Seth Rogen is dreaming of New Hollywood. Just a few weeks ago, Apple’s The Studio won 13 Emmys — setting the record for most wins for a comedy series. The cynical read on this would be that there’s nothing Hollywood loves more than another backstage satire about itself; such an avalanche of golden trophies is as much a marker of the movie business’ self-love as it is for any qualities of the show, which are plenty. Certainly, The Studio is no Sunset Boulevard — no pitch-black excoriation of the underbelly of the world’s glitziest exploitation land, nor some more highly wrought tragic riff on a dying medium. Still, Rogen’s show has the distinction of being the first contemporary piece of media to depict the process behind the movie industry as it is right now — and to actually say something about it.

The first of these things that The Studio says, it says quite literally — buried in an exchange between soon-to-be-head of the fictional Continental Studios, Matt Remick (Rogen), and his assistant Quinn Hackett (Chase Sui Wonders, one of the first great actresses in years who could genuinely play a ’30s screwball comedienne). In the first minutes of the first episode, Remick reveals he has to take meetings with representatives from both Rubik’s Cube and Jenga. One of the funnier through lines in the show is Continental’s desperate attempt to find IP comparable to Barbie, though Remick would rather be making something truly prestigious:

Quinn: Oh my god, this is so depressing. I’m like, 30 years too late to this fucking industry.

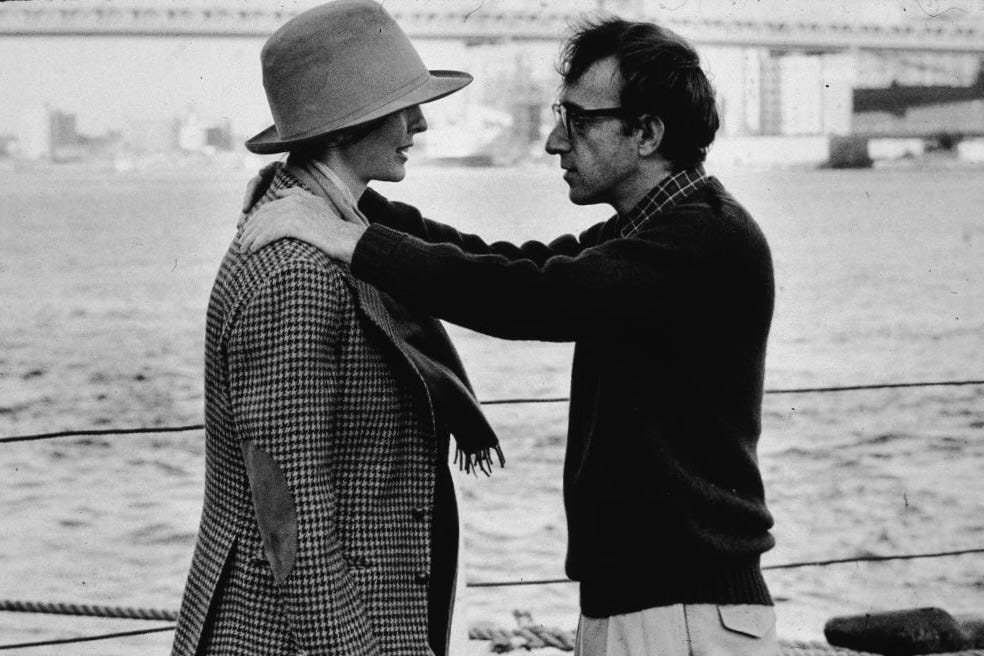

Matt: I know, trust me, if it was up to me, we’d be focusing on making the next Rosemary’s Baby or Annie Hall or, you know, some great film that wasn’t directed by a fuckin’ pervert.

Quinn: Turns out perverts make great movies.

Matt: They really do.

It’s chuckle-worthy, and those two titles are really picked more for their famously loathsome directors than as proper stand-ins for their period. Yet, it’s still clear that what’s on Remick’s mind is the same thing that seems to be on many minds these days: that grand romantic lost world of New Hollywood, the final glory days stretching across the late 1960s and ’70s, when every year Hollywood seemed to mint future classics pitched to actual adult audiences — days when a film like The Godfather might be considered serious movie art, top the box office, and still win a bevy of Oscars on top of it all.

