PHOTOGRAPHY BY MAX VADUKUL

INK BY JASON CHATFIELD

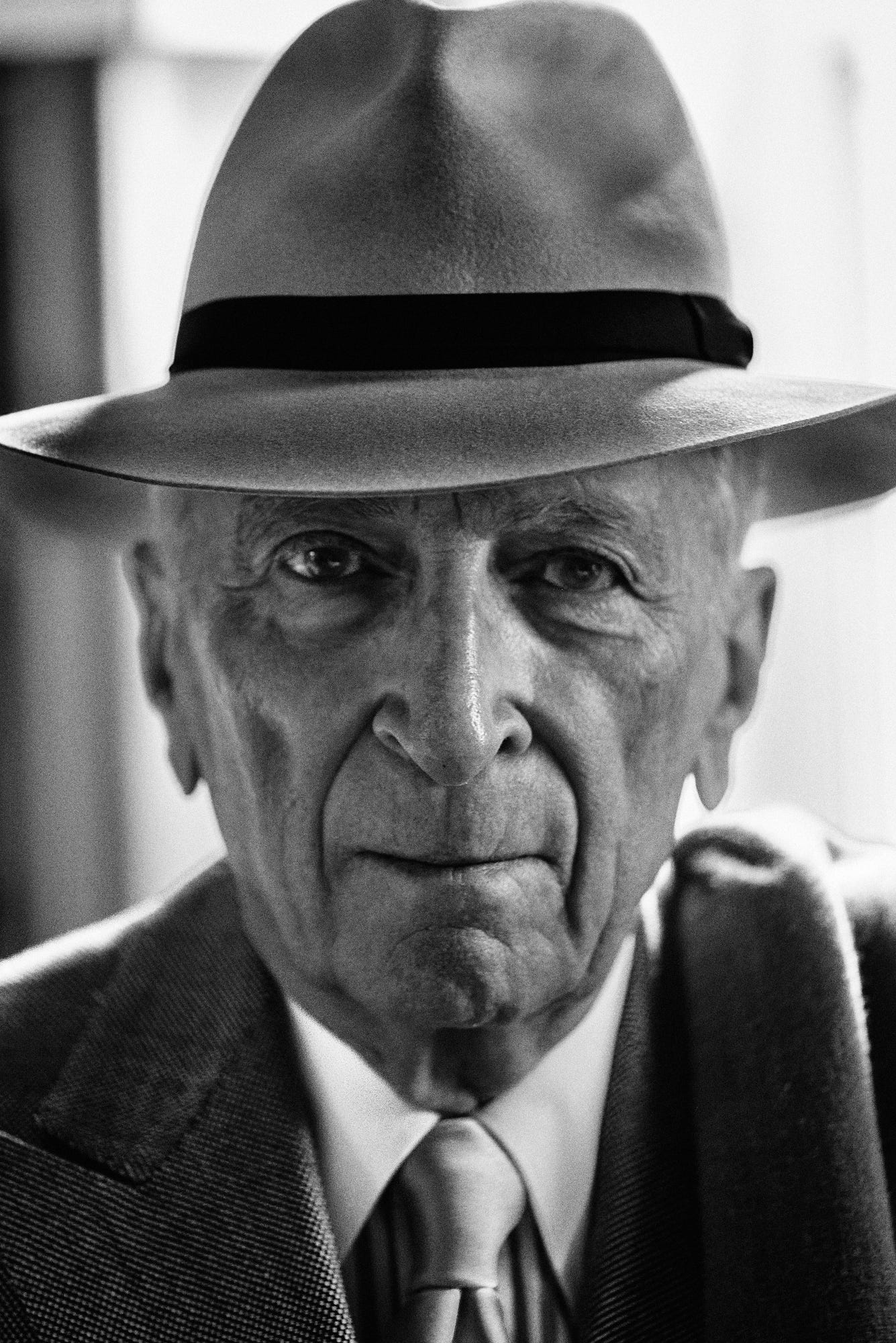

It is the rarest of gifts to have lived long enough to survey both a life and a century in its greatest breadth; even rarer still to be both an active participant and shaper of the currents, to have walked alongside the titans of the age and brought them, somehow, to fuller life. This is the shorthand for understanding Gay Talese, and it’s nearly correct: Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio, in two immortalized magazine profiles, will be bound to this boy from Ocean City, New Jersey, forevermore. But Talese will be the first to tell you that “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” is not his greatest work, nor the one he is most proud of. For a man who has dwelt, in one form or another, in a magnificent Manhattan townhouse since the 1950s — though it was not so splendid when he moved in as a mere twentysomething tenant, before it acquired its opulent grandeur over decades of his loving attention and escalating magazine fees — he has always been most at home with the men and women in the shadows, the ironworkers and sex workers and mobsters, not to mention the city’s scruffy alley cats.

Today, Talese is 93 and the very last of his kind: the dashing literary lion, the writer-celebrity, the pulsing center of a high culture that has, to our detriment, grown frailer. Among his contemporaries were Tom Wolfe, Nora Ephron, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Jimmy Breslin, and Pete Hamill; some he counted as close friends and others, as he’ll readily tell you, could irk him. To state that Talese is not an ordinary nonagenarian is like declaring that the New York Yankees, his favorite ballclub, are not a mere athletic franchise; we at The Metropolitan Review strain not to be so obvious. But sometimes, that’s where the truth lies.

On a warm afternoon in August, we had the pleasure of visiting Talese to conduct an interview that lasted nearly three hours and ranged over every topic conceivable: Sinatra, Trump, boxing, adultery, the writing life, the nudist life, the importance of dressing well. He will tell you, casually, about the time Styron occupied an upstairs bedroom to belt out what would become The Confessions of Nat Turner, or how Philip Roth’s first wife would come barging in at the strangest hours. He talks frankly about how deeply he loves his wife, Nan, a powerful book editor who is, at 91, still his wife despite a publicly turbulent marriage that was once on the brink of divorce.

