Ruyan Meng’s second novel, The Morgue Keeper, follows the exhausted, ultraresilient Qing Yuan, a morgue attendant in Mao’s China who runs afoul of the vengeful state while investigating the mysterious death of an unidentified woman known only as “number 19.” The book is harrowing in the strict etymological sense, not in the cloudy uprooted sense with which the word is often deployed: it left me feeling like I’d been scraped over by a plough’s tines. Cut into, yes, and a bit sore, yes, but also more open, more fertile of mind. Last thing I read that left me so earnestly non-metaphorically nauseous (and happy for it) was Andrei Platonov’s Foundation Pit (in Robert Chandler, Elizabeth Chandler, and Olga Meerson’s fabulous 2009 translation for New York Review Books).

But my stomach is not the two novels’ only overlap.

The Stalinist brutality whose foundations Platonov digs out is, in Meng’s own conception, not just the precursor but the mentor of the regime that mobs her morgue keeper. Meng wrote, in an essay on Maoist “worker villages” for Red Hen Press’ Medium site, that

the Soviet Union was considered the “beacon of Communism” and the “big brother” of the Chinese. The regime would often send high officials on trips to Moscow to learn from the Soviets. The Communist party termed such a trip “qujing” (取经 “in search of enlightenment”—a phrase from the Ming Dynasty novel Journey to the West).

But Platonov’s novel was itself an exile, like so many other classics of Soviet dystopian fiction (Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, Andrei Sinyavsky’s Pkhentz, and so on and on), in the sense that it was first published abroad and in translation as tamizdat (literally “published over there”). Meng’s Morgue Keeper, however, is a work of exile.

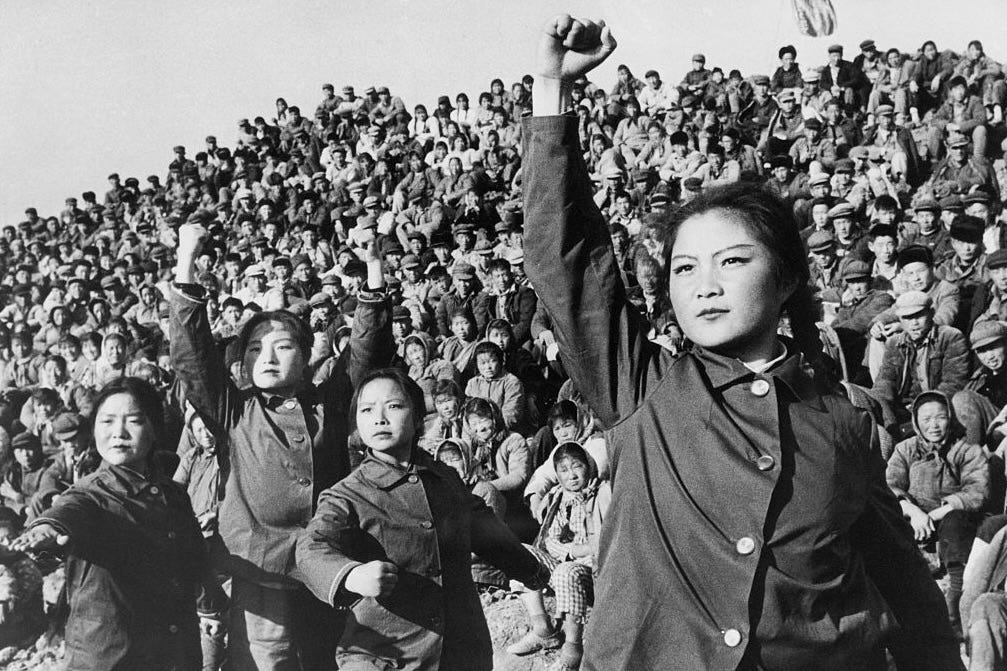

Having lived, like her novel’s protagonist, in a Maoist worker village through the ’60s and ’70s, Ruyan Meng fled to the U.S. after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in ’89. She set up shop(s) as a business founder then real estate investor in Dallas — Mao is not just turning, but doing wacky somersaults in his grave. She published her first novel, Only the Cat Knows (Red Hen Press, 2022), in non-translated English.