In the episode, Remick soon gets his promotion, yet when he walks into a meeting with his new boss, intent on selling his idea that prestige and box office results ought to be reconciled, he walks out instead with a single bottom line: making a tent-pole film out of Kool-Aid. And so, many antics throughout later episodes will center around Remick’s attempts to be taken seriously as a “filmmaker” while having to hawk superhero movies, cast IP cash-ins, and avoid being bought by Amazon, fucking over real filmmakers like Martin Scorsese along the way. Dozens of celebrities come and go, playing themselves, and the show does a fine job of skewering awards shows and Comic Con reveals, along with the general, ambient sense that movie studios these days seem to investors like outdated appendages of tech companies.

In what’s probably the show’s best episode, “The War,” Quinn and her co-executive Sal Saperstein (Ike Barinholtz) sabotage each other’s projects in increasingly spiteful ways. Sal wants to hire the actual director of Smile to make a clear rip-off, called Wink. Quinn wants to bring in Owen Kline — a young director with a single small A24 film that went to Cannes, which she pitches to Remick as being “executive produced by the Safdie brothers.” Of course, the prestige-coveting Remick loves the twinkling sound of the Safdies, A24, and Cannes — but slick old Hollywood Sal declares Wink is for normal people, not “pansexual mixologists living in Bed-Stuy.” When Sal accidentally destroys a movie set with a poorly lobbed burrito, Quinn openly celebrates how easy it would be to get him fired: “I’m technically a bit of a minority. A bit of a woman of color. So you’re double fucked. I’m gonna be a hero! There’s gonna be marches in my name!” It’s a good, healthy sign that a TV show can finally make light of these kinds of things.

The Studio gets all its details right, gives us what I imagine is a painfully accurate image of the contemporary foibles and essential vapidity of Hollywood — it’s perfectly funny, very well made, sweetly nostalgic, and dead on with its skewering. It’s the kind of thing 10,000 critics have surely declared, “A HILARIOUS HEARTFELT LOVE LETTER TO THE MOVIES.” And it was surely some murky combo of this sentiment and its genuinely pointed satire that managed to bag it so many Emmys. But in the end, the thing that the show cannot quite escape is just what haunted it from that first exchange: the glory days of the medium are gone, never to return. Studios are locked in a battle against their own capitalistic decay; it’s never been harder to get masses of people to sit down for a film; and the stuff we do make on any big scale has never been stupider, or more infantile. O New New Hollywood, where art thou?

But let’s rewind briefly to those films mentioned in Quinn and Matt’s exchange. Are these pervert-made classics really the exemplary films of their period? In subtle ways, yes. In 1968, Rosemary’s Baby was a landmark horror film that did spectacularly well at the box office and made Roman Polanski’s American career. Our memories of the ’60s are peculiar and selective: this was a major studio movie based on a popular book. In fact, it would probably shock modern audiences to realize just how many stories now remembered as classic Hollywood films were adaptations of novels nobody knows anymore. But it was resolutely a mainstream effort. The studios were not gone in the late ’60s, replaced by fervent young filmmakers or swamped by the counterculture. No, the studios were made of old heads, old movie people, attempting to respond to rapid changes in temperament, and the freedom offered by the termination of the Hays Code.

So consider Annie Hall, from 1977 — a pop classic if there ever was one. It may take another generation before we remember what a genuinely great filmmaker and comedian Allen actually was, but even today Annie Hall is the one film even Allen haters can’t really deny. It’s the film that beat Star Wars at the Oscars, after all — and probably deserved to. But more than anything, Annie Hall has next to nothing to do with the spirit of the New Hollywood of popular imagination: what it shares is the abstract ethos of a time in which artists were supposedly given money and freedom to do as they wished; while, somehow, many of these films ended up becoming popular, lasting, memorable hits. So though it’s haunting our memories and minds these days, New Hollywood was much more vague than we sometimes realize. It certainly wasn’t some radical vanguard of outsiders — it happened firmly under the green lights of the old guard. And besides, there was virtually nothing to been seen in Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, The Godfather, Cabaret, Chinatown, or Taxi Driver (to name the most-named) that can’t be pretty handily traced back to their influences in the French New Wave, alongside postwar Italian, Swedish, Polish, Czech, and Japanese cinema. What it was, was a vibe. “We can do this kind of thing now,” said the studios and filmmakers of the time, and audiences believed them.

More than one commentarian has suggested that our time resembles the rise of that moment. Our streaming TV wasteland is comparable to the first popularization of television in the ’50s, while the tremor that sent through Hollywood — leading to the revamping of the star system, huge roadshow musicals, sword-and-sandal epics, and Oscar-winning spectacles like Around the World in 80 Days — can surely be likened to our contemporary studios’ reliance on sequels, reboots, comic book characters, and other recognizable IP. If there’s one reliably successful thing we make cheaply and en masse these days, it’s surely horror films — and these might find their analogue in the old ubiquitous, cheap westerns. If we insist on any kind of rigid 1:1 ratio, historically, then we should be in for a similar revitalization of the cinema coming, well, just about anytime now. Maybe next year, or maybe the next. So some have been saying, for a while. So some keep trying to say . . .

