In the late 1980s, New York was a city on the brink.

Wall Street boomed, and white-collar New York rejoiced; blue-collar New York, after decades of disinvestment, became an inferno, as the Black and Hispanic working class was pitted against white ethnics. Racial strife, embodied by several successive and increasingly high-profile beatings and killings, seized the consciousness of a beleaguered municipality. Tens of thousands slept on the streets every night, many of them poor and mentally ill, while thousands more were ravaged by a mysterious illness. All the while, New York City proved slow and ill-equipped to stop their suffering. The once-beloved mayor, who had rescued New York from the edge of bankruptcy, saw his administration undone by corruption scandals and a lack of empathy for the plight of Black New Yorkers. Without a doubt, the zeitgeist was one of crisis.

This story, told by Jonathan Mahler in his new nonfiction chronicle The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990, follows four main characters: Ed Koch, struggling to keep the city together amid what would be his final term; Al Sharpton, the polarizing civil rights leader, equal parts charlatan and outspoken advocate for the marginalized; Rudy Giuliani, a ruthless prosecutor with dubious motivations about to launch a storied political career; and Donald Trump, then a tabloid fixture known for his shady real estate deals and imploding casinos. Interspersed is Brooklyn filmmaker Spike Lee, orbiting the release of Do the Right Thing, and AIDS activist Larry Kramer, who assailed the closeted mayor to do more to save his dying friends. They are thoughtfully portrayed, as is the lesser-known story of Benjamin Ward, the city’s first African American police commissioner, forced to navigate his role leading the NYPD as support for both the department and Koch cratered in Black neighborhoods. The changing culture of the city’s neighborhoods, from the Upper East Side to Bedford-Stuyvesant, is well detailed by Mahler’s prose.

Yet, the consistent — and most intriguing — throughline of Mahler’s story concerns the tumultuous period of race relations in the late ’80s and how those forces shaped the city’s politics in the three decades thereafter. The book begins two years removed from the “Subway Vigilante” shootings, in which recluse Bernard Goetz shot four Black teenagers, paralyzing one, who allegedly tried to rob him. Mahler covers the response to the trial — a Rorschach test of race, vigilante justice, and self-defense — where Goetz was acquitted of all serious charges, precipitating a groundswell of outrage in the Black community. This was only the beginning.

While Goetz was sitting in court, Michael Griffith and two friends, all Black, sought help for car trouble in the predominantly Italian, 95% white neighborhood of Howard Beach. At the local pizzeria, they were beaten by a group of white youths who shouted racial epithets and brandished tire irons. Griffith, attempting to escape, was chased onto the Belt Parkway, only to be fatally struck by a passing car. His assailants were eventually convicted, but only of manslaughter. Throughout, Mahler’s portrayals of the city’s worst racially motivated crimes — incidents that would define the era — are empathetic, detailed, and thoughtful.

In both instances, Al Sharpton, doughy and dressed in a tracksuit, emerged as a major leader. Unapologetically radical, Sharpton allied himself with Black militants, such as Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam, and openly resented most politicians, white or Black. After Howard Beach, Sharpton organized a large demonstration through the exclusively white waterfront enclave. Griffith’s family did not trust the police, but they trusted him, leverage that Sharpton used to cajole Governor Mario Cuomo into appointing a special prosecutor for the case. Always eyed warily by the media class, Sharpton soon proved their skepticism was warranted. In 1987, Sharpton eagerly brought publicity to the case of Tawana Brawley, a Black teenager from Wappingers Falls, missing for four days, only to be found in a garbage bag covered in feces and racial slurs. Brawley, 15, along with Sharpton and allies Alton Maddox and C. Vernon Mason, refused to cooperate with law enforcement and accused the local police of covering up the crime. State Attorney General Robert Abrams convened a grand jury, which concluded that no crime ever took place. Sharpton doubled down, comparing Abrams, a liberal Jew with a strong record on civil rights, to an oppressor on par with Adolf Hitler, while assailing a Black legislative ally as “Uncle Tom.”