And the exilic nature of her English — the studious obsessiveness, the aggressive curiosity required of one who would write in a language acquired and mastered in adulthood — grants The Morgue Keeper a linguistic idiosyncrasy and richness of wordplay that allows it to transcend the polemical vitriol to which it sometimes threatens to succumb. From the novel’s first paragraph:

Thirty-seven, Qing Yuan thought when a cleaner wheeled the corpse of a woman into the morgue. The woman’s husband, a scrawny man in a shabby work uniform, smelling of sewage, drooped behind the gurney. The cleaner pushed a form to Qing Yuan and fled. He glanced at it: Dystocia with stillborn boy.

For the most part, just vibrant and descriptive prose. We know the deceased was married, that her husband is poor, how he looks, how he smells, how he lives, to some extent, after only three sentences. But the studiousness and obsessiveness and curiosity of exile reveal themselves in a glorious pun, a piece of wordplay that crosses the jargon of medicine with the tiramisu levels of communist euphemism: the woman died of “dystocia,” of “obstructed labor.”

That hardworking villainy of a pun is not the groan-inducing, cheap-illusion type — though Lord knows I adore those, too. A good pun, whether of the groan-mongering or of Meng’s careful-machined type, cuts through the lexile-textile veil of Maya to give us a glimpse of the tenuous chaos of ambivalences and approximations that supposedly clear, solid language tries to hide. Meng sees this, and so her wordplay is picked with pointed precision: she cuts through both English, with its tangled etymological knots, and the Mandarin which her novel’s setting implies as substrate, both by denying each language the phony simplicity of one word = one meaning lexicality, and by tying the languages together.

(A tangent—not in the sense that I’m digressing, but in the geometrical sense, that I’ll focus on a line of thought that touches the novel’s circle at one point, at a location and angle that helps to define the circle itself — a tangent, that is, to highlight one particularly brilliant piece of wordplay which Meng scatters throughout her novel and which exemplifies perfectly the kind of weaponized wordplay I’m talking about.

After the Norman Invasion of England in the 11th Century, Britain was ruled by native French-speakers for about four centuries. Richard’s uncrowning by Henry IV in Shakespeare’s Richard II memorializes the turn, hence Lord Mowbray’s tearful pleas against exile in Act I: “The language I have spoke these forty years, my native English, now I must forego, and now my tongue’s use is to me no more than an unstringed viol or a harp.” He’s not just sad. He’s explaining to Richard what Anglophone monolingualism is like, since Richard, as heir to the Norman conquerors, has never experienced it.

That is, for 400 years, as English moved from Old through Middle to Early Modern, the higher classes in England spoke in haughty Latinate French-ish, and the lower classes spoke something closer, at first, to modern Frisian, a stolidly Germanic tongue. The servant/served linguistic gap of that period persists still today, not only in what we consider “dirty” language (Germanic “fuck” or “shit” or “piss”; French “copulate,” “defecate,” “urinate”), but especially in culinary language. The animal in the field is Germanic: a cow. A pig. A deer. On the table, it’s Latinate: beef. Pork. Venison.

Each time Qing Yuan buys food, whether at the hospital cafeteria or at the take-out joint by his worker village, Meng describes the receptacle into which he takes it as a “pail.” It’s jarring at first: “pail” is a subtly old-fashioned word in any case, almost totally supplanted now by “bucket,” and I’ve not once in my life heard someone talk of putting food for a person in a pail—maybe slop for pigs, chicken feed, water for plants. The word connotes labor. But there is not an easy, obviously French, culinary equivalent for it. Maybe “pitcher”? But there is no clean synonym. For what Qing Yuan is using to store his cabbage soup, most folks revert to the clunkily adjectival “to-go container” or somesuch compound.

But — and this, I think, is Meng’s brilliance — “pail” comes most likely from Latin via Old French, and from the same Latin word that we’ve appropriated, all these years later, to talk about knee-caps: patella.