With the remarkable success of Warner Brothers this year, prophecies of the coming New New Hollywood have grown only more frequent. To be fair, the success is pretty dramatic: seven films in a row opening at over $40 million — A Minecraft Movie, Sinners, Final Destination Bloodlines, F1 the Movie, Superman, Weapons, and The Conjuring: Last Rites — a streak only broken by everybody’s beloved One Battle After Another. (There are limits, and apparently a film by the greatest working American director is one of them.) Warner Brothers crossed $4 billion worldwide with just 11 films, and the last time they did that, in 2019, it took 20. Considering the other big films of the year, there’s the supreme zombie indices of Jurassic World Rebirth, and Disney’s biggest hits, which were both live-action retreads, How to Train Your Dragon and Lilo & Stitch, while Marvel flunked with Thunderbolts* and just barely made up for it with The Fantastic Four: First Steps. The final Mission: Impossible did well enough to crack the top 10 of the year so far, but the gold medal goes to Ne Zha, the Chinese juggernaut, distributed by A24 in the States. With Zootopia 2, Avatar: Fire and Ash, and Wicked: For Good still to come, forecasters predict this might be the best overall box office year since before the pandemic. I can only nod and agree that this is a generally good thing, and I hope that it’s as promising as many are saying it is.

And yet look at those films. I love a good popcorn movie as much as the next person, but I’m going to stake my flag on Snob Island here — since I think we’re certainly not going to get closer to any kind of cinematic renaissance by cowering from charges of elitism — and say that almost none of these are films for intelligent adults. Most are for children, or adults who need to feel like children.

Now, for a slight comparison, consider the ten highest-grossing films of 1968:

Funny Girl

2001: A Space Odyssey

The Odd Couple

Bullitt

Oliver!

Planet of the Apes

Rosemary’s Baby

Romeo and Juliet

Yours, Mine and Ours

The Lion in Winter

This is, frankly, so embarrassing we should be crawling under our beds and crying ourselves to sleep. By my count, that’s one classic musical (1) and one decent one (5), a classic comedy (3), a classic action film (4), a classic sci-fi (6), a classic horror (7), one of the great Shakespearean adaptations (8), and two of the best films ever made (2, 10). Only one of these films has been mostly forgotten by time, while the others still make the rounds on YouTube reaction channels as “essential classics” for even the most internet-brained content creators. And crucially, none of these are really your stereotypical “New Hollywood” films (even 2001 was a colossal MGM spectacle on paper). Funny Girl is so old-school it was directed by William Wyler. Bullitt and Rosemary’s Baby do have that “New” flavor — both in camera technique and subject matter, but they exist far, far away from the counterculture. Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet made waves for marketing Shakespeare as a “youth movement” picture, but it’s really an Italian film made with American dollars. The Lion in Winter is a dense historical drama with one of the most literate and sophisticated scripts ever adapted from a middling stage play. I repeat: put up this year’s big films — are any of them anywhere near this level of essential artistry?

I admit I depart from nearly everyone on Sinners — it’s a fun ’90s romp disguised as a post-2010s social issue picture. It’s also not very good; it only has the trappings of a style. Weapons at least is well made, and its creepy allegory is potent — it especially seems to signal the ways in which “elevated horror” is tapped out, and Cregger’s half-comedic dream-space approach feels like a relief after a decade of exhaustive, obvious ideological critique. Superman and The Fantastic Four: First Steps are most notable for being deliberate throwbacks, attempting to remind their audiences of the days when superhero films felt just a bit less impersonal and gray, and it didn’t require too much familiarity with the universe or its tie-ins to be legible. As I’ve written before, this also signals at least a slight shift. But I’m unconvinced of any larger movement. The two ostensibly “adult-friendly” films I’ve seen talked about most — Materialists and Eddington — were not successes. And though both have interesting, conflicting things to say about what our society is actually like these days, both are finally undermined by the fact that “saying something about what our society is actually like these days” is their governing principle as films. Both struggle to just be works of art, and lose themselves in textual commentary on themselves and their positions in contemporary discourse.