His memory remains impeccable, and he will apologize profusely for forgetting whether a reporting trip of his occurred in ’98 or ’99. On the afternoon we met him, he wore a cream-colored three-piece suit that, he later pointed out, was one of the few not specifically tailored for him by a cousin in Italy. There are concessions to age that he openly resents: the elegant cane he uses from time to time and a sense of taste now mostly lost. He laments that he doesn’t get out nearly as much as he used to, though he still keeps “rock star hours,” up very late because of his nocturnal penchant for watching movies. He’s sure, at this point, he’s seen almost every film ever made. Writing is more of a chore because of a hand tremor, but up until 90, he says he had very few health problems.

Talese is strikingly undiminished, both regal and sprightly, not merely a bridge to the glittering midcentury but a full embodiment of its promise. Born into the maw of the Great Depression, he rose from newspaper copy boy to literary icon, reaping the rewards of a trade once flush with opportunity. What he remained above all was a reporter, bearing witness wherever he went, immersing himself for months or years at a time in a person’s life or culture. That, for him, was the prize of his trade: the hanging out, the cataloging, and, when possible, the elevating of the marginal and the vanquished. Decades ago, he would periodically wind up in the owner’s box at Yankee Stadium with a brash real estate developer named Donald Trump. Talese, who lives not far from Trump Tower, would sometimes find himself taking rides home with Trump, who was always willing to gab and court journalists. But Talese never wrote a profile of the future president. The already famous, the so-called winners, were not terribly interesting to him. He’d rather file dispatches on Floyd Patterson, felled twice by Sonny Liston, or those who never enjoyed the glory of a heavyweight title to begin with. This is apparent in his latest collection of reportage, A Town Without Time, which gathers up much of his New York work and excerpts from seminal writings on the Italian Mafia, the New York Times newsroom, and the ironworkers who built what was once the largest suspension bridge on earth. Wedged in too, of course, is a certain piece about a certain crooner who caught a cold.

Below is our conversation with Talese, condensed and edited lightly for clarity. We are deeply indebted to Max Vadukul for his never-before-published black-and-white portraits and to Jason Chatfield, The Metropolitan Review’s Cartoon Editor, for his wondrous Talesian illustrations. With warm special thanks to Alex Vadukul.