When the case was exposed as a hoax, Sharpton became a pariah. Jesse Jackson refused to acknowledge him at the Democratic National Convention. Koch decried him as “Al Charlatan.” For years, Black leaders in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant attempted to recruit a challenger to dethrone Koch, to no avail. Sharpton made the task more difficult; Bill Lynch, the top strategist for David Dinkins, told him, “Don’t fuck with me, Al.”

After coasting to re-election twice, there was ample reason to believe Ed Koch was vulnerable. Queens Borough President Donald Manes, a longstanding ally of the mayor, plunged a knife into his chest rather than face prison. City for Sale, written by muckrakers Wayne Barrett and Jack Newfield, exposed a network of corruption throughout the administration, casting Rudy Giuliani, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, as the white knight exposing wrongdoing. Polling showed Giuliani, whose high-profile prosecutions of mobsters and white-collar executives earned him great press, handily defeating Koch. Nonetheless, the incumbent’s greatest worries came from within the Democratic coalition; any movement to dethrone Koch would have to be built around Black voters. The seeds were planted during the 1988 Democratic presidential primary.

Jesse Jackson, in his second bid for the White House, was surging against the milquetoast Michael Dukakis. A gifted preacher, talented organizer, and former aide to Dr. King, Jackson strove to build a “Rainbow Coalition” of union workers, Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, poor people, and youth. After a stunning upset over Dukakis in white working-class Michigan, Jackson, on the precipice of history, fell short in Wisconsin and Arizona. On April 19, New York would be his last stand. Koch, aggrieved by Jackson’s prior comments, in which he referred to the state as “Hymietown,” aggressively and personally attacked the Black insurgent. A consistently vocal ally of the pro-Palestine left, Jackson was routinely branded an anti-Semite by Koch and his allies.

While Jackson lost New York state, effectively ending his chances of capturing the nomination, he won a majority of the vote in the five boroughs. Not only had Jackson expanded and energized the Black electorate to an extent previously unseen through years of voter registration drives, he successfully courted large Puerto Rican constituencies in the Bronx and Brooklyn, marrying support from the city’s racial minorities with white progressives. Chants of “our time in ’89,” a nod to the upcoming mayoral election, serenaded the Jackson watch party.

If there is, perhaps, one missed opportunity in The Gods of New York, it would be with respect to the Rainbow Coalition. The arc of Black political power in New York City is well-chronicled by Mahler, but a complementary narrative on the changing composition of the city’s public sector unions — from Irish-dominated to a working-class lifeline for Black and Puerto Rican workers — would have been useful. Labor, once the hallmark of the urban Democratic coalition, played a pivotal role in the campaigns of both Jackson and Dinkins, but has declined in collective political and institutional influence since.

David Dinkins, the mild-mannered Manhattan borough president who co-chaired Jackson’s New York campaign, was poised to inherit Jackson’s coalition. A creature of the local machine, the soft-spoken Dinkins was not the rabble-rouser Sharpton was, nor did his pro-Israel politics polarize liberal Jews in the manner Jackson’s support for Yasser Arafat had. (A greater exploration of the era’s Israel-Palestine politics would have been welcome.) Yet as Dinkins spoke of healing the “gorgeous mosaic,” the eyes of the city and of the nation focused intensely on his backyard in Harlem. They did not see a mosaic or a melting pot, but a nightmare.

