My friend, I’ve decided this will be the last piece I ever send you. You’ve been my editor for, what, forty years now? Forty-five? Jesus, you know I love you, dear man — dearest — and always will. But this is it. Consider it my resignation, if that much matters. You and I both know I’m well past retirement. And though I know we always said we’d never let ’em lick us, that we’d never let it get us down, yet I’m tired, old man. Tired, and I want to leave this city. While I still have time. A little time. The things I’ve seen . . .

You — you were meant for this place. Or it for you. I knew that from the moment we met. But me? No sir, never was. Only ever made it this long on grit. Spite and spittle, as the old grandam used to say. But they’ve done me in, now — the kids. Yessir, it’s the end for me. It’s the nether limit. As far as I’m concerned, this beat won’t be around much longer anyways — so yes, it’s my last review. Do with it what you will. I don’t really care. I’m tired. I’m leaving.

The Death of the Artist is what he called his exhibit. This so-called artist. So doubting that any of these kids ever read their Barthes anymore, I took myself all the way down to Lower Manhattan and resolved to see it. It was down in the Gallery Nouveau, you remember that old place? Kittering used to own it. Made the Voice go bananas over all the lovely gunk he put up on the walls, and the clutter. I remember all those hagridden cabbies, always left circling and circling until their Upper East Side customers were done and finally ready to lunge back home, before the junkies and the women of the night crawled out their holes and filled up the sidewalk again. Ah, what lovely days it was, Gene. Lovely days. Can’t you remember?

Well but now the spot’s as clean as can be. Sure, there’s still Joe’s B-Side across the street, and thank god. But besides that, the Nouveau these days is as bright and shiny as a battleship in peacetime. Nothing but egg-white walls and fluorescent lights, beaming evilly out through the sheerest of plexiglass windows. Sandwiched between a Pilates place and a Sweetgreen — and the clientele’s the same all around, you can bet. I showed up a half hour late, thinking I’d be early. But the kids these days, they actually run things on time! (Is there any surer sign, Gene, that the culture has stagnated than a youth that cares about punctuality?). Yes, gone is the New York of sleeping in late. Gone is showing up to parties as they were finishing, or keeping the bars and dens open long after hours. Gone, too, is Doris, Queen of 32nd Street. Remember her, Gene? How she used to take us boys in the back and [redacted]? And then big Audie Rysler would say, “Jiminy Cricket, but that really takes the cake!” and we’d all fall down laughing and ramble home drunk. Yes, lovely days it was, Gene. Lovely days it was.

Alright. Alright. Nostalgia’s a poison. I know. Anyways, some kid had told me. Told me about the Death of the Artist. Positively raving about this hot young conceptual freak, some fresh coastal specimen who’d rented the place for one night only, on the last of his grant money, and set up his installations. Installations which this kid kept insisting to me were going to be the definitive treatment, the real thing, to sum up the century so far, and all the hip children’s malaise. And sure, I was an old-timer, from some near-dead old-world publication (no offence, Gene), but still, even the rearguard ought to be present at the crowning of the vanguard, right? Some nonsense like that. What can I say? He appealed to my vanity. We hate youth, but still we find nothing more seductive than a chance to play hip-with-it again, even just for one more titrated moment. Even just for an evening.

So I waddled on down to the Lower East Side — late, as I said — only to find a few dissociated clumps of twenty- and thirty-somethings milling around, sipping champagne (champagne!) and murmuring about “middle-period” this and “multimedia” that. I took out my pad and my pen and I started to mill around, too, hoping at least one of these “installations” would merit a scribble. Of course, none of them did: I couldn’t bring myself to make a note, so pat it all was, so dull, predictable. Found objects, readymades, wickerwork, a box fan pointed at a wall, some wall texts about indigeneity (though why or how, I couldn’t quite figure, as I’d been told the artist was, like us, your classical white gay, bien pensant). I would’ve almost taken it for a satire on the new art world itself, Gene, if it hadn’t all been so prosaic, so utterly, contemptibly contemporary. Still, perhaps there was fun to be had. A laugh — or whatever comes closest to it, in this denuded landscape we once called a city.

1. Vesuvium Effluvium

What do I remember — let’s see. First up a big floorspace showing, looking like nothing less than a twelve-year-old’s science-class diorama. The diorama’s base maybe eight feet by eight feet — not shabby — with a volcano in its center, perhaps four feet tall, perhaps five. Every few minutes a little light would click on and the mouth of the volcano would bubble over in frothy white, milk-looking, semen-looking fluid, which would pour down like lava over the sides. Then the little scale models of homes and cars and people and cats and dogs, scattered around the volcano’s base, would be swamped by the white, starchy flood — whole villages and populations drowning in semen, gurgling in it. Then the light would flick off, the liquid would pool and collect and be funneled back by some pipe mechanism into the caldera of the volcano. Then, in a few minutes, it would bubble over again. I looked at the text on the floor — Vesuvium Effluvium, it was called. And yes, that gave me a good chuckle. Not great by any means. Tacky. Obvious. But worth a nice, approvingly homosexual chuckle. What artist wouldn’t drown the world in his own spunk, if he could?