—The Editors

THE METROPOLITAN REVIEW

You are the last literary journalism lion of your generation.

GAY TALESE

Sometimes I look at a photograph I keep on the fourth floor of my townhouse that Annie Leibovitz took for Vanity Fair of me, Tom Wolfe, Nora Ephron, Bob Silvers, Breslin, Hamill, Trillin. Everybody’s gone except me and Bud Trillin. Who’s alive now of my generation?

TMR

Of those major writers, none. How does it feel to be the one that’s —

TALESE

That’s still alive?

TMR

How’s the writing life at 93?

TALESE

I’m trying to do it, but I have trouble typing. My hand shakes and I can’t write or sign things so well. When you’re 93, there are a dozen things wrong with you, and you can’t name them all.

TMR

You seem to have a healthy sense of your own mortality. How does it feel to hold so much time within you?

TALESE

Well, I’ve aged a lot between 90 and 93. At 92, I was going out more and I didn’t have a cane. I hadn’t lost my taste. That makes a big difference. But I’m still alive. I go out once in a while. Not often, because I don’t like to leave my wife, Nan, who doesn’t walk without help. She’s such a good-spirited person. If I couldn’t walk, I’d be such a grumpy person. She’s the opposite.

I went out the other night to a restaurant with my cousin, Nick Pileggi. And I went out with Peter Khoury, a friend on the New York Times, and an actor I know. We all go out once in a while. To the Regency. Maybe to Donohue’s. But now I prefer to stay home and watch the Yankees with Nan. She likes baseball. We watch a lot of television. A lot of movies. And every morning when I wake up with her, I’m so glad she’s still with me. Because when you get old, if you have an old spouse, you worry about who’s going to die first. I want to die first, but I’m not sure I will. And I can’t imagine, after 67 years of marriage, even with our difficulties in those 67 years, being without her.

TMR

Are you still working on the book about your and Nan’s marriage? It’s been anticipated for years.

TALESE

That’s what I’ve been working on. I have photographs from every year of our marriage. What I want to do for the book is pick 67 pictures, one for each year of our marriage. Every year, there should be a picture of us getting older with what happened that year. I have all the notes. In ’59, we got married. The picture is over there, with Irwin Shaw as our best man in Rome. I’m trying to get my daughters to help me. One daughter, Catherine, is a photography editor. I used to hire people for research help. I don’t do that anymore because I don’t want to predict what I’ll be doing the next day. I don’t know how I’ll feel next month. I might be in my robe watching CNN, the news, what’s happening in Russia, Ukraine, whatever. My wife is the same. We live rock star hours now. I live nocturnally like Mick Jagger.

TMR

What’s your nocturnal routine like together?

TALESE

Movies. We’ve seen a million movies. My problem is to find movies that I haven’t seen twice. The New York Times had a list of a hundred movies, but I know most of those.

TMR

What’s on your reading nightstand?

TALESE

I’m in trouble with my eyesight, but I read nonfiction. Such books about writing or magazine writing as Graydon Carter’s. I liked his book. And Michael Grynbaum’s book looks pretty interesting.

TMR

Going back to your book in progress, what has it been like reckoning with your marriage on the page?

TALESE

There were times in our marriage when I wanted a divorce. But none of the affairs I had were marriage-breaking affairs. I never fell in love with anybody except my wife. I was enchanted with certain people, but I never wanted to leave home for those people. I once went to see a psychiatrist through my friend, the Times editor Abe Rosenthal. His early marriage was breaking up. I was complaining one day and he said, Why don’t you talk to my shrink, Peter Neubauer?

I went the first time to see the shrink on 70th and Madison Avenue. It was a big building across from the restaurant that used to be La Goulue. I went into the lobby. I’m here to see Dr. Neubauer, I said. They said, Take that elevator. They closed the elevator to everybody else. Neubauer’s patients were never supposed to see each other. It went directly to the tenth floor. I get to the floor, the elevator door opens, and the guy coming out of Neubauer’s office is Al Pacino. I see Pacino coming out. I’m still in the elevator. He’s waiting to go down. I looked at Pacino, and he looked at me. I walked past him and I thought, What the fuck is he doing here? That guy’s on top of the world!

