When it’s time for lunch, the old men strut naked to the cold showers for a rinse. Their hot, bony feet, arches flattened by the tonnage of fat knees, are somehow immune to athlete’s foot or whatever virus crawls in the bathy fray. Disease lives on the wood slabs of the sauna, in the cracks of broken shower floors, between the toes of barrel-chested men who somehow can’t contract Giardia. Aging bodies roast silently in gold jewelry they refuse to take off, chest hair singeing under six-pointed stars and Chais, little pinkies burning too. Inside these perspiring men are cold operators, and to be shamelessly naked is the Yiddish art of war. Welcome to Jason Diamond’s debut novel, Kaplan’s Plot, set in a Chicago underworld where business is done in the shvitz. Where you know that no one’s wearing a wire.

The novel alternates between two storylines, one set in the early 20th century, the other in the present day. In the earlier timeline, like the Muppet vampire Count von Count, Diamond gorges on a Jew-Fellas version of his ancestors’ coming-to-America past while keeping a jocular tone. The clock is set to 1911, and hordes of Yiddish-speaking Jews arrive from the East with tragic pasts, desperate for work, calling on distant relatives for a room or a job. Diamond’s characters, two brothers, Sol and Yitz Kaplan — the sons of a butcher, separated from their parents — chase a distant family connection to Chicago, where their sister might be. It’s a story we know well: Jewish mobsters with flashes of idiosyncratic, Borscht Belt-y asides and the reluctant goodness of self-made men. But Kaplan’s Plot, apart from a few brutal flashes, avoids the tragic motifs one associates with the immigrant world. When a kitchen knife penetrates the skull of a homicidal Ukrainian intruder, an old Jewish woman can always be counted on to mutter that it was her “good knife” and, next time, use a different blade. Diamond’s prose is loose and playful, more concerned with funny character details — like when Jerry the Fox, an old Jewish man, says “l’chaim” before taking a sip of decaf — than with proving a writer’s mastery of the cityscape. His Chicago is less severe than Michael Mann’s merciless downtown in Thief, less savage than Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.

