lazier” ones?) were written in that vein, but mostly the point of hypertext fiction was that it wasn’t linear. There’d be a page of text on the screen, various words underlined as hyperlinks, and you would click the one you wanted; didn’t matter which word, or in what sequence; the whole point was that, if the author was savvy about it, everyone got a different, randomized, but still-coherent narrative experience (the difference between this and “choose your own adventure” fictions is that linearity is pretty much out the window).

Moulthrop was optimistic about the medium in general (i.e., the fusion of literature and digital space) but cautious about some of the “game-type” fictions that were taking shape. “I was really trying to argue for a more literary application for these technologies.” In fact, he was writing a paper against those game-type fictions at the time, which is what likely prompted him to riff about it during Daily Themes.

At the end of the semester, Moulthrop received what he remembers as a long typewritten note from Danielewski. This would’ve been 1986. Danielewski was spelling out his literary ambitions and asking Moulthrop if he thought it’d be wise to take those goals in a digital direction. To get the jump on what was likely tomorrow’s trend.

“I counseled against it,” Moulthrop says — adding, however, that “if anybody would revolutionize the novel from the inside, it just might be him.”

A less-mentioned detail in US cultural history circa 2006 is the prevalence of “peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing networks,” which was the older millennial’s nifty little euphemism for piracy, a crime that we enjoyed; networks like Napster, LimeWire, and KaZaA were mostly used for sharing music and pornography but you could get premium shows there, too, sometimes within minutes of the actual broadcast (though that often meant they were recorded off someone’s TV with a camera).

This is what happens when communications and culture outpace markets: People are gonna fall in love with stuff, they’re gonna be moved by it — and then they’re gonna share it. There’s less money in owning things than in facilitating their transfer.

Part of this essay’s thesis is that Mark Z. Danielewski was indeed ahead of the curve when he recognized the burgeoning phenomenon of prestige TV, but that the phenomenon as we remember it was not real.

What hindsight and a broader perspective suggest is that TV wasn’t having a revolution so much as it was finding itself at the intersection of five or six other revolutions (in tech, commerce, media, communications, mores, and more).

So this third novel, the way Danielewski was thinking about it, would have the shape of a TV series.

Every five-volume sequence (vols.1-5, 6-10, etc.) would comprise a single “season” of this book-shaped TV show; 27 volumes, therefore, would equate to four seasons of roughly equal length, and then the fifth season would have “a little extra,” as Danielewski liked to say with a smirk. This was common, at the time, with shows of peak popularity like Entourage and Breaking Bad: They’d split their final season into two parts because it scored two years of programming for one season’s effort; it also gave potential newcomers an extra year to catch up, via DVD, so that when the finale was broadcasting, live, the network could boast record-breaking viewership and charge a fortune for ads.

The books themselves would be — as Bret Easton Ellis called them — “beautiful analog objects,” roughly 4 pounds each, floppy bricklike hefts of paper. There’s a different typeface and layout for each of the nine protagonists’ respective sections. Plus (though it took a couple years for this to become apparent), if you put each volume on a shelf sequentially, as they came out every six months, you’d start to see an illustration slowly unfurling across the spines.

The 27-volume novel would be called The Familiar.

As Danielewski loved to say, “It’s about a 12-year-old girl who finds a kitten.”

This is where you have to look backward in order to understand how someone could even entertain the idea of publishing such a project. Danielewski’s career had launched just a few years prior with House of Leaves, an experimental horror novel that proved roughly 27 times more successful than the words “experimental horror novel” usually portend. Asked what he planned to do for his next book, after the first one exploded (House of Leaves is closing in on its 2 millionth copy), Danielewski told his friend Larry McCaffery, “I know I’ll probably never get this chance again,” meaning the bottomless goodwill of a publisher, in this case Pantheon. Pantheon was so happy with the first book’s success that they seemed ready to greenlight what’s referred to, in Hollywood, as “the blank check” project — e.g., Christopher Nolan delivers a billion-dollar hit with The Dark Knight in 2008, and the brass at Warner Bros. takes a powder and says, “OK, we’ll risk $200 million on this Inception thing.”

Danielewski spent the next few years on his second book, Only Revolutions, a hyper-allusive allegorical road novel written in verse.

You really have to earn this “blank check” project.

The gist of that novel is this: It’s 360 pages long, with 360 words to a page, across 36 lines, and after the 18th line, you have to rotate the book 180 degrees to read the bottom 18 lines, written from the perspective of the other one of the book’s two allegorical young-lover narrator. Thus you’re handling the book like a steering wheel. Turning and turning. Hence its themes, too, of cyclicality: in nature, in culture, in history.

I wouldn’t recommend it. But it’s important for the trajectory of Danielewski’s career because it was such a tight canvas, encompassing a library of literary allusion, with such formal constraints that finally — though it became a finalist for the National Book Award — it was such a hermetically demanding project, so exclusive in its complexity, that Danielewski became interested, with this third novel, in writing something for a larger audience. Something recognizable.

If the mid- to late aughties saw a revolution in TV, home video, music and movies (the Marvel Cinematic Universe debuted in 2007), one thing that seemed constant was books. The business of books might have been changing a little bit, with the explosion of e-commerce platforms like eBay and Amazon, and yeah some people were buying e-readers like the Kindle and NOOK; but the literary marketplace wasn’t so visibly different from what it had been just a few years prior.

That’s what made some of these digital revolutions so disruptive — they were invisible.

And that’s how they destroyed the Borders superstore. One of two leading booksellers in America through the 1990s. Second only to Barnes & Noble.

Restlessly so.

Following its acquisition by Kmart in 1992, as a chain of 22 bookstores, Borders defined the decade with a campaign of relentless expansion. New locations in far off places just because they could afford it. Twenty-some stores in London. Another in Singapore. An early gloss over the company’s history suggests you can trace its bankruptcy back to this original Ozymandian sin — but the deeper you go, the more “original sins” you’ll find. Borders arguably instigated its demise back in the 1980s with the introduction of warehouse-size inventories that gave it leverage in negotiating 50 percent wholesale discounts while standard bookstores got 40 percent Then they negotiated even steeper discounts with “special placement” deals; i.e., “If you shave another 5 percent off our wholesale price, we’ll keep this title shelved face-out, at eye-level, so that it’s the first thing people see when they open the door.”

One way Borders was revelatory, in the bookselling market, is they were the first to commodify space. (A Danielewskian development.)

So the retail bookmarket was a bipolar space, with sellers of media on the brink of a media revolution. Both companies saw it and both took action — but whereas Barnes & Noble started shredding their cash in the direction of digital platforms (e-commerce and e-reading devices), Borders decided to look at the customer behavior right in front of them and give those customers what they seemed to want more than anything: CDs and coffee.

Come to Borders and don’t just browse the books — get yourself a drink. A snack. Check out these high-tech kiosks that let you swipe any CD’s barcode under a red light sensor, pick up a chunky pair of black headphones off a black metal peg on the wall, wipe the last person’s sweat off the stiff, plush pads, pull them over your head, and sample new music.

Hang out.

Become a shopper of the new millennium.

Obviously, The Familiar is about more than a little girl who finds a cat. On a rainy day in May 2014, we see that nine characters in different situations across a very vast canvas hear the call of a dying kitten.

Yet they’re spread out across California, Singapore, Mexico, and Texas — it’s not possible they’re all hearing the same tiny voice.

Something paranormal is going on.

The protagonist, a 12-year-old girl named Xanther, is the only one who responds to the crying sound. She jumps out of her step-father’s car, middle of traffic, and rushes through the downpour to rescue the cat from a gutter.

What we learn, with time, is that it’s not really a cat.

Danielewski had the whole series planned, but it wasn’t set in stone.

As he tells readers at his unrelenting tour dates, beginning with The Familiar’s debut in 2015, the ending he has in mind, for Volume 27, will almost certainly look different once he finally sits down to write it, years from now.

Why’s that?

Because, Danielewski said, he too will have been changed along the way.

This was ambitious, geared toward compulsive readability, and Danielewski was probably arguing an increasingly persuasive and prescient-sounding take on the whole TV phenomenon. He’d already written one phenomenal bestseller. Only Revolutions didn’t make much money, but it got some awards attention.