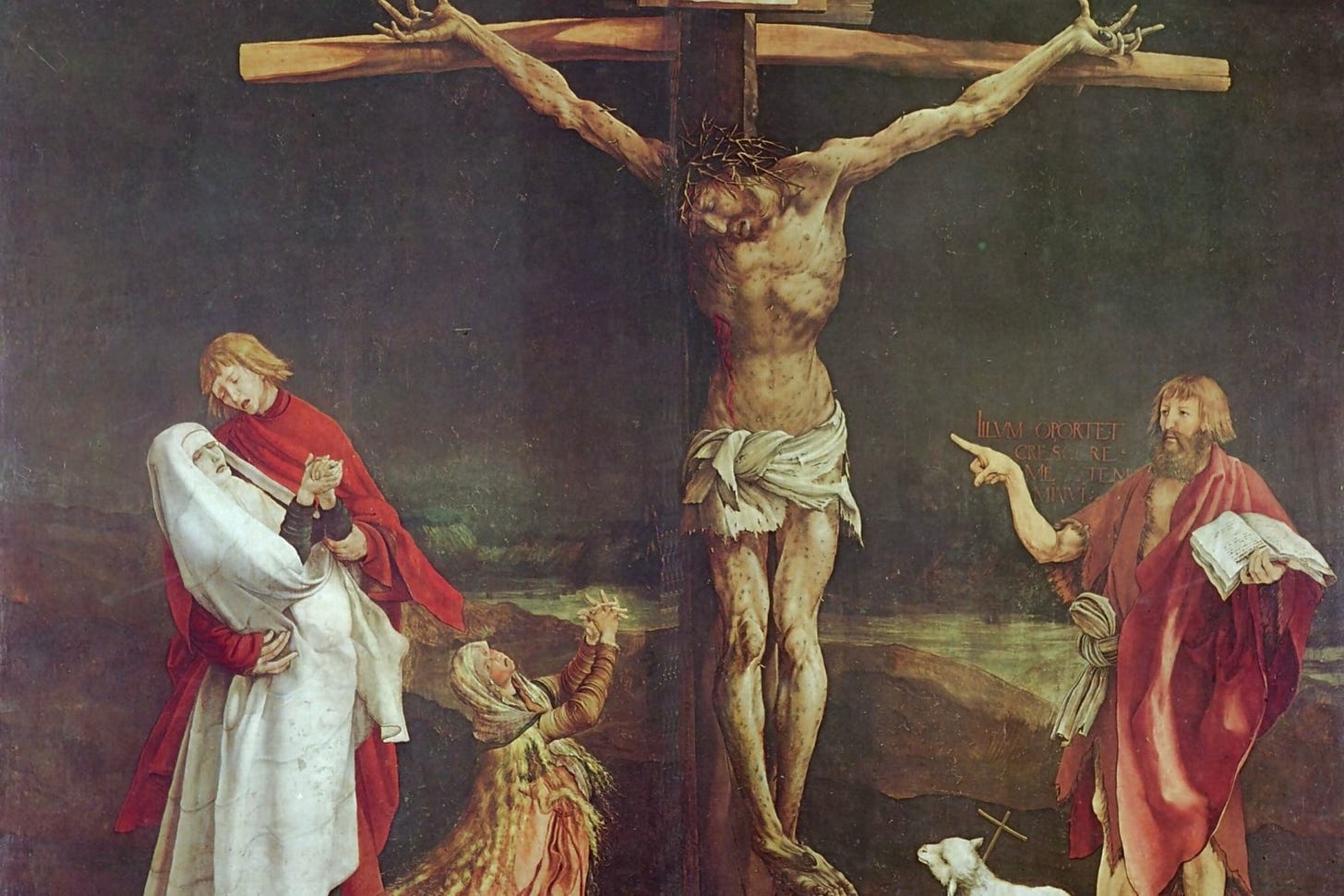

2. The Stations of the Cross

Well, so then next came fourteen little square-frame paintings. One for each Station of the Cross, naturally, which of course these kids would never have understood if there hadn’t been a text announcing them as such. But each painting was, to my eye, nothing more than a neat little mockery of some Italianate Renaissance classic or other, only with an obvious half-nude figure of the artist himself painted into the scene where Christ ought to be. Here was the artist, shouldering his big olive-wood cross, as a crew of gleeful Romans whipped and scourged him from behind. Here was a treacly Pietà, of the artist on his knees in the road, with Mother Mary leaning down to cradle him — his lips scandalously close to the Dame’s holy teat. Each of the artist’s falls on that road to Golgotha, in that roaring crowd, rendered with such sweet subjective self-pity and hubris — all derivative. Beyond derivative.