The receptionist escorted me into the room. Neubauer was sitting in a chair with a cat at his feet. We started talking. He was very expensive. Like $200. It was a lot of money for me then, but I started seeing him. He asked me about my work. I was then writing what would be Unto the Sons about my Italian ancestry. He was very interested in talking about that. We talked about my wife. He said, I’d like to meet your wife. I went home. She knew I was seeing a shrink. She didn’t know exactly why. She saw him. Neubauer fell in love with her. Neubauer told me, Listen, Gay, you’re making a mistake. She is wonderful. I needed that a little bit.

TMR

How common were affairs among your contemporaries?

TALESE

Norman Mailer had six wives. He went to the trouble. You see, Mailer fell out of love and out of liking some of his wives. Stabbed one of them! Even his last wife complained about him seeing other women. Tom Wolfe married very late. Some said he had affairs. I’m not sure. Pete Hamill had a lot of women, including Jackie Onassis and Shirley MacLaine and Linda Ronstadt. He had a Puerto Rican wife, then a Japanese wife. Styron had a lot of affairs. Marriages in the literary game are not long-lasting. Except for me.

I was never out of love with my wife. I was out of liking my wife. Sometimes I was out of liking her a lot. I kept a record of this. I couldn’t believe we survived it, me and Nan. It’s amazing, marriage. Nan really loved me and I loved her. Sometimes not at the same time, though. And I write that. She must have known but she’s stubborn. Nan doesn’t take no for an answer, which I liked about her. I mean, she married me!

I was already seeing Nan when I went to Rome in ’59 to write a piece for the New York Times Magazine about the Via Veneto, where Federico Fellini was shooting La Dolce Vita. The writer Irwin Shaw was also there, and he said, Why don’t you have Nan come to Rome? Nan worked for his publisher. So I called her. She came over with my birth certificate. She had gotten my father to give her my birth certificate. She was ready to get married. I didn’t want to get married. I was worried about losing my freedom. She said, I bought a one-way ticket and if we don’t get married, I’m not going to see you anymore. I didn’t want to lose her. I didn’t want to have her, but I didn’t want to lose her. And I didn’t want anyone else to have her either. I was very possessive. So we got married. Irwin Shaw gave us a fabulous wedding party. Fellini came with his whole cast.

TMR

Let’s keep talking writing. How would you describe nonfiction’s place in the literary canon today?

TALESE

When Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, and Joan Didion were getting published in magazines, I would hear, Salinger’s got a new piece in the New Yorker next week. Norman has this piece on the convention. Tom has got a piece coming in New York magazine. You’d go buy it, soon as you could. We’d hear about it. I don’t hear about it anymore. I don’t know that there’s prestige in magazine writing now that’s comparable.

TMR

Writers of your era could be fiercely competitive with each other. Did you feel competitive?

TALESE

When I met Tom Wolfe, we became friends right away. He started writing for Esquire around the time I did. We shared an editor, Harold Hayes. I was never competitive because I knew you couldn’t compete with Tom Wolfe. He was in a world of his own. His writing was so different. Young people sometimes made the mistake of trying to be like Tom Wolfe. Same with Norman Mailer or Gore Vidal, a very stylistic writer. It was a disaster.

TMR

Did you know Vidal?

TALESE

Yes. In 1993, I did “Don Juan in Hell” at Carnegie Hall. It was a benefit for the Actors Studio, with Norman Mailer as Commander. I played Don Juan, Susan Sontag was Doña Ana, and the Devil was Gore Vidal. What an experience to memorize that stuff. It was very hard.

TMR

How was it dealing with Mailer and Vidal? They were rivals.

TALESE

Maybe they promoted themselves that way. I do believe that Tom Wolfe got under the skin of Norman Mailer and John Irving. Tom Wolfe wrote that the novel was dead, that their novels didn’t get outside their personas and were too insular. They didn’t want him criticizing them. Then that goddamn Tom Wolfe writes a novel and it’s successful. Jesus. He does it. Makes a major bestseller out of it. Courageous guy. So courageous! Tom Wolfe couldn’t even get published today. Writing about the Black Panthers going to Leonard Bernstein’s party? Try to get that published. Who would publish his attack on William Shawn and the New Yorker? How about the Flak Catchers? No way. Maybe “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” wouldn’t be published either. Too long!