Pantheon decided to take the risk.

They paid him $1 million for the first 10 volumes.

But there was a catch.

If Danielewski wanted to imitate the TV series in the form of a novel, with all of its seriality and structural whatnots, Pantheon’s attitude was, fine, do your thing — but a TV series abides by certain commercial realities too; namely the fact that, if it doesn’t do numbers, it gets canceled.

So this was the plan: Danielewski would submit the first ten volumes (more or less) in advance of Volume 1’s release, and after every five volumes (i.e., every “season”), he and Pantheon would sit down, look at the numbers and ask, Is this thing making money or not?

If not, the series would end where it stood.

Borders took a stab at the internet thing, selling books through Borders.com for a while, but designing an online store in 1998 was a highly specialized task.

The digital infrastructure, the accounting, the tax component . . .

It was complicated enough that eventually, rather than pump unending money and misery into this thing while maintaining its juggernaut brick-and-mortars, Borders gave it two or three years before someone in a C-suite leaned back and said, fuck this, put his feet on his desk and pulled those flexy crab-claw headphones over his ears, somebody call Jeff Bezos.

Throughout my interviews, when people talked about engaging with Mark Danielewski in any kind of professional capacity, you get a glimpse of the chasm they expect to find between intelligence and kindness: They talk about his braiding of these two qualities as though he were a very tall newborn with a wallet.

He is, by all accounts, obsessively punctual. “Mark” will suggest getting together, and you will check your watch thinking, Yeah I got time. He’ll say, Cool, what’re you doing two weeks and eight minutes from now?

His complete and unblinking focus on everything you say in conversation is described as a very gentle violence.

One of his now-retired copyeditors from Pantheon apologizes that there’s not much she can remember about her collaboration with Mark except for his manners, which were downright cordial, and that he’s one of the few writers she ever worked with who demonstrated not just a technical understanding of how copyediting works, but also (from how she describes it) a kind of empathy for its labors. She says he gets it, basically. Which echoes an anecdote (though it varies slightly) about the time he was working on House of Leaves and Random House said they’d have to spend a fortune getting the labyrinth chapter formatted and printed (with its sprawling, inverted, mirrored text). Mark told them to basically sit tight while he learned how to use some page design software himself and then flew out to New York, on his own penniless dime, to work at Random House HQ for several days and lay those pages out on his own, showing up early each morning with an office-quantity of coffee. Good coffee. Fragrant coffee. That way nobody would be bothered. Hey, who’s that punk over there? Eyeballing his computer skills, How come he’s hacking into the mainframe?

He is, by all accounts, monastically disciplined. Attentive to every detail.

A former Pantheon employee, who hints at some relief among the “design team” when The Familiar was canceled, says, “Mark is very . . . ” then thinks for a moment, “particular.”

In 2001, Borders began outsourcing all online sales to Amazon.

If you went to Borders.com, saw a book that you liked, and clicked on it you’d get zapped out to the same book’s listing on Amazon.com.

The partnership seemed to work for everyone: It offered Amazon some status in the world of “high street” retail and Borders kept its customers.

The mistake here seems to have been the belief, on Borders’ end, that those people buying books online were not the same people who’d otherwise be coming into the store.

But there were two exceptionally bad components of Borders outsourcing its e-commerce to Amazon.

First, there was no revenue-share deal; Borders instead got a referral fee for each sale. A book itself would have to be shipped out from Amazon’s own warehouse, meaning the burdens of overhead were all theirs — meanwhile Borders got its tithe just for being there. Resting on its laurels. Carrying the brand.

The second bad component, and the worst, wasn’t that Amazon kept the revenue from each of these Borders-based sales; it was that they kept all the data.

But what was the value of data back then, in the relatively pre-digital world of 2002?

Well, imagine you’re competing with Borders. They sign this deal. Anytime someone tries to buy a book on Borders.com, the whole transaction gets shunted over to your website. This means that, when you look at your metrics, you can isolate the customers who came to your site through Borders.com; i.e., you can study Borders customers en masse when they don’t think anyone’s looking. You can see what they browsed and what they bought. It’s a pretty wide net that won’t mean much at first but over time you’ll see patterns. You can break up the data by age, profession, gender, region . . .

OK. But what can you do with that information?

Well, maybe you notice that, among Borders’ shoppers, men in Boston are among the most reluctant to actually buy something off the site (remember that this is an era when your first purchase off Amazon is also, quite likely, your first-ever purchase off the internet) but they browse a lot. They’re e-curious. And when you look at what they’re browsing you see that they’re 30 percent more likely to buy sports memoirs than anything else. Alright well maybe, just for Boston, you run a buy-one-get-one sale on sports memoirs. You’ll take a hit on the profits, but you’ll have compelled a huge number of people (Borders loyalists!) to take a chance on your website for the first time. The damage you’re doing to your own bottom line is nothing compared to the slow corrosion you’re creating for Borders — which, don’t forget, has zero online commerce capability at this point, meaning their customers cannot buy books while sipping coffee at 6 a.m.

But yours can.

Their customers can’t respond to an emailed coupon with an instant click, can’t browse the shelves at midnight over wine, and can’t instantaneously notify their friends about a flash-sale.

Yours can.

This also means that the warehouses you have in different regions can start stocking up on things that customers in that region are likely to buy from Borders, so that when e-commerce skeptics finally take that leap and place an order with your company, they’ll have a faster than usual experience.

With Borders’ customer data you can play with prices to measure their elasticity across different genres, demos, pagecounts, regions, topics — even times of day. Are people more likely to splurge for a pricey book at noon than they are at 3 p.m.?

You’ll find that out.

This awful deal might be the reason Borders survived as long as it did. For the next seven years they were more useful to Amazon alive than dead.

Another catalyst for The Familiar, such as I could glean from Danielewski’s interviews, is that he figured he probably wouldn’t survive another project like Only Revolutions, a book whose complexity is exhausting to even summarize, so if you imagine a single person building that novel, alone in his late 30s, you might well imagine the croaky-voiced and bearded thing that was its author, circa 2005.

20 years later he still describes the experience of writing Only Revolutions as isolated, a ruiner of (two) relationships; his go-to joke is that, if he’d stayed in the same creative headspace, the next thing he’d have written was a manifesto in a cabin somewhere; clearly a joke but, if you watch some of his select appearances from the Only Revolutions book tour, it seems pretty clear you’re looking at a depressed person.

In one video from the tour, we see Danielewski reading at a chain bookstore and becoming visibly distracted by an opening door. Then someone walks out. Once the door shuts behind the person, he pauses . . . starts to riff. I thought he was enjoying it.

The audience chuckles.

And so Mark banters. He doesn’t jump right back into reading. Seems to actually drift from the task at hand. Like he’s discouraged by the walkout. Doubting himself.

In another video, at another bookstore, the author sits criss-cross applesauce on a table, addressing his audience with an elbow on his knee and chin on his palm. It’s a Q&A. He tells what begins as a funny story about researching the novel, which involved a lonesome road trip through America, and how he maneuvered a yellow Mustang through all types of weather, icy roads and white-out snowstorms, but the stories (well-told!) morph into a series of near-death experiences, his car swerving and swaying with several hundred pounds of sand in the trunk that keeps himself from flying off the road and dying.

And yet: Only Revolutions is a love story! It depicts the kind of yearning, handsy, achingly forthright type of love between teenagers. Yes it’s filled with Finnegans Wake-style wordplay, it’s highly allusive, and he’s using weird archaic slang from the past hundred years, but the novel’s sensibility is completely sincere. For all of its jaded Gen-X sensibility, scoffing even at the idea of “revolutions” (the title can be read in a few ways), the author seems dismissive, even half-contemptuous, of everything on Earth; the two things he never condescends to are his heroes, Sam and Hailey.

Danielewski has said that his two relationships fell apart because he was immersed in writing that novel — and yeah, that makes sense. It’s 360 pages of wordplay and puzzles, a monument to not communicating.

Only Revolutions is a porthole into Mark Danielewski’s nature, as both an artist and person, revealing that the punkish postmodern intellectual we see and hear on book jackets and interviews is actually a lot more like the guy who’s wounded when somebody walks out of his reading.