So Meng has, in that simple but persistent use of “pail,” foreignized our relationship to her prose, even though it’s not a translation, by finding and hammering on a contradiction to the usual French-eating/German-laboring distinction that shapes English agricultural and culinary speech. The fact that the origin of “pail” isn’t rendered self-evident by looking at the word is icing on the well layered cake she’s cooked us.

I am not, she implies, writing about a country in which such linguistic class distinctions as those imposed by the Norman Invasion apply. But I am, she implies, writing in a way that uses those distinctions as only a particularly obsessive wordophile from outside those distinctions can: not only is her usage of “pail” in pointed contradiction to the usual Germanic-Latinate agricultural-culinary distinction, but it implies by etymology that those whose food is served thus are forced to kneel on their patellas for it. It is an etymological critique both of English’s construction and of Mao’s Republic.)

That sort of . . . not a linguistic flourish — it’s much too invisible-to-sonar for that — but that sort of subtle, layered barb, is not an exceptional case in Meng’s prose, but a thoroughgoing rule. At the very beginning, after that gorgeous pun on “dystocia,” the deceased woman’s husband signs the papers to hand her corpse over to the morgue, but he signs with “what looked to Qing Yuan like a chicken’s clawprint in the sand.” Another multileveled, far-reaching piece of wordplay: the poor man’s signature was like an inverted peace sign, as used so optimistically by western leftists around the same time that Qing Yuan and his friends and neighbors are being railroaded by Mao.

Son of an “enemy of the state,” Qing Yuan has not chosen to work in the morgue. When his father, a jeweler, was arrested and murdered for having (allegedly) hid precious metals from the Cultural Revolution’s expropriators, Qing Yuan was conscripted to morgue duty. Fellow persona non grata Lao Jia trains and mentors him, and by the time we meet the two, they’re best friends. Qing Yuan has no idea why Lao Jia was forced into the morgue and even less idea why his mentor must live in the hospital bunks rather than receiving a room in Worker Village: Lao Jia “had been a Kuomintang POW. He’d labored for two years in a camp. He had worked in a brothel. That his dossier said as much didn’t prove these things. The dossier itself was the truth.”

Which is to say, whatever appears in state-sanctioned print is truth, so the novel abandons truth as a serious (or, say, as an interrogatable) subject. Later, when Lao Jia disappears at the same time posters declaring him an enemy of the people appear all over the hospital, the posters supplant his dossier as truth. But by then, Meng has no reason to tell us why or to comment on the phenomenon. When Qing Yuan is similarly denounced, Meng offers just as little rationale.

I’m left to assume things. His father was a damned capitalist, so Qing Yuan has committed something like original sin; he didn’t take part in Lao Jia’s struggle session, so he’s clearly harboring anticommunist sympathies; he’s asked around about number 19’s mysterious death, and somebody in the Party wants to keep that quiet. . . . Meng allows me to assume all, some, or none of the above, and by trusting her reader so deeply, by abandoning any claim to authorial monopoly on truth, she escapes the charge of anticommunist propaganda—Vladimir Nabokov’s ghost, though suspicious, does not finally accuse her of “poshlust,” of writing in the political-moralistic rather than the aesthetic mode.

That is, in The Morgue Keeper, we’re far from the propagandistic world of something like Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, equally far from the bluntly antipropaganda propaganda of Orwell’s 1984, though comparisons to those novels would be super reasonable and likely fruitful. As a propagandist, Meng’s strength is that she refrains from propagandizing: by refusing to endow the destructions of Lao Jia’s and Qing Yuan’s lives with reasons, she pointedly casts the political conditions of the early People’s Republic not as against reason, but as totally separate from it. In Qing Yuan’s world, truth is a matter of policy, not observation, much less justification.

He does not need to be accused of a concrete crime before he’s denounced. The notion that he might be so accused is, in the world Meng builds, absurd, or at best redundant. His only crime is that someone with more party cred than he — he, who has labored faithfully in the position the party assigned him for almost two decades and has not protested even slightly — has decided that he is not totally mobilized in favor of the party, so he can’t be trusted, so he must be treated as though he has done the sort of thing an active enemy would have done.