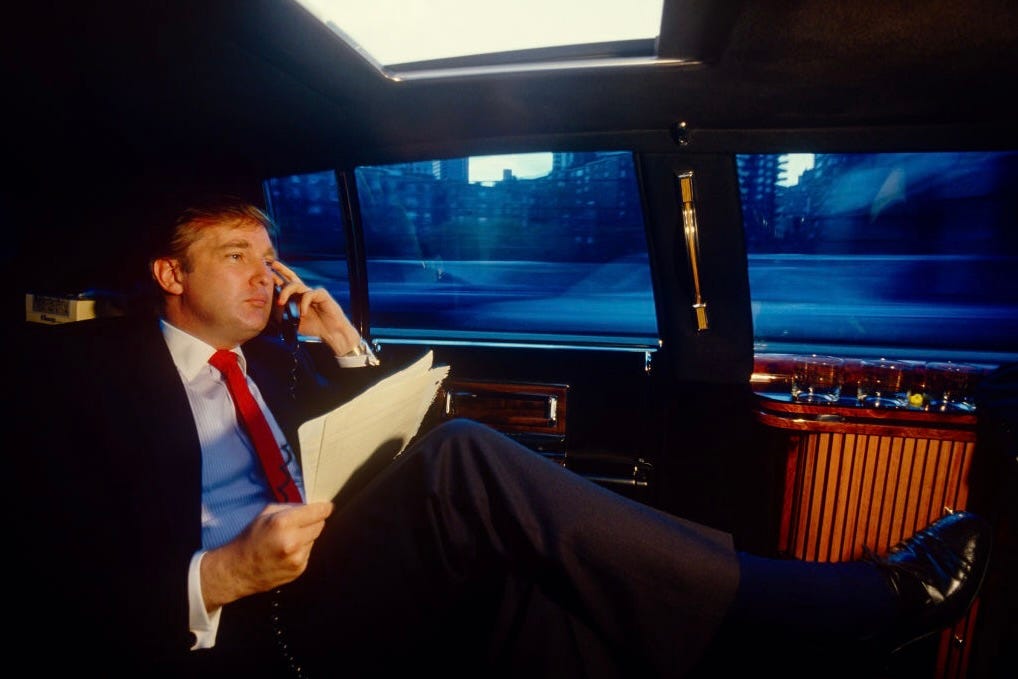

The Central Park jogger case — in which a young white woman was found beaten and unconscious, and five Black and Hispanic teenagers were coerced into false confessions — marked Donald Trump’s first, and most explicit, foray into politics. Until this juncture, Trump was a creature of the tabloids, mainly interested in seeing his name in print, expanding his real estate empire in Manhattan and Atlantic City, and having affairs, including the one with Marla Maples that would end his first marriage. Nonetheless, Trump took out full-page advertisements in each of the city’s daily newspapers, calling for the death penalty against the alleged attackers, who had not been convicted. Trump’s cruelty was widely criticized by the media, but his assumption of guilt was not. While the rush to judgement was not Trump’s alone — many public figures agreed with him — a handful of Harlem officials, including Bill Perkins, questioned the official story. The teenagers soon recanted their confessions, and, despite no physical evidence linking them to the crime, were convicted. As white fear spread, Koch, once left for dead in the polls, slowly climbed back.

In 1977, Koch, campaigning against “poverty pimps” and in favor of the death penalty, had ridden a similar wave of backlash to a come-from-behind upset. Dinkins’ predecessor, Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton, was long tapped as the most likely to be the city’s first Black mayor. However, the fallout from large-scale rioting, which engulfed entire neighborhoods as a result of a 25-hour blackout, ultimately doomed Sutton, who saw his support from white voters collapse, a saga well-detailed in Mahler’s first book, Ladies and Gentleman, the Bronx is Burning. The jogger case threatened to do the same to David Dinkins.

Then Yusef Hawkins was murdered.

Hawkins was in the wrong place at the wrong time and died for nothing other than walking while Black in a white neighborhood. Like Michael Griffith in Howard Beach, Hawkins was killed in an Italian American enclave, Bensonhurst, where there were scarcely any Black residents. When Koch’s police commissioner called him with the news, he urged the mayor not to visit the precinct right away so as not to risk inflaming racial tensions. Sharpton, indicted for tax fraud and in a state of political exile — the families of the accused in the Central Park jogger case had rebuffed his services — was contacted by Hawkins’ father, who lived in East New York. He hoped Sharpton could draw attention to his son’s death.

Sharpton obliged, leading a march through the heart of Bensonhurst. At the funeral, he sat alongside the Hawkins family in the front row. One of their guests, Jesse Jackson, made an insensitive but nonetheless prescient comment to Mr. Hawkins: “That boy laying in that casket could be the reason David Dinkins becomes mayor.” When Koch first ran for mayor 12 years prior, African Americans and Puerto Ricans were unorganized voting blocs, supplementary pieces of a citywide coalition. Now, they were strong enough to topple him. Indeed, in this moment of peril, Koch had proven incapable of uniting the city, which had only grown more divided during his tenure. An everyman who thrived walking the streets of the five boroughs, Koch, in contrast to his rival and predecessor John Lindsay, consistently struggled to relate to the city’s growing Black population. As Ronald Reagan realigned the Republican Party, many of Koch’s more conservative supporters left the Democratic Party, which had begun to orient itself towards affluent liberals and lower-income Blacks and Latinos.