So Danielewski’s goal with The Familiar, after that hermetic experience with Only Revolutions, was to do something collaborative. Something that took him beyond his office.

He wanted — as the novel is fond of saying — to OPEN THE DOOR.

Borders surrendered all of its e-commerce (and, by extension, its customer data) to Amazon’s Jeff Bezos the same year that Apple’s Steve Jobs climbed a Cupertino stage to give a PowerPoint presentation. The audience was small but rapt. He wore his signature outfit of blue jeans and sneakers, black shirt and malice. The room was lit like a college class as he started his lecture. He paced under a big canvas screen that spelled, in Comic Sans, little commercial flirts like “CD-quality” and “Ultra-thin,” things we’d all like to be, until finally asking:

“What is iPod?”

A small white brickish thing, like a deck of cards, with a Kubrick-white faceplate and a mirrored metal panel in the back. It was quiet and simple. Celestial. Elegant. 6.5 ounces of future.

The iPod, with its black-and-white display, held 5 GB of storage, or roughly 1,000 songs. It had only four buttons. It sprouted long, white, gummy earbuds that quickly doubled as a fashion statement.

The brass at Borders surely saw the coverage. Considering their track record, they probably guessed it was nothing to worry about. Emptied a Zima over their pager and pulled their headphones back on.

But even a hint of prospective danger in the music space should have been cause for worry if not, at the very least, a call to action. Consider:

Total floorspace at an average Borders superstore was 30,000 square feet.

8,500 square feet were devoted to music.

400 square feet were devoted to home video.

1,500 square feet were devoted to cafe space.

And this was their average inventory:

128,000 book SKUs,

50,000 music SKUs,

9,300 video SKUs.

In terms of square footage and inventory, the first-generation iPod — however batshit a $399 price tag might have looked in 2001 (roughly $700 in 2025) — was positioned to attack one of Borders’ largest vulnerabilities.

By the end of that year Apple released two more models, with double and triple the storage capacity, and a cyber-age touch wheel that made it all the more elegant.

The original model went down to $299.

At some point around 2007, Danielewski has dinner with two other novelists, David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Franzen; Wallace, at this point, is teaching at Pomona College in Claremont. He wants Danielewski to join the faculty.

I reached out to Bonnie Nadell, Wallace’s former agent, and asked if Wallace ever spoke to her about this dinner or about Danielewski in general, and she said no, not really. She figures Wallace read House of Leaves, but tells me she can only speak to her handful of personal encounters with Danielewski himself around that period. “He wanted to do this book about cats and I remember talking to him and being like, ‘Huh, that seems a little weird, a little far-fetched,’ and he said, ‘I don’t think Random House wants to do this.’ I said, ‘Yeah, they probably don’t.’”

She remembers just a single semi-professional conversation about it (with the caveat that it’s been 20 years), and that she found the idea “peculiar,” but very much in stride with what she was being tapped to handle at that point in her career. “I did get lots of smart boys saying they wrote a 500-page novel with no punctuation.” They tell her, “‘You did Infinite Jest, so you’ll love this.’”

(Another detail I hear from a few interview subjects is that Danielewski parted from his literary agent, Warren Frazier, around this time. I left a few voicemails at Frazier’s agency but got no response.)

It’s hard to know how far along he was with The Familiar, at this point, or how fleshed out the idea was, but clearly he saw the shape and the scope of it, and was cautious about how to move forward.

Borders Group Inc. announces to shareholders in January 2005 that fiscal year (FY) 2004 was the highest-grossing year in the company’s history.

In January 2007 they report that, for FY 2006, earnings were net-negative.

A few months later, the U.S. is in a recession.

In November 2009, Barnes & Noble debuts its e-reader, the NOOK, for $259. It sells 250,000 units. (Would’ve sold more but they ran out.)

Amazon’s Kindle sells nearly five times that amount.

By the following year, Barnes & Noble will have sold more than 2 million units, occupying roughly 20 percent of the e-reader marketplace — which becomes even more competitive that same summer as Steve Jobs takes to yet another stage, in San Francisco this time, in the usual getup except now his cheeks are hollowed and his forehead bulges. His shoulders jut through his turtleneck like it’s still on a hanger. But he’s the same salesman as ever. Jobs introduces the iPad. It costs $499.

Not to be outdone, Amazon releases the Kindle 3 later that summer. It costs $139.

In 2008, Borders throws in the towel. Puts itself up for sale.

There are no takers.

They close locations by the dozen.

They file for bankruptcy in 2011 and liquidate all stores that same year.

Prowling Reddit you can still find employee anecdotes about the final days, that bi-weekly cascade of storewide sales, 10 percent off goes to 20 percent, then 30 percent, customers asking if this is on sale and being told, yes that one too, unless the employee realizes that they want that book, in which case, unfortunately not. Playing personal music over the store speakers. Dressing empty bookcases with signs for DISCOUNT AIR GUITARS. One disgruntled customer gets in an employee’s face about something, “I’m going to call your corporate office about this,” to which employees laugh.

Borders is gone by the fall.

A major part of what would galvanize The Familiar’s sales is that it was a “beautiful analog object,” something that catches a browser’s eye in a bookstore so that they bring it down from a shelf, fan the pages, and get absorbed in all the moving parts.

Borders dropped from roughly 1,000 locations in 2000 to 399 by 2010. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, this accounted for roughly 4 percent of U.S. bookstores, but more than 40 percent of bookstore market share.

So Danielewski, in 2011, is five years deep in this project that was built, partly, as a thing to be experienced in bookstores, when roughly half of the U.S. bookstore market share vanishes overnight.

The closure of a local Borders Superstore doesn’t mean that all, or most, or even half of its customers will simply switch to the next-nearest retail bookstore.

For most of them, it means switching to their desktop.

One Rainy Day in May comes out on May 12, 2015, and I still have a receipt somewhere confirming I bought it around 9:12 a.m. from an indie bookstore in Coconut Grove that six to 10 weeks later had sheets of brown paper in the window and a landlord’s red letter notice on the door. Here’s what the New York Times had to say: “His crowded and inventive pilot show has me curious about his characters’ futures and how he will connect them. It’s difficult to evaluate a work barely in progress, but I’m definitely in for Volume 2.”

That review was written by a guy named Tom LeClair.

Danielewski heads out on the first phase of a rigorous book tour routine — eight or 10 cities in as many days — similar to what he’ll be undertaking for the foreseeable twelve- or thirteen-year run of the series. Public readings. Q&As. Podcast appearances. Flogging books wherever books are flogged.

This project he’s been living with for the better part of a decade, for which he’s traveled the world and written probably a half-million words, is now free of its cage.

The publisher is invested. The bookstores are stocked. Reviewers are opining. Readers are engaging.

The door is open.

Volume 2, Into the Forest, comes out on October 27, 2015.

A reviewer on NPR marvels at how it is “somehow, remarkably, amazingly, almost impossibly better [than Volume 1].”

The American Book Review said: “I hope Danielewski has . . . plans to eventually fill in the blank conceptual spaces of The Familiar. If not, it could turn out to be more Long Entertainment than Big Book.”

That was also written by a guy named Tom LeClair.

General readers meanwhile are confirming Danielewski’s hoped-for effect: Those who braved their way through Volume 1 (even if it was disorienting) are finding, with Volume 2, that the once-weird format is now more familiar. Easier to read.

People are commenting on social media that they’re finishing Volume 2 in a couple days, as opposed to the couple weeks or months they spent with Volume 1.

In June of 2016, with the release of Volume 3, people will report finishing all 880 pages in one sitting.

In August of 2017, Danielewski is in Manila for the Philippines Readers and Writers Festival. It’s his first time in the country and he does some friendly interviews about The Familiar. He sounds normal enough. Buoyant.

Danielewski would later say, in a 2022 event at San Diego University, that this was the trip where it became clear that The Familiar would not go beyond Volume 5. Whether it’s a phone call or an email that breaks the news, or just the time for reflection, he doesn’t say.

Volume 5, Redwood, comes out in two months, just a couple days shy of Halloween; however, barring some burst in sales for the whole series, Redwood alone isn’t likely to save it.