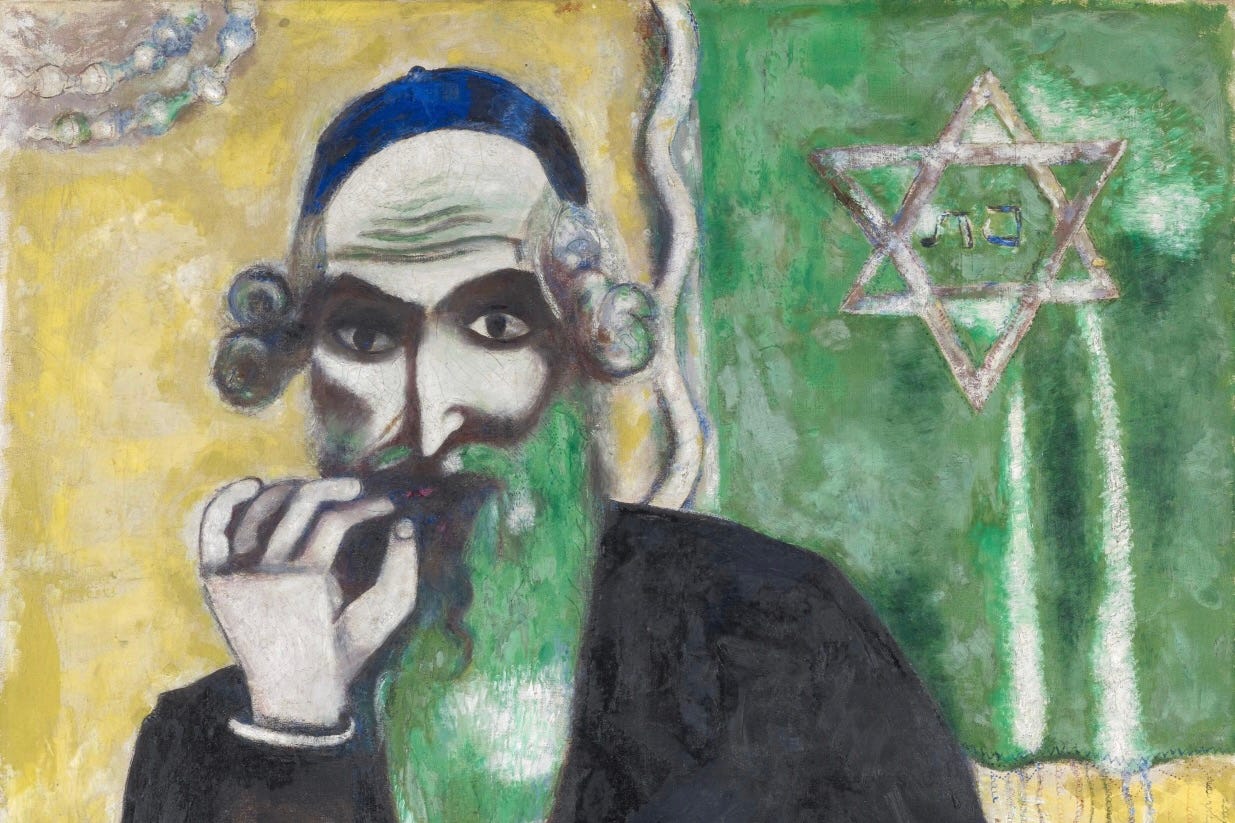

Sol and Yitz’s origins in America are not so different from Vito Corleone in The Godfather Part II or László Tóth in The Brutalist: young men washed ashore with nothing, elbowing through the pukey decks to Ellis Island. When the ship docks, Yitz overhears Hershey, their nervous guide, muttering, “God laughs while men make plans,” the conversational version of the old Yiddish adage. It’s no coincidence that Yitz, the Cain to his brother’s Abel, is the one to hear it. Diamond plants this early, and keeps the pages turning with the question of which brother will go what way. Who is Sonny and who is Michael? Neither has Fredo’s tragic firstling incompetence. Regardless, the pull of assimilation and retribution is strong, and each brother must exchange innocence in the name of self-preservation. Perhaps being an American means frisbeeing one’s yarmulke into the Atlantic. Diamond is quick to underline the otherness of the Hasidim on the boat, sequestered in a corner, praying alone. In the old country, their sidelocks and shuckling were ordinary; in the New World, they are freakish. This version of the Midwest suggests that tradition belongs in the past, along with submission.

Diamond’s turn-of-the-century narrative offers firmer moral ground than the second, contemporary story. The past gives us Jewish underdogism and victimhood that can be redeemed by tenacity, loyalty, and other homespun virtues. The present day, for Diamond, requires navigating a murkier existential drama. As Diamond bobs and weaves through three generations of Kaplans, the book thrives when the stakes are clear — when killing is an accepted mode of deterrence. That’s no longer true by the time we arrive at Elijah Mendes, Yitz’s grandson. His relationship with his mother, Eve — a dying, vape-addicted literary figure — is strained. Eve is a cold academic type who initials the notes she leaves for her son around the house. Elijah is a failed tech bro, back in Chicago with his tail between his legs after years in Silicon Valley. Assimilated to the point of mistaking religious Jews for Amish, he knows nothing of Orthodox Judaism or what drove his ancestors to keep a lid on the past. That begins to change when a letter arrives directing him to a family burial plot. As he learns of his grandfather’s brutality and the gold buried in the family mausoleum, his sense of the world becomes even more confused. Elijah is aimless and morally compromised, a man without interests beyond making a quick buck. It is refreshing that the narrative does not take on technology in an obvious way. It is a given that Elijah is a phone addict like anyone else in 2025. Rather than tell us directly, we learn that Elijah’s own mother would rather share her writing with his friend than with her own son. To Eve, her son is the hollowed-out Jew two generations removed from the triumphs fought for and won by their ancestors.

Kaplan’s Plot is not a thriller, but its most affecting moments are between the brothers Sol and Yitz as their roles diverge. We are led to believe that Sol is the good one — moral, religious, a butcher like their father, thick as a barrel but gentle. Yitz accepts violence, quick to argue that retribution is a necessary tool for Jewish survival. But when Sol dies as a result of Yitz’s vague business miscalculation, we learn that Sol, despite appearances, got his hands dirty too. As Diamond would have it, everyone did.

Yitz embraces brutality as a necessary tool for Jewish survival in a world surrounded by enemies — Poles, Irish, Italians. If Diamond is an apologist for Yitz, it’s painted in light tones, as if to say, “You gotta do what you gotta do.” When a fire in Jewtown burns down several buildings without killing anyone, Diamond directs our attention to “Jewish Lighting,” a slur suggesting Jews torched their own property for the insurance money. There’s an old joke: “Moishe, I’m so sorry to hear your house burned down.” Moishe answers: “Shhh. It’s tomorrow.” Diamond has a way of glorifying or romanticizing the bad but necessary things that defined a vital Jewish past.

Diamond’s prolific social media presence — a tribute to vintage Jewish masculinity (why isn’t that a Netflix category?) — oscillates like his book: mob-era nostalgia, still shots of Sam “Ace” Rothstein, praise for Hyman Roth’s languid, towel-wrapped body in The Godfather Part II. If there’s one thing Diamond likes, it’s shoulder hair, especially if it’s grey and greased with sweat. Almost like a scene from his Instagram, Yitz sets up shop in the shvitz, which back then wasn’t the cliché it is now, thanks to sales-y Wall Street Journal articles, Substack bathhouse readings, and Netflix shows like Black Rabbit, where deaf mob bosses hold court under the hot pipes of the Ninth Street baths. Diamond has been hawking the bathhouse “scene” as both date spot and male bonding ritual for years. There are plenty of pictures of the author in tight T-shirts and shvitz attire — any Aufgussmeister would recognize his physique as the “ideal sauna body”: husky, hairy, thick-limbed. But the shvitz, as a place of business, a spot for a certain kind of man to escape his wife, is the timbre of Diamond’s nostalgic Jewish masculinity both online and in Kaplan’s Plot.

If it was Diamond’s aim to codify the past while leaving the present pallid and meandering, point taken. Jews still cling tightly to a past where the moral lines were sharper. It was a time when everyone could agree that an immigrant’s journey is a hard one, and sometimes you gotta break some eggs to make an omelette. No wonder films exploring the same themes, like Jesse Eisenberg’s A Real Pain, emphasize the emptiness of modern Jewish protagonists who can only feel when they brush up against tragedy. As Jason Diamond’s Instagram suggests, the modern American Jew’s journey is often a kind of dress-up: a night at the shvitz in memory of their grandfather, a sultry bathhouse selfie in a banya cap. The same pierogies, the same rivers of borscht flowing like the salmon of Capistrano. But why?

Noah Rinsky is the creator of @oldjewishmen and the author of the bestselling humor book, The Old Jewish Men’s Guide to Eating, Sleeping, and Futzing Around. His personal Substack is Father’s Milk.

It's true: I do love shoulder hair. Thank you for this thoughtful review.

Well done...thank you!