TMR

What was New York’s literary scene like back then? Plimpton’s Paris Review parties, were they as rowdy as everyone says they were?

TALESE

They were the preview of Elaine’s restaurant. The people that went to Plimpton’s would later on go to Elaine’s, Plimpton included. You would meet all kinds of riffraff as well as the elegant and the elite: people who went to Harvard, sons of secretaries of state, pimps, cutmen from boxing rings, some drunken musician. Plimpton was a wonderful aristocrat of the people. He wasn’t a social climber. He was a social descender. He went down the ladder. Nobody liked him. I loved him. I knew Plimpton well and got to know him right to his last years on earth. I liked Styron. Styron lived here at the townhouse when he was writing The Confessions of Nat Turner.

TMR

Styron lived here while writing that!

TALESE

Yes, for two years. I wasn’t making much money but with my wife’s job and my job at the Times and my freelance work, I was making enough to support three apartments here. One was empty. He wanted to come in from Roxbury where he lived with his wife and children and needed a pied-à-terre. Nan said, We’ll rent this to you until we need it. Sometimes his wife Rose was here. Sometimes Mike Nichols and Elaine May. He had a lot of fancy friends. Styron was well-connected. He wrote the novel in longhand on yellow lined pads. He’d come down in the evening with these yellow pages of beautiful handwriting and read what he wrote that day. I loved the book.

TMR

Was Styron a good house guest?

TALESE

He was. Rose Styron gave Philip Roth’s first wife the key. Maggie Roth would get drunk and lose her keys and come in at four in the morning. She was really a pain in the ass. And sloppy.

TMR

Did Philip Roth ever come by?

TALESE

They were broken up by then. But through this house, this living room where we are sitting, and that front door came many famous writers. Nan’s writers and my writers. Gabriel García Márquez. Allen Ginsberg. Styron had to give up the apartment because our daughter Pamela was born in ’64. Rose Styron was very mad about it. They both were. We remained friends but it was a little sour.

Between ’61 and ’65, I had written a lot for Esquire. Probably 15 or 20 pieces. The happiest assignment I ever had was Peter O’Toole. He got me to change my life. I went to London to be with him. He had just finished Lawrence of Arabia and I loved it. He interviewed me! Tell me about your wife. Do you have any children? This was in ’63. No, no children. I don’t have any money. He said, You’re not a risk-taker! I’m an actor, I have a three-year-old daughter, and I didn’t have any money until this last film. Why don’t you have your wife come and stay a couple days?

Peter O’Toole and his wife Siân Phillips, an actress, had a house in the Hampstead section of London. They had a guest room. I called Nan. She flew over for the weekend. We got pregnant in Peter O’Toole’s guest room.

TMR

Speaking of the next generation, you’ve had quite the youth resurgence this year. Young writers packed McNally Jackson Seaport and Rizzoli at readings celebrating A Town Without Time. The Times reporter Alex Vadukul wrote that collection’s introduction. Your “Love/Hate List” with Dream Baby Press went viral. How do you feel about us all taking a shine to your work?

TALESE

I didn’t know that list went viral. You see, I’m a mid-20th century guy. I’m stuck in the ’50s. The way I work now is the way I did in 1955. But I love young writers. I was a young writer and people held me. On the Times there used to be a famous elder journalist, Meyer Berger, who had a city column called “About New York.” He was a Pulitzer Prize winner. In my first article as a copy boy, I wrote about the man who operated the Times Square news ticker. I showed it to Meyer Berger. He edited it and they got it published. I didn’t have my name on it, but they were nice to me. Irwin Shaw was nice to me. I was a nobody!

TMR

Who would you say is carrying the torch of city writing today?

TALESE

Alex Vadukul is. And Dan Barry. He’s still the top writer at the Times. He’s not my generation, but he’s really senior.

TMR

You were born during the Great Depression. What was it like growing up Talese?