Danielewski was interviewed that week by the now-defunct CNN Philippines. His interviewer, Aldrin Calimlim, remembers nothing low or grim about the author’s demeanor during their conversation at the Raffles Makati hotel, and the transcript isn’t remarkable except for Danielewski’s answer to the question of a House of Leaves adaptation. “I was recently approached to see if I would be interested in being a showrunner.”

He mentions HBO and AMC.

“Now, for me to do that would mean the end of The Familiar. There’s no way I can continue doing both.”

He stops in Singapore between the festival and his October book tour for Redwood. While there he meets with the author and artist Sonny Liew who confirms, via email, that the two had just met (they’re both published by Pantheon) and that Mark said he was visiting Singapore for research.

But why go back to Singapore for research on The Familiar if he’s just gotten word it’ll be canceled?

Maybe it was already planned. Maybe he took it as a vacation.

What seems more likely is this. There was still a chance (however remote) that Redwood might succeed, and resuscitate the whole series; if that happened, and the twice-a-year publishing cycle resumed, Mark had to be prepared for the next volume.

So he kept at it.

Pantheon canceled The Familiar in 2018 because it wasn’t making money. It was an expensive book to produce and either it wasn’t profitable enough, or it wasn’t profitable at all (likely the latter). According to Circana BookScan U.K., Volume 1 is the only installment to have sold more than 1,000 copies to date. I couldn’t find U.S. numbers but, by a few multiples, they likely saw the same steady decline of roughly 10 percent from one volume to the next.

As Danielewski said in 2022, “By the time we hit the fifth volume the readership had dropped to a point that no one could justify that [production] cost.” Conceived just ahead of a “peak TV” explosion, in 2006, The Familiar wasn’t released until 2015 — almost the exact point at which the era of peak TV was ending; as FX CEO John Landgraf would put it to the Television Critics Association that year, the TV business was “in the late stages of a bubble.”

He speculated that 2015 or 2016 would see the TV market airing 400 scripted shows at the same time. “We’re seeing a desperate scrum. Everyone is trying to jockey for position . . . . We’re playing a game of musical chairs, and they’re starting to take away chairs.”

When thinking about how The Familiar might have moved ahead, here are some things to consider.

While promoting Redwood on KCRW, Danielewski tells Michael Silverblatt that he thinks he can finish the series in 15 years, not 12 or 13.

The cancellation of The Familiar, in February 2018, came before the supply chain delays of Covid, which would have turned a 15-year project into at least a 16-year project.

But who, in the course of their life, goes 16 consecutive years without a serious health issue, a tragedy? All it would take is a delay of some weeks to derail a release cycle.

Maybe in 16 years he won’t experience any health crisis or tragedy, but what about his family?

It feels conservative to estimate that, with just a handful of setbacks, The Familiar would have taken closer to 20 years to complete.

But who could hold onto an attentive readership that long?

Consider the prestige shows this series was emulating: The Wire, Deadwood, Sopranos, Dexter, Six Feet Under, Twin Peaks, True Blood, Game of Thrones — none of them lasted 10 years. Granted, TV is a different market and actors’ salaries have to go up with each season while creatives want to go off and try new things, maybe start families, retire . . .

But would the audience still be there, for any of these shows, after a decade? Audiences were already defecting from The Wire during its lackluster fifth season, and fans of The Sopranos were losing faith after Season 4.

On February 2, 2018, Danielewski posts The Familiar’s logo on his Instagram feed, with a triangular “play” button hovering over its center. In the caption, he writes: “It is with a heavy heart that I must report THE FAMILIAR has been paused. There’s no denying the intense readership that showed up for this endeavor . . . . Unfortunately, I must agree with Pantheon that for now the number of readers is not sufficient to justify the cost of continuing.”

All the complexity of a 10-year project came down to sales.

What I realized, after The Familiar had ended, is that this sort of flat, bloodless, hardstop truth of things, this market reality, is the exact sort of tragedy that Mark Danielewski’s fiction salves; his fiction is a place in which everything means something. He’d probably prefer to say the books don’t have meaning but, rather, help a reader exercise the muscles by which meaning is discovered; here, in the text, as in every place else.

Fine.

But there is meaning, stuff he has put there, as the books’ author: surface, sub-, para-, metatextual significance with which Mark himself has imbued the color-coding of certain words, or the way that the text gets discreetly smaller on a certain page, or the way a CIRCLE appears in the upper corner of a page, like a cigarette burn on a movie reel; it’s a solace akin to what some folks might get from a religious text, one that suggests everything in the world, from the angle of the grass to the breeze in your hair to the landlord’s notice on your door, is one small indispensable quark in some Designer’s larger (beneficent!) plan.

His idea, I think, is that engaging a book like this, one that encourages you to find meaning in every little detail, will train you to look at your life that way.

Redwood

Let’s go back to 2017. Danielewski’s final visit to Bookworm on KCRW. He’s promoting Redwood in conversation with Michael Silverblatt — who loves it. Says he read 880 pages in a day. Says he was so eager for more of The Familiar that he went and peeked at the MZD Forums.

There, he says, he saw readers explaining that the name “Redwood” comes from a long story that Danielewski presented to his father, the filmmaker, on his deathbed.

The famous “cult” director of stage and screen.

These readers are saying that Danielewski wrote the short story “Redwood” for his father, his father read it, and then became enraged, and tore it to shreds.

Laughing then, Silverblatt asks Danielewski where his fans learn all this stuff.

You can hear in his answer the curve of a courteous smile. He says he doesn’t call them “fans” but “readers.” He compliments their ingenuity, their ambition, their creativity.

It’s an effective dodge.

Silverblatt got a detail wrong: Danielewski’s father didn’t tear up that 1992 version of “Redwood.” Instead — as Danielewski puts it — his father “applied all his years of intellectual edge and shredded” the story, verbally.

It was Danielewski, in response, who “did . . . the closest thing to suicide I can think of — I tore up the manuscript of ‘Redwood’ into a hundred pieces, flung them into a dumpster in the alley, and spent he next few days in a kind of emotional coma.”

That was 1992.

Why doesn’t he correct the record with Silverblatt?

Mark told that story about “Redwood” only once, in an interview that he gave twice, to Larry McCaffery and Sinda Gregory.

I was curious why Danielewski would’ve revealed something so personal at the outset of his career, since he was already crafting the buttoned-up persona he’s maintained for a quarter century; he likely figured it was only a matter of time before people made some sort of connection between House of Leaves and his father’s career. The novel, after all, is about a lost film called The Navidson Record; the film, as described in the novel, is lost, but it might not even be real.

Mark Z. Danielewski is the son of a famous filmmaker named Tad Z. Danielewski — a man who also, somewhat famously, made a movie that was lost.