But Qing Yuan’s story does not end with his first denunciation or its immediate aftermath: unlike many of his fellow accused, he survives with his mind intact — seemingly because he recognizes from the outset the absurdity of his situation. While his fellows delusionally claim that “the Party could never harm a good person” and that “confusions and misunderstandings are entirely understandable” but will surely be corrected, Qing Yuan compares himself to the biblical Job and to the characters of “poor little Kafka.”

That is, Qing Yuan is not only the novel’s narrative center, but its central conduit to metanarrative (and thus to the linguistic trickery we talked about earlier).

After he is released from prison, Meng’s language shifts to include not only pointed foreignizations of familiar historical divides in English (like that tangential “pail”), but also jarring spatial dislocations: Qing Yuan, hobbling and weak and filthy after his denunciation, finds some money and buys cigarettes, not at a dialect-neutral “corner store” or “tobacconist,” but at a “bodega.”

Likewise, the novel’s play on Meng’s native Chinese grows thicker. From his aunt, Qing Yuan receives a contraband kitten named Xi’er. Having lost all else but his job in the morgue (there is a romantic subplot about which I’d rather not write; it’s too touching, and I’d rather not rob readers of encountering it first in Meng’s text by summarizing it in mine), taking care of Xi’er keeps Qing Yuan going, gives him an intense sense of purpose. When she disappears from his bag in the morgue lockers, he runs out into the street, and “in the dark of the blazing day, he called out for Xi’er. Meow, he cooed, meow, meow.”

In Mandarin, the word for “cat” is an onomatopoeia: “mao.” Pronounced with a hint of diphthong after the “m,” a bit like English “meow.” Having been brutalized by Mao’s regime, Qing Yuan calls out for his beloved “mao” by shouting “mao” — although, in Meng’s phrase, he does not shout; he “coo[s].” Same pronunciation, though past-tense, as “coup,” as in “coup d’etat.”

Devotion to his own mao, voiced as “meow, meow,” is his resistance against Mao, is Qing Yuan’s personal coo/coup, after many long years of faithful, soul-sucking service in the morgue. When the state does not just represent its citizens, but claims the democratic apotheosis of being embodied in each citizen, so that each citizen in fact represents the state in minuscule — that is, when the state claims and impels total mobilization of each body’s and mind’s every faculty — even a small denial is revolution at personal scale: not just treason, but proof positive against the founding theology of the state itself. This is a triumphant climax, in its oblique, sad way, both at narratological and semantic scales.

Here, too, as in Meng’s first novel’s title, Only the Cat Knows. Only the cat, the phonetic counterpart to the ruler, the chairman in punning minuscule as each comrade is the People’s Republic in minuscule, can know and “no.”

I know I haven’t said all that much about the quality of The Morgue Keeper in general — no touting it as a “tour de force” or “ambitious and timely,” no panning it as just “ambitious” or “polemical.” To do so would be redundant and, in fact, demeaning; from its first page, Meng’s novel is forceful and difficult, both for the mind and for the body. Some will love it. I did. Some will be forced out of it at about the halfway point, if not later, near the romance subplot’s denouement.

This novel deserves, however, a far closer and more fine-grained read (and re-read) than the workaday praise/pan review allows. Meng’s linguistic fire, the obsessive care of her exilic wordplay, is less like the sparks-and-smoke fireworks of a Conrad or a Nabokov than like the fire that smolders underground along a coal vein, hollowing a town’s foundations for years or decades before finally, before anyone’s feet have burned on tarmac, or anyone’s olfactory sense has smelled the old deep factory’s smog, Main Street collapses. And The Morgue Keeper, like any good coal-vein fire, is well worth the dangers of an exploratory dig.

Jonah Howell is a writer and translator in New York. You can find his other criticism at Cracks in Postmodernity, The Cleveland Review of Books, and The Rumpus.

How do you not also recall that "lunchpail" used to be the term for what construction workers and other workers used to carry their lunches to work? Now we call them "lunchboxes" or other, branded terms. But "pail" makes perfect sense in this sense as well.

Excellent account of what seems like a very important work, thank you. One point: original sin is not 'committed': rather, in Christian doctrine, it's the default and unavoidable human condition; so the parallel with being born into a 'capitalist' family is entirely apt, because both are inherited, rather than personally incurred.