Such is the apotheosis of the artist’s wet dream, I suppose: to be the martyred Christ. And Jesus, but these kids are as obvious as can be. How does anybody stand these shows, Gene? Tell me. How does anyone stand around and sip that champagne and murmur about technique when confronted with such dull — such on-the-nose — spectacle? It was beyond me, it really was. Here was this Ivy League boy, educated, surely handsome, and well-off. A gay boy in the third decade of the twenty-first century, which is the best we’ve ever had it. And he’s making — what — a volcanic tribute to his organ? A paneled disquisition on his own savior-sized dimensions? Get me out, I thought. Death of the Artist — I only hope it’s literal, I thought.

But there was more, as the steady inflation of the great artistic ego reached a stupendous climax halfway through this absurd Christly tetradecatych. There, in the middle of the progression, I came upon a little podium. And on this podium — I kid you not, Gene — on this podium was an interactive crown of thorns. Yes. You could pick it up, look at it, put it on. Be me, the text below it said. Be me, for a moment. Well you know what, I thought, realizing right then that this was going to be my last show ever as a critic, because I would never again stand for trawling through one of these egg-white galleries, in one of these gentrified hoods, in a town I never really loved anyways — I thought, fuck it, sure, I’ll be him for moment. See what it’s like to think you’re Jesus Christ Himself. So I took the damn thing and turned it around in my hands a few times, and pricked a finger or two (though it wasn’t that sharp), and I set it on my head.

Well then, I thought, I am he. I’m the death of the artist. I am D.O.A. Then I ambled over to the next few paintings but I was surprised — surprised, Gene! — to discover I liked the next one. This one was different. Panel 8 or 9, I believe. It was a painting of Jesus (the artist, that is) meeting the woman of Jerusalem. But I was amazed — astonished, even — to discover that instead of another self-transposition into vague Renaissance relief, this painting appeared to be nearly melting. Melting in a huge, vivid series of red rivulets, cascading down from the top of the painting like deep red tears, slowly blotting out the painting. A lovely effect, I thought. A fine little conceptual idea which, to my mind, almost (almost) turned the series from disaster into a somewhat affecting — or at least effective — work. But what was stranger, the red seemed to keep increasing as I looked at it. Growing, running further and further down the face of the painting, until . . .

3. The Bathroom

Well, Gene, I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that the red was my own blood getting in my eyes, leaking down from where the thorns had cut into my forehead. A couple kids nearby laughed at that, at my ridiculous appearance, my mistake. (“What’re you laughing at?” I wanted to say, “This is the only thing making the art tolerable!”) But I acquiesced and took it off, put it back where I’d got it, and rushed off to the bathroom.

It was a nice bathroom. I remember the shitholes (literally, shit holes) we used to tolerate, Gene, even in the nicer galleries back in the day. And of course, smelly and tetanus-ridden as they were, you’d still have to muscle your way past some pair of customers copulating in the corner just to piss.

Not so in the new world, Gene. Not so. This restroom was all marbly white tiles, stalls graffitiless, mirror wide and as sparkling clean as a battleship in peacetime. I looked for a moment at my old gray visage, my homosexual nose, the pockmarks, the little red forehead scratches leaking blood down my face. I took some tissue paper, tried to sop up what I could, cleaned and pressed the cuts for a few minutes. Even used a bit of the gin I had in my flask to disinfect it (I refuse to drink champagne — Gene, you know this). In five minutes I felt fine, only a little light stinging from the cuts. And there was a voice in my head which said: Stay here a while. It’s nice in this bathroom. Even this pockmarked, nasally gay face you’ve found in the mirror is nicer than whatever the primping youth of New York City could summon for a showing, in a time and place as miserable as this.

But I knew I had to make it out eventually, and it might as well be soon. I’d go to Joe’s B-Side, I thought. Have a drink for old times, write this piece, send it off to you, Gene. Then, having made my final peace with my final piece, I’d quit this dying city for good and go see what kind of retirement is most dignified for an old art critic in exile. For now, though, I’d see it through. I’d step out and discover just what happens to Jesus in the end, whatever trite conclusions the artist had conjured to summarize the obvious demise of the entire downtown scene. And then I’d be free, and I’d never have to worry about another well-off, happily gay young artist again.