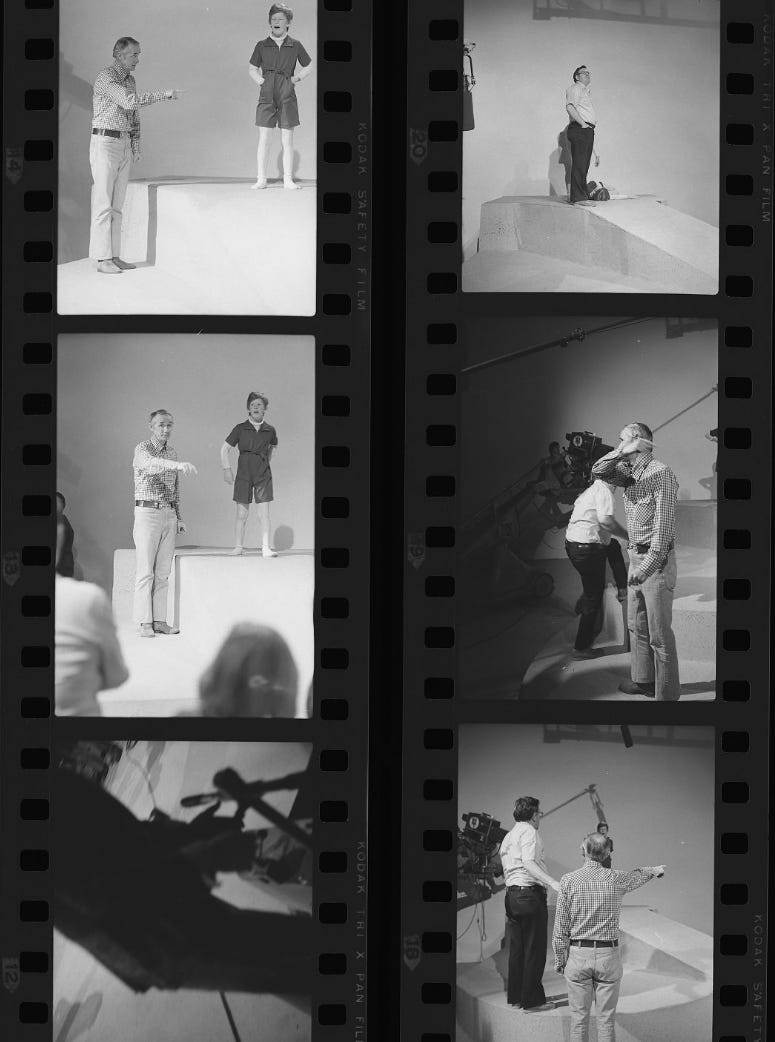

Look up Tad Danielewski online and you’ll find a few photos on Google, some credits on IMDb, and on YouTube you’ll find the abridged Hamlet that he shot for a 1955 episode of the U.S. show Omnibus. If you read Mark’s work, and you know about the troubled relationship with his father, you’ll probably find it interesting that the only readily available clip from this filmmaker’s body of work is from Hamlet, of all possible plays, and so maybe you decide to look into it, run a Google search for “Tad Danielewski + Hamlet,” thinking surely somebody’s seen this clip, picked it apart, and written some analysis comparing the father’s Hamlet with the son’s House. Except what you find instead is a playbill from Tad Z. Danielewski’s 1979 production of Hamlet, at the Pardoe Theatre in Utah, whose players and crew — if you take a little time, look them up, and send an email — are occasionally dead but for the most part quite willing to talk; eager, in fact, with some grinning at you in a Zoom call saying that they haven’t thought about Tad Danielewski in 45 years or that they’ve thought about him daily. Smiles widening as they reminisce. Closing their eyes to remember a detail. Snapping their fingers. Grasping at air.

Impersonations! They do the accent. The way he’d say, “CUT CUT CUT,” even on a stage, without cameras, walking up close to you when he’s got some notes about your performance. Often he won’t even tell you what the problem was. He’s very Socratic, the way he teaches.

Saying, “I WANT YOU TO CONSIDER . . . .”

More like suggestion than direction. His head tilted down and eyes rolled up at you. One interview subject says it sounds condescending, Good boy, but doesn’t feel that way. How he talks you into reaching his own conclusions. Lilty, articulate. A light Polish waltz across the vowels.

This was at Brigham Young University.

Every student in his charge had to audition for a spot in the class. They’d gather each morning at a “field house” for warm-up exercises: stretches and chants. Tad or “Mister D” conducting from the front. Watching. His slacks pleated and shoes clean. A button-down shirt with its cuffs down to his wrist. Neat and fastidious. One student recalls Tad rolling back his sleeves if he was warm, and on occasion even wearing something like a guayabera during the summer, but there’s another student who remembers (way more forcefully) that Tad never wore short sleeves, never peeled back the cuffs of his dress shirt because he hated to show his tattoo from the concentration camp.

He was buttoned-up. Private to the point of secrecy. One of his former students, who remained a friend and collaborator for 15 years, left several messages on Tad’s voicemail in the early 1990s, got no response, called back later and learned that he was dead. Quite suddenly, it seemed, of an illness he’d had for years. Another student with whom Tad was close says she learned of his death, as did several former students, only when they heard of the funeral.

There’s a vague woundedness here. Loved ones wondering if maybe they didn’t mean as much to him as they thought they did, if they were so out of the loop.

Another perspective says this is simply how he would have preferred it.

One former student tells me about his time on the production of Tad Danielewski’s Hamlet, the stage version, which was too innovative for television, too fourth-wall-breaking, and that part of what made his Hamlet unique was arguing that the prince isn’t scared to kill his uncle, King Claudius, it’s just that Claudius is surrounded, at all times, by a phalanx of guards. Tad dressed them up a bit like stormtroopers, helping some football players get their humanities credit. At one point, to give the audience a real sense of what the totalitarian state was like, Tad chose some quieter moment in the play (perhaps the scene of that play within the play), when the audience was likely to zone out, and that’s when he had his clanking, trotting, armored storm troopers “bang these doors” beside the audience,

swing em open, these guys coming in, and of course there’d be a plant [in the audience], you wouldn’t know who it was, and . . . they’d grab [the plant] out of the audience . . . and drag [him] out, he’s kicking and screaming, ‘You got the wrong guy!’ and the whole thing was to put fear in the audience about the power a dictator has.

That’s the same student who linked up with Tad years later in late 1980s Los Angeles after graduating from BYU. He was working on a reality show about standup comedians, kind of an early version of Last Comic Standing, and Tad said, “I’VE GOT THIS STUDENT, HE’S A COMEDIAN, HE’S SPECTACULAR,” but Eric said, “I’m sorry,” and then, telling the story on the phone 30 years later and probably not realizing the nuance, “I can’t open that door for you. They’ve already shot the thing.” This put a strain on their relationship but it didn’t reach a breaking point until a few months later when Tad was trying to get a sitcom off the ground:

The idea is you’d have a college setting and you have a person like Tad Danielewski . . . it would be like an acting school thing, and the students would be working on some classical bit, like Shakespeare or Greek theater, and outside of the classroom, or the workshop, life would be paralleling what was happening [in the play], and the two would merge in such a way that people [at home] could learn what was happening in Shakespeare, and see it resolved in what was happening in [these modern characters’] lives.

Tad tapped him to work on one of the scripts for this sitcom and Eric gave it a shot but ultimately decided “it was beyond me.” He submitted the outline he’d pulled together (which Tad liked) and then apologized. Backed out.

“Tad never took my calls after that.”

And this is how it would be. For everyone.

You were in or you were out.

Or else you felt left out, ignored, only for him to say something out of the blue to make you realize he’d been paying attention all along, noticing your strengths and weaknesses.

Some remember it as a defense mechanism, others as a kind of social tool for extracting favors. Several students tell me about a time in the 1980s when Tad got his former student, Martin Sheen, to visit his classes at BYU and talk about the business side of Hollywood. Then in the early 1990s, when Tad was out in California, one former student tells me about her boyfriend working as Sheen’s assistant, and how they were walking through LAX one day when Sheen, heading toward his terminal, allegedly spotted Tad from a distance and ducked for cover. “Let’s wait,” he told his assistant, anxious, “if that man sees me he’ll make me do something.”

Whether it was instinctive, a defense mechanism, or a social instrument, that disarming give-and-take of love and approval recurred in almost every one of my interviews with his former students.

And then, suddenly, my research took a turn, and I found some books that might reveal where it all came from.