No, I’m sorry to say, I see no reason to hope that an uptick in box-office success will equate to an uptick in cinematic art. There are, of course, brilliant films being made all the time (consider how both our great American Andersons turned out all-time great Benicio Del Toro vehicles this year). But like Matt Remick walking out of that first episode’s meeting, the triumphant hope that box office and prestige might once again meet in the minds of the masses is still being beaten over the head by the brute fact that what most people seem to want is the same: slop, slop with stars, slop with capes, slop with the Disney logo on it, slop you can share with the whole family.

New Hollywood emerged for two big reasons: (1) There was something to draw on — namely the fervor induced by beautiful European women walking across the modernist compositions of European geniuses, and (2) a true movie-going culture. In the years when the ’60s cultural shift hit cinemas, movies were already the central cultural pastime. Tickets were cheap. People came in and out of the theater as they wanted. Sometimes people watched two films in a row, or stayed in their seats to watch the same film again. Sometimes they caught the second half and stayed around after to catch the first. People might stumble into a film they’d never heard of because the title sounded interesting or because they were bored. Plus, there was air conditioning in the summer and heating in the winter. If we can’t ever recapture that world, even in miniature, what good is there of dreaming of another New Hollywood?

This sounds like pessimism. But it’s not — it’s reality. There are steps that have to be taken if movie culture is to become dynamic again. This is arguably possible; it’s just not going to look like a revival of the last time popular movies suddenly grew important and exciting. Audiences have to be prepared to think, to want to think, about the things they are seeing. Executives have to be willing to take risks. And this is going to sound rather harsh, but independent filmmakers are going to have to get better. (And I don’t mean A24 or Neon, which are more brands than studios by now, and increasingly dull ones at that). I mean actual independents. Local communities and artists alike should be religiously, zealously aspiring to make great art on their own, even within their limited means. And people need to be brutally honest when even the most sympathetic young artist makes something that isn’t very good. Inflated praise is a disease of our time, and there’s no crying in baseball.

But of course, more than anything, critics have to start acting like critics — no longer lobbing soft two-star reviews at the latest Minecraft movie or condescending to review the dregs of streaming offerings. They have to champion the films that really are that great. In the last five or six years, I’ve seen numerous films that deserve to be called future classics: the Safdie’s Uncut Gems, Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu and The Lighthouse, Joanna Hogg’s Souvenir films, great middle-period films from P.T.A. and Wes Anderson, Aki Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves, Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World, Noah Baumbach’s White Noise, and Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. Not one of these films is too obscure or dense or too demanding for most audiences. Each one is entertaining, beautifully made, and — crucially — intelligent. These are the kinds of films that ought to be reaching huge numbers of people, winning awards, and dominating the box office. Part of what has made One Battle After Another so interesting is that it seems to be the rare moment in which something like that is very nearly happening.

And yet one film does not a zeitgeist make. The worst of cinema’s nadirs may be behind us, but that does not mean the road ahead will operate in ways predictable by any study of historical change. If anything, we ought to be going back to the films that inspired that original New Hollywood movement: the French New Wave, the great postwar world cinema masters of the ’50s and ’60s — films that are, if anything, incredibly undervalued these days. But like all incredibly fertile periods in art, their fertility is fairly endless. One more viewing of Jules and Jim, or Cleo from 5 to 7 — a trawl back through The Leopard, or L’Avventura, or Ivan’s Childhood, or the films of Bergman, Ozu, Kurosawa, the best of the Czech New Wave — could mean all the difference. Anything to keep from dreaming the same Matt Remick dreams, the same suckling sadness of the loss of a faded Hollywood, fantasizing about the next Godfather that could achieve that holy triumvirate of cinematic blessings: money, praise, and statues. Instead looking — peering back — for something, anything, to remind us again of what really makes things new: real experiment, real urgency, real flash, or ingenuity. For the sake of the art, and barely tolerating commerce, not a dream of a lost novelty, but a proper understanding of the source from which the new once came. That alone will do.

Sam Jennings, The Metropolitan Review’s film critic, is an American writer living in London. He is the Poetry Editor at The Hinternet, and he runs his own Substack, Vita Contemplativa. For those interested, his Letterboxd account can be found here.

Enjoyed this very much. There used to be movie people, storytellers, actual creative people in movie making. I’m not sure how many of those exist in studios anymore. Today’s’ suits make yesterday’s suits look like cosplay fanboys.

Good piece though I cannot cosign sneaking the White Noise adaptation into that list. I thought about this sort of thing when I was leaving One Battle After Another. Whenever I see a really good and entertaining new movie like that I always leave the theater happy but it's tempered with a feeling of... hang on, we can still do this? Why aren't we doing it all the time??