On Primary Day, Koch brought out his voters: Hasidim and Orthodox Jews in Borough Park and Midwood, Greeks in Astoria, Italians in Staten Island and the East Bronx, Poles in Greenpoint, Russian Jews in Sheepshead Bay, Anglo-Saxon Protestants on the Upper East Side, middle-class Jews in Riverdale and Forest Hills, and the Irish of Maspeth and Woodlawn. Once, that had been the recipe for a mandate, a permanent governing coalition. Now it was not enough for a majority. The white working class was not only leaving New York City but the Democratic Party broadly.

They would never return.

Roughly 60% of Koch’s primary voters defected to Giuliani in the general election. After failing to fashion himself as a liberal reformer in the mold of La Guardia or Lindsay, Giuliani, with the assistance of GOP strategist Roger Ailes, pivoted hard to the right. New York City was once the epicenter of Rockefeller Republicanism, an upper-crust aristocracy of Park Avenue; now it would herald the forthcoming realignment of the white working class, injected into the zeitgeist by Donald Trump decades later. Bensonhurst, where Dinkins had been so careful to urge calm, went to Giuliani by a 10-to-1 margin. In Giuliani’s relentless attacks on Dinkins, for tax delinquency and crime, there are not only echoes of Trump’s open letter about the Central Park jogger, but also his campaign message when he descended the golden escalator. In 1989, the Rainbow Coalition was enough for Dinkins to prevail, despite Giuliani supporters claiming the outcome was “rigged.” Four years later, as the pressures detailed by Mahler further metastasized, it would not be. For the next 20 years, no Democrat would lead City Hall.

Since 1989, Black voters have become the bedrock of the Democratic coalition in New York City. However, under the weight of record-breaking crime in the early ’90s, complicated by the Crown Heights riot, Dinkins could not tame the ungovernable city, and the Rainbow Coalition buckled. In the following years, the movement that swept Dinkins into office began to fracture; labor unions defected to Republican incumbents, tensions between Black and Hispanic leaders rose, liberal Jews were alienated, and grassroots enthusiasm cratered. Many Democrats, including prominent Black leaders, tacitly supported Giuliani and Bloomberg. It took 20 years for Bill de Blasio, once a volunteer for Dinkins, to reclaim City Hall.

Sharpton, the anti-politician, ironically embodied this dynamic well. During his vanity runs for the Senate in 1992 and 1996, he received infinitesimal support outside of the Black community. In 1997, after placing second in the Democratic primary for mayor, he waited until the last minute to endorse Ruth Messinger against Giuliani. In 2001, in advance of the general election, Sharpton urged other Black leaders to sit out the race, helping the Republican nominee, Michael Bloomberg, win. David Dinkins not only inspired Black voters but also maintained buy-in from Latino leaders and progressive Jews in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Sharpton had little desire to strengthen the coalition of Dinkins and Jackson.

Eric Adams, the current New York City mayor, comes in many respects from the Sharpton school of politics. Both were allies of Louis Farrakhan, the leader of the Nation of Islam, until they were not, becoming staunch supporters of Israel. While Dinkins was fighting for re-election, Adams, one of the highest-ranking Black officers in the police department, was undermining him. Building cross-racial coalitions — Adams criticized the first Puerto Rican congressman, Herman Badillo, for having a Jewish wife — was of little interest to him. But where Sharpton gravitated toward outside agitation, Adams relished the inside baseball. When Adams ran for mayor, he did so as a tough talker from the outer boroughs who made liberals squeamish, becoming the resounding first choice of blue-collar New York, dwindling but still diverse. Similar to Koch, the former police officer leaned into crime and disorder — not to spark white backlash against racial minorities, but to inspire Blacks, Hispanics, and Hasidic Jews to reject the progressive orthodoxy of the college-educated elite. This was the last gasp of old New York, but few recognized it at the time.