4. Some More Bad Paintings

It shouldn’t surprise you that, cleared of the red haze, the paintings had gone back to being unremarkable, self-indulgent pabulum. Finally I made it to the end, in which our Christly artist was, shockingly, hanged on the cross, then expired, then was taken down, then laid in his tomb. Not a moment of artistic thought in the whole of it. Not even in the tomb — with the great and holy Shroud of Turin laid across his pale, lovely, artist-like limbs — did this contemporary Jesus do anything but look like the bloodless and beatific god-child of some old Italian iconographer. What was I supposed to make of it? Barnett Newman did his Stations in zips in ’66 and that was moving. I was there! I saw it. But they could tolerate abstraction in those days, Gene. They had teeth and brains, and none of that obviousness, none of the self-concern on display here, I thought. By this point I didn’t bother to read the wall texts. I’d seen what I needed to see.

5. The Death of the Artist

There was only one thing left: the titular installation. But Gene, this was the crudest, most pretentious of them all! It almost resembled a real person. In a waxen, artificial way — it was almost surreally real, I suppose. But still totally, laughably crude and unrealistic, this fake corpse that hung from the gallery rafters. The effigy of the artist: a nice, thick hemp rope tied to a beam in the ceiling, and the waxy-looking life-sized figure dangling from it, swaying a bit to one side in the draft whenever someone opened the gallery door. I looked at it just long enough to get what I needed from it. I laughed at the little placard: La Mort de l’auteur, it read, in the French. And under it: Ceci n’est pas un artiste. This is not an artist. God, I chuckled at that, Gene. Derivative — beyond derivative. All that miserable build-up (imagine the hubris necessary to actually paint yourself into the Crucifixion, without a thought to making it good), and for what? A joke about a suicide, and Barthes, and Magritte. And not even a lifelike mock-up of a body at that. But a total, obvious, ridiculous-looking fake.

There were a few young women with vaguely disconcerted looks in their eyes, starting to prod with their fingers at the effigy’s shoes, so I decided to leave for good. Had they never encountered contemporary art before? Jesus, I mean, all it’s ever about is tacky conceptual drivel like that. Or else it’s blood and genitals and dead bodies and fluids, and young hip people play-acting like little heretical pagans, but upsetting who, exactly? The blue-chips? The auctioneers? The rich men and rich women still happily shelling out hundreds of thousands — millions! — of dollars for anal beads or blank canvases or wicker chairs? Jesus. This used to be a real city, Gene. God, I used to love this city.

But I’ll admit even I thought it strange the artist himself wasn’t present. At his own opening. You’d think a young man like that, so full of his own martyrdom, so obviously marveling at his own virility — you’d think such an upstart crow would be practically preening, practically peacocking (!) at the gates of his own opening-night exhibition. But no: nowhere to be seen. Maybe he thought he was being mysterious, who knows. I think more likely afraid — afraid to meet an old head like me, probably, and have to measure up his own indulgent crap against all the timeless masterpieces I’ve seen. Me, who once watched Mark Rothko paint, who once fucked (and was fucked by) Jasper Johns. Who once watched the incomparable Doris, Queen of 32nd Street, take big Audie Rysler in her masculine hands and [redacted].

Anyways, I finally got out into the road and stumbled over to Joe’s, reveling in the glow of those low green lights again. I marveled at the jukebox still spitting out Platters tunes in the corner, and I saw Joe Jr. behind the bar, as usual, and I ordered a beer and a shot of whiskey. Then I was transported, for a moment, back to that time — to those days, Gene, when it all meant something. When the world was ugly but the world was good. Across the street, at the gallery, a crowd had formed. Maybe the artist had finally shown up, I don’t know. Some people were applauding. Some of the young women appeared to be screaming. There were sirens in the distance. I wasn’t about to look back, wasn’t about to waste any more time thinking about the nonsense of youth and youthful scenes.

No, I was too busy enjoying my beer and my whiskey, dreaming of retired life upstate or in Santa Fe. Humming along as the Platters sang “The Great Pretender” and “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” and a dozen other numbers that seemed to stretch and distend my very soul through time, back to the days when it was just us — you and me, Gene — with the whole world to conquer. Before this shitty scene went to bedlam, before the money and the metropolitan crews, and all these young artists who think they’re the next Jesus Christ came pouring into our city to ruin it. Like the hot white magma of volcanic phalluses — phalluses of artists who can’t even show up to their own opening nights. But then what can I say? These New York artists, Gene — they’ve always been cowards.

Sam Jennings, The Metropolitan Review’s film critic, is an American writer living in London. He is the Poetry Editor at The Hinternet, and he runs his own Substack, Vita Contemplativa. For those interested, his Letterboxd account can be found here.

I really love this piece, thank you for the laughs!

Now I realize me harassing George Plimpton half-naked and vomiting at CBGB'S in 2003 was the last time New York saw a real Puke Christ.

The letter is framed as a resignation, a closing of the books after decades of labor, but what it reveals — perhaps in spite of itself — is less an ending than another iteration of performance. In his supposed departure, the critic can't resist staging one final exhibition of his own: himself, the weary figure who dons the crown of thorns, bleeds onto the gallery floor, and transfigures his wound into commentary.