Pearl & Tad

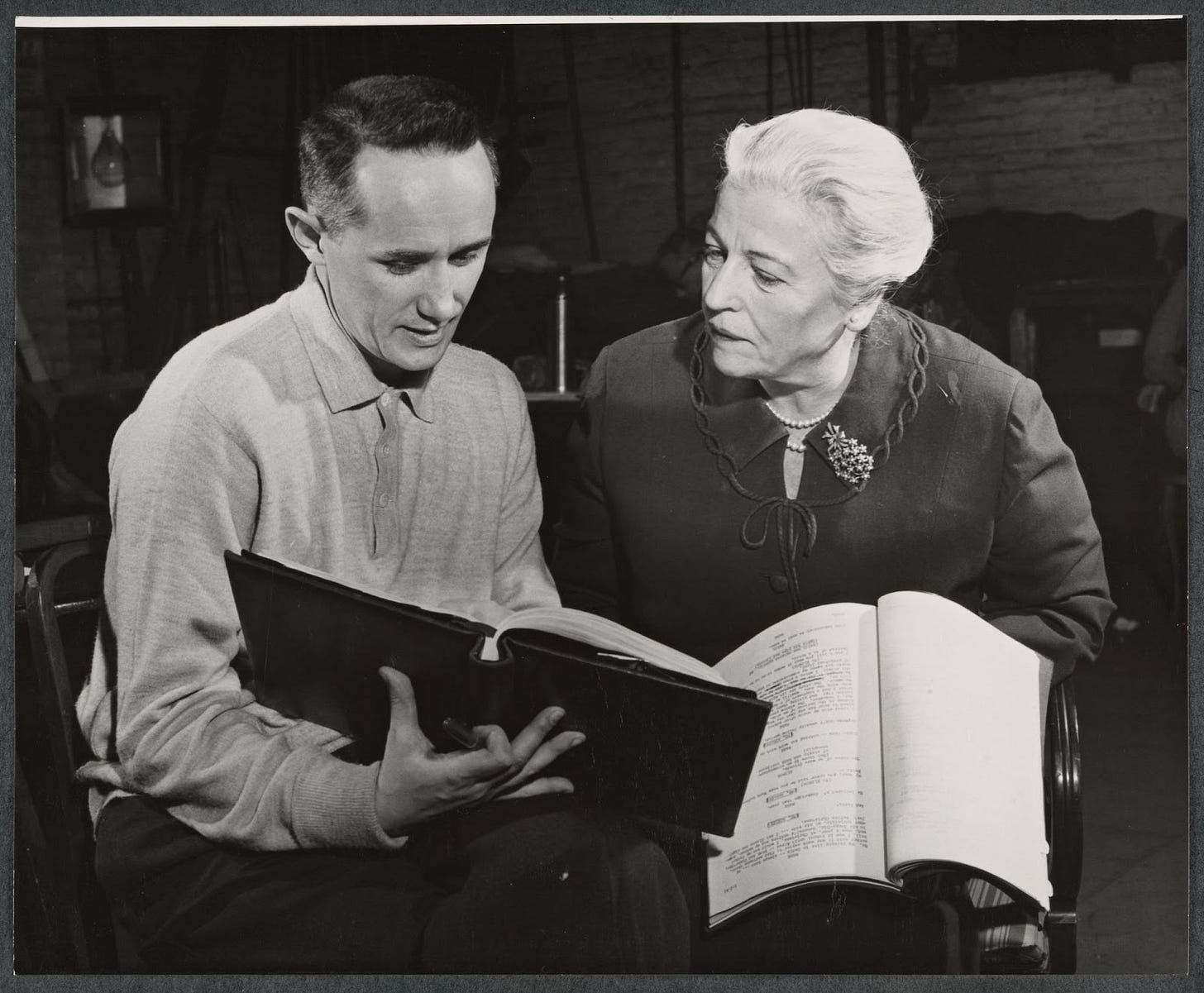

Online accounts of Tad Danielewski’s career are peppered with famous names of former students: Martin Sheen, James Earl Jones, Sigourney Weaver. But the celebrity who arguably played the largest role in shaping Tad’s career, the strongest hand in opening doors, seems to have been Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker Buck, better known by her pen name Pearl S. Buck. The first American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (1938), she was a worldly, wealthy, brilliant person whose early life was shaped by travel, church, and a shitty husband to whom she lost 18 years of her life before finally walking out, at age 43, finalizing one marriage and commencing another one that same day, trading rings with her editor, Richard Walsh, a mensch by all accounts with whom she spent the next couple decades in bliss, making books and children and piles of money, until Walsh, in 1953, suffered a stroke that left him basically bedridden until his death seven years later — a long and challenging window during which Buck, the breadwinner, was more and more frequently away from home, traveling.

She hired tutors to help her children while she was away, and nurses for her husband; she felt guilty for being away but also, maybe, a little guilty at how much she enjoyed herself. The acclaim, the company, the freedom (it’s touchy to mention) from the demands of caretaking.

This was when she met Tad.

I know how this next sentence will sound but stick with me. Pearl Buck was born in a West Virginia log cabin in 1892. Sounds far-removed from Borders and The Familiar and “What is iPod?” but I promise it’s not.

Buck’s parents were Christian missionaries by whom she was raised (along with six siblings) mostly in China, whose culture she loved and longed for the rest of her life. As friends and colleagues would later agree, the Pearl-Tad connection is rooted in the Nobel laureate’s own longheld sense of being — like the Polish, cerebral, Nazi-hunting filmmaker — a bit of an outsider.

She liked loners. Intellectuals. High-cultured expats were divine. If they were bookish and goodlooking, hey, so much the better, because Pearl Buck might look matronly, refined, whatever else; her hair chandeliered into the sort of gray-streaked bunnery you’d expect of a Nobel Woman of Letters, circa 1950; but she was frisky too. People had a hard time with that. How to take her jokes, her lingering glances, the more-than-friendly touches. As her friend Ruth Stills would later put it, talking about the senior Buck in that period, “I suppose that active sex may have been something she wasn't interested in any more, that she was too old. But the courtship part, the adoration, the flattery, the kiss on the back of the neck without actually having to go through with it . . . .”

Jackie Breen, who served as Buck’s secretary one summer during the Tad years, said that her employer, “Mrs. Walsh,” was quite sexual in her own way. Suggestive. Buck’s biographer, Nora Stirling, tells a story of Breen coming into work one day and telling Buck that she’d gone, the previous night, to see a movie called The Three Faces of Eve, whereupon Buck turned with a flirt and said, “Only three?”

“She had said once that no one man could satisfy her, and I'm sure that she needed more than one . . . . And as for that one young man, I think she was really in love with him. When he was around she preened herself. She glowed.”

Enter Tad.

In 1954, Buck visits the CBS studio where her novel, My Several Worlds, is being adapted into a TV movie by this slim, quiet, cerebral-seeming Polish guy who’s not been in the country very long. He’s cultured, though. Mysterious. Studied drama in London. Eloquent, with an accent. Plus look at that face. The intensity of it.

This intensity is what people seem to remember most about Tad. Even 30 years after his death, talking on the phone or through Zoom, everybody mentions how focused he was, perched on a director’s chair, or cupping his elbow and touching his chin and pacing the stage, the set, the auditorium, watching everything, remembering it; or else with his head low, thinking, rubbing his cheek, seeing nothing because, in his mind at least, he was someplace else.

It’s hard to say much about Tad’s pre-American life because it was defined by the war. Documents are scarce. He fought with the Polish underground and spent time in a concentration camp but nobody’s sure which one. He came to the United States with a pregnant wife, the actor Sylvia Daneel, and a quickly-ascendant career in television; he wasn’t keen to talk about what he’d endured at the hands of Nazis. He revealed things piecemeal, offhandedly, out of nowhere.

Brock d’Avignon is a former student who now, at 71, is basically Tad Danielewski’s historian, founder of taddanielewski.com, creator of a whole remembrance project where he encourages people to submit their memories of Tad for a kind of digital memorial.

Consistent across testimonies is that Tad was captured in 1943 and placed in a labor camp that was liberated by General George Patton — but he didn’t wear markers of the experience, nor did he talk about it. Once people knew it was there, however, they seemed to notice it constantly; “the armor,” as one former student called it:

The only time I saw [vulnerability] from him, in all the years I knew him, is when he was giving a talk about his life at a weekly devotional . . . . [H]e talked about his life experience, and he was [normal] “Tad” through the whole thing until he got to the part where his camp was liberated by Patton, and I finally saw the man behind the curtain. It only lasted a few minutes, and then he went back to “Tad.” But that’s what cemented [my impression] that he had constructed the part of himself that he presented to others, around this really horrific experience.

40 years after the war he's commanding the sets at BYU gently, talking softly, remembering everything about everyone except for their names, which means there was a lot of POINTING going on; lots of You, Him — Over There.

Nora Stirling quotes an interviewer in the Herald Tribune who writes of Tad that he is “Polish, blondish, slight, almost thin, very sure of himself and razor-sharp. No nonsense in conversation, speaks his mind softly and patiently but presumably could bite your head off. It is noticeable that the assembled actors in his class listen spell-bound to his comments.”