As the Adams administration descended into chaos and corruption, the mayor was ultimately spared jail by an unlikely ally: President Donald Trump. After watching New York City’s “Middle Americans” leave the Democratic Party decades ago, Trump nationalized Giuliani’s 1993 backlash campaign perfectly in 2016, shattering the so-called blue wall in the white-working class Upper Midwest. Trump, though, remained a pariah in much of New York City, earning a paltry 16% of the vote. He changed his voter registration to his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, but the real estate developer from Jamaica Estates never lost interest in his hometown. Every four years, Trump expanded his foothold in New York City. Now it was not only the white working class, but the Hispanic working poor and the Asian middle class. The southern shore of Staten Island, a refuge for the Italian exodus, became the greatest Republican stronghold in the Northeast. Bensonhurst, now majority Chinese, gave Trump 60% in 2024. Corona, a low-income immigrant thoroughfare beneath the 7 train, which had broken for Obama and Clinton by margins of 9-to-1, delivered a slim majority to the man intent on mass deportations. The Rainbow Coalition was reduced to tatters.

But from the ashes arose hope. The crises of the late 1980s, as damaging and fraught as they were, also bred generational political opportunity and advancement. Dinkins’ victory, a seminal moment in the city’s history, would not have come without the corruption and strife that, momentarily, wove together a diverse coalition. In 2025, a similar concurrence of crises, macro and micro — the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuomo’s resignation as governor, the corruption of the Adams administration, unprecedented unaffordability, and Trump’s return to power — has led to the election of Zohran Mamdani. Dinkins could not tame the crises of the city, these macro political and economic forces that did not disappear when he entered office. He only served one term as a result. While the city is far healthier now than it was 30 years ago — there were 2,262 murders in 1990, compared with 286 in 2024 — the challenges awaiting a potential mayor Mamdani are significant. Trump, who frequently refers to Mamdani as a “communist,” has mused about sending the National Guard to the five boroughs and freezing federal funds traditionally earmarked for the city.

Mamdani himself, born in October 1991, came of age in the New York City that arrived after The Gods of New York. Nonetheless, the message of his breakthrough campaign, rooted in opposition to corruption and income inequality, can be traced to the late ’80s. Koch assailed Jackson for insufficiently supporting Israel, only to see the progressive presidential candidate win a majority in the five boroughs. Now Cuomo blasts Mamdani as too anti-Israel, and he’s already been throttled in a primary. The victory of Dinkins, a card-carrying member of the Democratic Socialists of America, foreshadowed, in some ways, the rise of Mamdani, a cadre democratic socialist. These were triumphs rooted in the power of people seeing themselves in a political movement for the first time. While the white ethnic middle class may have left the five boroughs in the 36 years since, Mamdani has reoriented the city’s politics around the new age middle class, the first Democrat to win without the affluent elite or the Black political establishment in decades. Most consequentially, Mamdani has become a model for how the Democratic Party can answer Donald Trump, championing an authentic politics rooted in the working and middle classes to build the broadest coalition possible.

To understand why, look to The Gods of New York.

Michael Lange is a writer and political analyst who covers New York City politics on his Substack, The Narrative Wars.

Great review. Looking forward to reading the book. Mr. Lange knows the city' political history very well. I suspect even better than that of Mr. Mahler.

The 1988 NY presidential primary where Jackson, the candidate of the left, edged out Dukakis in the city is an interesting precursor to this year’s mayoral election. But unlike Mamdani, the base of Jackson’s support was overwhelming support from Black voters.

Racial polarization in the city was much much greater than it is today. Michael Griffin, Yusuf Hawkins, Central Park 5, Bernard Goetz, Tawana Brawley, skyrocketing cime, etc. You could feel it on the street and on the subway.

According to a New York Times/CBS News exit poll of 2,100 voters, Jackson won 93 percent of black votes. He only won 15 percent of the ballots of whites.

And the rhetoric and atmosphere surrounding the Giulaini-Dinkins races ('89 and'93) was especially ugly

Thankfully, however intense are the city’s divisions today, they are not so starkly drawn along racial lines as they were back then.

Can't wait to read this. I grew up in NYC in the 80s and 90s and my political beliefs and feelings about the city are firmly shaped by the subjects of this book. Though I find the title weird.