TALESE

I was born in 1932. What I remember about the Depression is what my parents told me and to a degree what I observed as a child. My father was a tailor and my mother had a dress shop on Asbury Avenue, the main avenue of Ocean City. There was a barter system of trading something of equal value at the store. My mother would sell a dress to somebody and we kept an account of it all somewhere. They got through the Depression.

I certainly remember the war years. The lights on the ocean side of the boardwalk were dim blackout lights, so that the shore was not visible from Nazi submarines that might be in the Atlantic Ocean somewhere. I remember the rationing. The Yankees couldn’t go to Florida because of gas rationing and other things, so they trained in nearby Atlantic City. I got hooked on the Yankees. When I was a high school student, I wrote a column for the Sentinel-Ledger newspaper. I was always curious about what wasn’t newsworthy. I discovered my own stories. Everybody has a story. You just have to find it.

TMR

As a budding reporter, what were you like?

TALESE

I was always showing up and befriending the people I wrote about. I never wrote hatchet jobs, whether for a newspaper or magazine. I never would hang around people I disrespected. It’s too hard to write well. It would be impossible to write about somebody well if you didn’t like them at all. I think back a lot, but I don’t think of myself as changed except by ailments that restrict me now. As for how I live and operate, it’s the same now as it was when I first became a copy boy for the Times in 1953. I like knowing people. I like asking questions. I ask questions in a way that would never suggest gossip. They suggest a sincere interest because I have a sincere interest. A lot of journalists are very purposeful. They have a story, they want you, then they don’t want you anymore. They got their story. But I always go back. I like to revisit stories after I finish them, as I did for Floyd Patterson and the men of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.

TMR

Was there an editor who meant a lot to you as a young journalist?

TALESE

I was not very appreciated at the Times before Abe Rosenthal became the editor. People thought I was making up stories. I was accused of writing fiction. I was going to quit, but I heard he was coming and stayed two more years. Good years. I had big stories with him. My last was going to Selma. I was there when the Alabama State Police and the Sheriff’s posse attacked the civil rights marchers on Bloody Sunday.

TMR

Was there ever a piece that you, Gay Talese, couldn’t get published?

TALESE

I went off to China for a story that never worked out. It was 1999 and the American women’s national soccer team had gone to the World Cup to play the Chinese national team at the Rose Bowl. I was watching it on television from my Ocean City summer house. I don’t even understand soccer, but the game ended in a tie, and in soccer you have penalty kicks. Everybody made the penalty kicks except for one Chinese player, Liu Ying. Here was a woman who blew the penalty kick for a nation of a billion people and she did it on television. Everybody saw her. What was it like to be this woman blowing it to the all-dreaded Americans? American relations were worse with China than they are now. I thought it was a good story, so I flew to Beijing. Maybe it was whimsical, but I went. I spent the next six months with her. Nobody wanted to publish it. I published part of it in A Writer’s Life. That book is a published book about not getting published. A book of all my disasters.

TMR

If you were doing your fabled sports profiles with the athletes of today, how would you approach them? They are kind of mysterious, remote people. Someone like Aaron Judge.

TALESE

I wouldn’t write about him at all. I’d write about Judge’s childhood. How he grew up, his parents’ marriage, what personal adversities he overcame. I would want to talk to his family and then write about his boyhood. That would be the story.

TMR

You did many, many pieces on the boxer Floyd Patterson. What pulled you to him?

TALESE

My first job on the Times when I got to be a reporter and no longer a copy boy was in the sports department. I wasn’t a beat writer, but a feature writer. Patterson was the rising heavyweight at the time. I liked to go to the fights. I never saw a fight until I got to the sports desk, but he was an interesting guy. It was very sad. He shouldn’t have been a heavyweight at all. He was small. A light heavyweight fighter, really. He took a lot of beating but always came back for more. He was a courageous man. A nice person. I admired him greatly. When I did the Esquire piece, I wrote about how he couldn’t protect his daughters from racial taunts at their school. That’s an important scene. We didn’t quite know how to handle it. He was a very conflicted person, but a very interesting person.

TMR

What was it like to go from Patterson to tackling Joe DiMaggio, a man at the pinnacle of the world? Did your approach change?