Everyone I speak with, if they knew Tad in the 1980s, remembers the toll of his second divorce. “It was traumatic,” said his friend and former student Lance Williams. “He went into a depression for quite a while. He just sorta receded from the entire college community.”

Brock d’Avignon would see his professor in the library at 8 or 9 p.m. during the week. Staying away from home. One night he went over to where Tad was sitting and spread out a map that he’d found in the stacks.

“I couldn’t read Polish,” he says, “but I could tell what it was.”

Tad looked at it. Then did a kind of double take. Then leaned over it. Loomed. A new focus coming to his face as he studied the landscape and then, “THERE,” smacking a finger down on some gray thread in a splotch of green. “THERE,” another thread, “THERE.”

“These,” Brock explains, “were all the places he blew up Nazi locomotives.”

He had this way of closing his arguments with both arms swelling over his head, like a conductor presiding over everything he’d just explained, one arm going higher than the other, into a fist, but the fist was always sideways, as if clutching something he was scared to lose, or hanging onto one of those hooks in a subway car, inflamed by his own ideas, so intense, the way he stood and stared and spoke and thought, even raged, visibly, but quietly.

“He was in constant inner turmoil,” said Williams, who auditioned for Tad’s BYU program in 1980. “I don’t think that the volatility was in his nature. In fact quite the contrary. I think that he was a quiet, peaceful human being. But because of the horrific experiences that he had in the war, it changed him . . . . I never saw him get out of control, [but] there were tense moments. Times when . . . you'd see the conflict raging, inside him.”

On her last day visiting CBS, Buck saw a producer walk onto the set of My Several Worlds and scold the young director, telling him the film was all wrong, not “commercial” enough. Tad was humiliated. Afterward, when the set was cleared, Buck went looking for him.

“He was standing [silently] with his face to the wall . . . I could see he was furiously angry but it was no use saying anything.”

Buck seems, by Nora Stirling’s account in A Woman in Conflict (1983) to have been enchanted by Tad almost immediately. Soon after they met at CBS, Buck suggested they collaborate on a play she’d been wanting to write about the atomic bomb; Tad’s first son, Christopher, had just been born, but he agreed and they traveled together, visiting Los Alamos, conducting interviews and taking notes and discussing the morality of the bomb, each of them passionate, full of ideas — a feverish pair that Stirling describes by way of physical contrast: Pearl Buck, “an overweight 63,” standing beside this “slim, active young man” who was “carefully attentive to the comfort and safety of his celebrated charge,” the one who shuttled him all over the West Coast into government research sites, hotels, and nice restaurants, settling every bill along the way.

Buck’s friends and colleagues wondered if “something” was going on between them, but nobody seems to have asked.

Their atom bomb play was called A Desert Incident. Tad, said one of Buck’s friends, “came to the house very often with his poodle” and brainstormed.

When the script was done, Pearl showed it to Oscar Hammerstein II (a songwriter for Oklahoma!, The King and I, and The Sound of Music). She said she was looking for feedback and Hammerstein tried to warn her of what she had on her hands with A Desert Incident, but she wouldn’t hear it, countering his critique by saying, of Tad, “I know star quality when I see it.”

A Desert Incident opened in New York City on March 24, 1959. The audience was cordial. The cast was quiet. They went for dinner at Buck’s place afterward and picked at their food, a radio crooning softly in the corner, everybody waiting for the first reviews to come through.

The New York Post wrote it up that week under the headline, “Further Evidence of Atomic Horror.”

The players were crushed.

Pearl was incensed.

Tad was contained.

The two of them rebounded by launching a film studio called Stratton, through which Tad would find the financing for his films and the two of them would travel the world.

It was sometime around here that Pearl Buck asked her sister Grace, “Do you think a person of my age could really fall in love again?”

Tad “appeared to be tireless,” partnering with Buck on several projects at once alongside his own stage productions. At one point they worked on a murder mystery, the idea being that Buck would write a novel, they’d collaborate on the script, and Tad would direct the feature.

Only Buck’s part came to fruition.

Another venture: Buck’s novel The Big Wave had been adapted into a one-hour TV drama that critics praised as a masterpiece, but Tad believed it would work better as a two-hour feature, shot on location in Japan.

Buck went along with it, distracted by her husband’s declining health.

She flew out to Japan to supervise the start of production, her mind still back home, claiming — by Stirling’s account — that she was here to make sure there was no international incident.

Meanwhile there’s Tad, the director, frustrated at having a Japanese counterpart on the set: “THERE CAN ONLY BE ONE DIRECTOR,” he told Buck, “IT IS I — OR IT IS NOT I.”

Buck said fine and the guy was removed.

As one of Buck’s friends would later say, of Tad, “I think he thought he was a brilliant young man.” But Stirling grapples with their dynamic, reiterating rumors that Buck “had given him a great deal of money,” and suggesting that, within the relationship, Buck played an authoritative hand (specifically, the one that feeds); meanwhile Tad’s production assistant, Jeanette Kamins, said that when she watched their collaboration in real time — Tad working his magic on stage with Buck watching, a script in her lap, constantly taking things out and putting them back — it seemed, to her, that Buck felt lost as a playwright. Flustered. Vulnerable.

“It was her money and her power that kept Danielewski in work,” Stirling concludes. “But he possessed power too.”

Their working relationship was often like an hourglass, turning over and over as one exhausted their influence over the other.

Stirling spoke to a witness from one of Tad’s stage shows (produced separately from his work with Buck over at Stratton) who saw that his wife would come to work each night, play her leading role — and then leave the theater quickly, alone, through the front door; later, through a side exit, went her husband, the director, on the arm of a young actress by the name of Priscilla Decatur.

At the wedding of Tad and Priscilla, Pearl Buck was an attentive, cordial, generous guest, later writing, “It was lovely, a garden wedding with a tent and orchestra and Priscilla in her grandmother’s wedding dress.”

More poignantly, then: “It was like a movie.”

Throughout the night, other guests at the wedding party noticed these forlorn looks the young groom was throwing at Buck, like it was Priscilla the Bride on his arm but Pearl the Lover on his mind.

Buck noticed them too, but kept her poise.

Later that night, driving away, she asked her sister Grace if she’d seen those glances.

Grace said yes, she had.

“What do you think they meant?”

Grace, relieved to think that the simmering drama of that relationship might finally be over, told her sister simply, “You know what they meant.”

With a sigh, Buck looked again out the window.

For a wedding gift, she doubled Tad’s salary at Stratton, and sent the newlyweds on a “business and honeymoon trip around the world.”

Pearl Buck got along just fine after that, her same industrious self, latching quickly onto the new, constant, reverent company of another young man, Theodore F. Harris, the future co-author of her “biography,” a work so much “In Consultation With” its subject that, in lieu of research, Harris simply quotes her for pages at a time, a post-game interview in which Buck — otherwise expansive and eloquent and wise — edits her yearslong collaboration with Tad to a couple of pages.

Meanwhile, around the time of Tad’s marriage to Priscilla, Buck confided in her diary one night that she’d spent her evening at the fireplace, burning letters to an unnamed lover.

A decade later she would confess to a friend that she’d expected Tad to marry her.

It’s worth emphasizing, of Buck, that she endured a miserable marriage and then — middle-aged, and at a time when the stigma for such things was great — walked out. Started over. Built her own life and career. Commanded the world’s highest literary honor. Served as the composed and dutiful caretaker for her husband, when he was ill, and then, when work beckoned, braved the guilt of pursuing it by hiring tutors for her kids, and nurses for the partner she knew she was abandoning to die alone. (As one doctor told her, while she stressed over the idea of abandoning him on her trip to Japan, “Go. He won’t know if you are here or not.”) At his funeral in 1960, her sister Grace recounts that mourners “gathered around the casket” and “[a]t that moment [Pearl] gave one indication of almost breaking down, just the way she caught her breath. But that was all.”

Widowed, Buck writes a memoir confronting her grief, and then, at Tad and Priscilla’s wedding, doesn’t just watch, with poise, as the man she loves moves on without her; she severs the attachment patiently, gracefully, not with a blade but a gift. Doubling his salary.

Buck stayed with Stratton for another couple years, gradually distancing herself. She gave him, and his new family, a head start.

She didn’t just open the door for Tad; she held it: “I believe in Tad Danielewski’s talent and it has been one of the interests which[,] at a time when I needed it[,] gave me a certain—what shall I say?—a diversion, perhaps. Certainly it enlarged my general knowledge of the world of the theater and television and films and had its effect on me. That is enough, don’t you think?”

Take Three

Larry McCaffery, with his wife and interview partner Sinda Gregory, read House of Leaves shortly after its release and reached out to Danielewski, requesting an interview.

Danielewski said sure.

And so they met up, Larry and Sinda and Mark, and talked for three hours. Everything went well.

But when Mark got the transcript, he didn’t like it.

He wasn’t upset, though! It’s a point of pride for Larry that no author has ever walked out of one of his interviews upset. Even if they were fussy or reluctant at first. He does his homework beforehand, reads all of the author’s work. His questions are intricate and they situate the subject within some larger tradition or discourse — he doesn’t flatter, doesn’t pander, but every line of his questioning is grouted with research, with respect, and authors (whom he explains are people who build their careers on wording things correctly and who thereby tend to live in some fear of explaining themselves the wrong way) ultimately relent.

They relax.

Actually one writer did back out, William Gaddis — which in hindsight doesn’t seem so bizarre; he was only agreeing to the interview because his publisher, Knopf, was leaning on him about These two guys, they’re doing a book of interviews, we’d like them to focus on in-house authors . . .

It wasn’t a big ask, and they’d been loyal through a career of less-than-commercial books, so when they asked him to help out, sit for the interview, Gaddis said sure. Grudgingly. And then it wasn’t Larry but his co-author, Tom LeClair, who schlepped out to Gaddis’ Upper East Side apartment in 1980, where the door was opened (as Tom would recount the episode) to reveal “a small man dressed — it’s been more than twenty-five years — quite elegantly, certainly in a jacket, possibly with an ascot.”

Gaddis ushered Tom inside, shut the door, and then pointed to a box of correspondence beside it.

“A lot of those are letters,” said Gaddis, “from people who wanted to interview me.”

And didn’t get the chance was the point he felt compelled to drive home. Gaddis would only give three or four interviews in his life. One of them on television, surprisingly, in 1986. It’s odd to see him there. So comfortable. Kinda handsome, too. He looks like Dick Cavett if Dick Cavett was miserable.

Nonetheless, his conversation with Tom was cordial and easy. “[W]hen we started talking,” Tom would later write, “Gaddis seemed to be quite pleased to be speaking about his work . . . [and] unexpectedly became garrulous, switching from thought to thought as his novels do.”

But afterward, when Tom followed up by sending over the transcript, it “went into that box by the door.”

“He was very litigious.” Tom sounding kinda demure here. “As you may know.”

When Gaddis tried ghosting, Tom threatened to publish the transcript as is, whereupon Gaddis threatened to sue.

The interview was dropped from Anything Can Happen, but Tom would publish the transcript almost 30 years later (“I just waited until he died”). But there were other headaches too, like showing up at Toni Morrison’s house and being told by her assistant to make an appointment, whereupon he told the assistant that he had an appointment already, at which point she doubled down, No you don’t, whereupon Tom went digging through all his shit to find the letter from Ms. Morrison herself proving that I do indeed have an appointment. Plus his tape recorder broke in front of Stanley Elkin. He gave up on interviews after Anything Can Happen.

Don DeLillo was a tough interview too. Like Gaddis, he hadn’t given many interviews and wasn’t keen to start, but Tom felt he was vital to this new literary movement and so they coerced and cajoled and finally the novelist relented and said fine, sure, he’ll do the interview — in Greece.

“He only agreed,” Tom says, “because he didn’t think I could get the money together to show up at Athens.”

When they met up, DeLillo handed him a card that said his name and, as a credential, “I Don’t Want to Talk About It.”

But the interview comes out great. One standout monologue, DeLillo riffing insightfully at Tom’s observation that “games are an important element” in his novels.

“People whose lives are not clearly shaped or marked off may feel a deep need for rules of some kind . . . . Most games are carefully structured. They satisfy a sense of order and they even have an element of dignity about them . . . . Games provide a frame in which we can try to be perfect. Within sixty-minute limits or one-hundred-yard limits or the limits of a game board, we can look for perfect moments or perfect structures.”

Tom was happy with the final product and sent the transcript out to DeLillo. DeLillo, he says, cut the transcript in half.

“We’ve been friends,” he clarifies, “but we’ve had problems since then.”

With what?

“With me trespassing on his privacy.”

Apparently DeLillo saw it as no coincidence that Tom took an apartment in Athens whose balcony “just happened” to look down on his balcony, where he’d go out in the afternoons and lie tanning for a while.

“I wrote something about his ‘skinny legs.’”

Tom LeClair’s review of The Familiar Volume 2, if you look beyond the implicit respect of such a close reading, is pretty damning, and he tells me without fuss that he quit the series after that, says he just didn’t see it going anywhere — but then, with zero hesitation, he slips into praising Danielewski’s first novel, which he’s taught many times, then gets into talking about the author himself.

“I will say that Mark Danielewski was one of the nicest, least-egocentric people to entertain.” He tells a story of hosting Danielewski for a visit to University of Cincinnati, where Tom was teaching House of Leaves to undergraduate and graduate students alike. Danielewski was set to speak with just the undergrads, but opted (against Tom’s suggestion) to speak with the grad students as well. They were “asking questions, offering interpretations, and Danielewski got rather frustrated and he said, ‘You will not tell me an interpretation that I haven’t already thought of.’ The grad students hated him. They thought he was extremely egocentric — but he was very open! He was answering the questions. Just nobody was going to spring something on him.”

I reached out to ask Tom about his experience on Anything Can Happen, and his impressions of those first two Familiar volumes that he reviewed in print. Based on his own experiences interviewing private authors of difficult work, and collaborating with Larry in some of those interviews, I asked what he made of Mark’s one-time riff, between Larry and Sinda, about his father, about “Redwood.”

“When they did that,” Tom says of the interviewers, “I was very impressed,” but he says he can’t imagine why the confession came out. He tells a story about Danielewski visiting his classes. Tom was teaching Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The Minister’s Black Veil,”

a story about a pastor hiding behind a veil, and [I told him] the students were doing well with it. Seeing things about it. Danielewski said, before the class began, he hadn’t read the story but, “I’d still like to see what you’ll do.” Halfway into class he raises his hand and gives his interpretation of “Black Veil.” I said, “Mark, you haven’t read the story.” He said, “I don’t think that’s a problem, given what’s been said about it.” He’s willing to interpret anything. Others’ reading of his work, he can be sensitive [about].

Larry McCaffery is something between Jerry Garcia and Fox Mulder. On the phone, even while driving, he has the voice of a man with elevated feet. He is proud to say that every work of scholarship he’s ever published has a reference to Bruce Springsteen. At no point in our several hours of conversation do I feel he is unprepared to talk about aliens. He and his wife Sinda share a home in Borrego Springs and they’ve been not just passionate readers but good friends with Danielewski for over 20 years now, ever since they sat for that first interview, what Mark remembers affectionately as “Take One,” and the follow-up.

Take Two, Larry says, had different questions, but a bit of overlap. “The stuff about his father,” said Larry, “I don’t think he’s ever explained it the same way that he did in our interview.”

Same goes for his remarks about “Redwood.”

In the interview, Danielewski says he was working low-wage jobs when he got word that Tad was dying. He rode a Greyhound bus to LA for three days and wrote the whole time. A longish story called “Redwood.”

Tad, he said, was enraged at the story, in part because it was “so much about him.”

In a later interview, Danielewski will describe that 1992 version of “Redwood” as being “a story about a tiger that isn’t really a tiger.”

A character named Redwood appears in House of Leaves, but only for one line. It’s in a diary entry from Zampano, the blind film expert and quasi-father figure for the book’s young hero.

Zampano writes: “Redwood. I saw him once a long time ago when I was young. I ran away and luckily, or no luck at all, he did not follow me. But now I cannot run and anyway this time I am certain he would follow.”