TALESE

DiMaggio didn’t talk to me at first. I went to San Francisco with the understanding that he would talk to me. Ernie Sisto, a photographer for the Times, had introduced me to DiMaggio in the locker room at an Old-Timers’ Day game. I said, I’d like to go out and see you. He said, Sure, sure. So I didn’t bother writing to him. I just showed up about a month later. I went to his restaurant. In that opening scene in the Esquire piece, he didn’t want to see me. He forgot that he’d said okay, and I kind of overinterpreted it. When I was a copy boy, a reporter told me, Show up! Don’t use the phone! Just show up! You dress well, you’re polite, you get in. I believe that in 2025, that still matters. Whether you are a fireman, an ironworker, or the CEO of some bank. A lot of reporters don’t dress well.

So that’s the Joe DiMaggio story. I never quite got back to him. That last scene was of him at batting practice. Those scenes, like Floyd Patterson running down the road on a lonely morning, are what can make a magazine piece a short story. And that’s what I always wanted. I wanted to be a fiction writer who wrote nonfiction. A short story writer. Because the writers who appealed to me were never writers of nonfiction. John O’Hara, Carson McCullers, Mary McCarthy, Fitzgerald, Hemingway. I wanted to take the short story into the newspaper column. And so I did. Tom Wolfe once said that my Esquire piece “Joe Louis: The King As a Middle-Aged Man” could be a short story.

TMR

Your New Journalism contemporaries wrote novels. You did not. Did you ever think of doing a novel?

TALESE

One time, in 1966, I wrote a short story that was later published in Mademoiselle. It was called “Getting Even.” The big fiction editor wrote my agent, Oh, we love this, we’re going to use it, can we get more from him? But I was then also writing those pieces about DiMaggio and Sinatra. I didn’t want to be just another fiction writer. There are so many good fiction writers. Why would I want to be another one?

TMR

You once mentioned in an interview that you thought Donald Trump learned a lot from George Steinbrenner. How do you think Trump was influenced by Steinbrenner?

TALESE

Well, I was there. I saw it. I would often go to Yankees games in Steinbrenner’s box. It became a routine. Sixty people could be in that box. Real estate people, rich people, prominent people. And one of them was Donald Trump. I met him a number of times. He knew that I lived in the East 60s. And oftentimes, he’d leave the game around seven. He always left before the game was over. He’d say, You want a ride downtown? I got a ride with him many times downtown. He’d drop me off here to go on to 57th Street.

And then I’m from Ocean City, New Jersey. Donald Trump was very big in Atlantic City. He said, You ought to go down and look. I do these casinos. So when I would see my parents, I would go to Atlantic City. His wife Ivana was running one of them. She showed me around. She was very nice to me. Sometimes Trump would come down. I don’t gamble but I would go to the casino for dinner, which I insisted on paying for because I didn’t want to be in with anybody.

I noticed the way Steinbrenner ran the Yankees. Firing Billy Martin, hiring Billy Martin, firing Billy Martin. Being “the Boss.” Taking an interest in everything. A detail man. So was it that I noticed how much Donald Trump seemed to be attracted to, hanging around, talking to Steinbrenner a lot. And I thought, This is like his father. The father that he liked, rather than the gruesome Fred. So I’ve always thought Trump went on to run the country like Steinbrenner ran the Yankees.

TMR

Did Trump ever cross your mind as a possible Talese profile?

TALESE

I didn’t want to write about famous people. I wasted a year and a half in the early ’80s working on a book about the Ford and Chrysler automaker Lee Iacocca. He was on top of the world. I met him through Steinbrenner. Iacocca was in that box when he was in New York. Iacocca said, Why don’t you come out and see our Chrysler plant? And I did. It was a good story. Cars were a different world for me. He was Italian American, as I am. And he was so cooperative. He let me stay at his house in Michigan. I met his wife and daughters. I traveled with him on his plane when he went to advertising meetings and meetings with the secretary of the Treasury when he was trying to get a government loan to bail out Chrysler. But in confidence he would say things to me, and in the press he would say something else. I didn’t want to write a biography, but he was so nice to me that I didn’t know how to get out of it.

At the same time, my best friend David Halberstam thought he would write about Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler. David said, Do you mind if I start interviewing Iacocca? In a way, I didn’t mind. But in a way, I did. I didn’t want to give up. I said, Let’s both not do it. He said, No, I’m going to do it. He was so competitive. That broke us up for ten years. Then Iacocca got an offer from some ghostwriter. That’s how I got out of it. I decided to go to Italy to write Unto The Sons about my own father rather than Iacocca. I wanted to write about myself for a change. I didn’t want to be famous, but I wanted to be known to myself.

TMR

Speaking of fame and obscurity, when you were 25, you wrote about the secret lives of the city’s alley cats. What drew you to street cats of all things?

TALESE

That was my first front-of-the-book story for the New York Times Magazine. It was 1957. I had read a collection of stories in the New Yorker by Joe Mitchell some years before. Joe Mitchell wrote a story in the World War II period about rats. It’s a wonderful piece. And I thought, Rats! Well, I’ll write about cats. So I stole from Joe Mitchell, one of the few nonfiction writers that I read. I didn’t like his long dialogue passages, though. Mitchell, I thought, was faking quotes. Nobody talked like that. He was like a tape recorder before the tape recorder. Those people on the waterfront didn’t talk that way. But I liked his writing.

TMR

Your most humanistic work might be The Bridge, which is filled with tales of the hard and anonymous men who built the Verrazzano-Narrows. What was it like reporting it? There’s that picture of you in the hard hat.

TALESE

I loved that story. Of course, I dealt with the man on top, the engineer O. H. Ammann. He had an apartment many stories up at the Carlyle Hotel. With binoculars, he’d look at his bridges from up there. A wonderful guy. I met the ironworkers. Eddie Iannielli was one who helped me. I got to know them all. I went to the union, met the shop steward, and I got permission from U.S. Steel to go up on the bridge. They gave me the hard hat. I was always accompanied by someone from the company. They didn’t want me to fall off the bridge. But I went onto the catwalk with those men.

TMR

Did you ever meet Robert Moses?

TALESE

When the bridge opened, I was standing next to Moses for a while. He was the host. During the announcement, he didn’t even mention my name or Mr. Ammann. It was his bridge.

TMR

How did you start writing the book?

TALESE

It started out as a Times assignment about people protesting Moses. I went out there and I thought, Jesus, this is like a war, and people are going to get moved from this area. Like they bombed Hiroshima, it was blown out. Then I wrote an article about Mr. Ammann. Then another article about an ironworker named Hard-Nosed Murphy. I started to see a book. When I had time off on the weekend, I’d drive out there and see people. I’d sometimes take days off to go out there and watch them build the bridge. I watched every stage of that bridge. Half up, fully up. I was part of that work. I know those people. I love those people. In a way, it’s probably the most meaningful reporting I’ve done, since it’s a history that only I saw. When I would drive across from Staten Island to Brooklyn, my little girls would say, That’s Daddy’s bridge! For a while they thought I owned it. I didn’t tell them until much later.

TMR

We actually brought a first edition of The Bridge with us. We hoped you could sign it.

TALESE

Boy, oh boy.

TMR

It’s great because you’re on the back cover. They tell you how old you are.

TALESE

How old am I?

TMR

They say you’re 32. One of the finest young writers in the newspaper business. And you’re married, with a wife and daughter.

TALESE

32!

Ross Barkan is Editor-in-Chief of The Metropolitan Review.

Lou Bahet is Executive Editor of The Metropolitan Review.

This is incredible. I'm always curious about how much cleanup goes into an exchange like this one but, having coincidentally just spent a few days bingeing Talese's interviews from the past five years or so, I'm inclined to think he just talks this way. Neat paragraphs, stories within stories and all of them tying up. But I particularly loved the question about having nine decades inside him. All those faces and names. The Styrons and Pacinos walking on and off the stage of his memory. This is transcendent, guys, congrats (and kudos)!

Good God, (swoons)... This is the most remarkable interview I’ve read all year. The old-school magazine nerd in me longs for it to be bound and glossy, with full-bleed portraits and a whiff of ink that says, man, this was when writing still had swagger. Seriously iconic.