The Power of Art in the AI Age

On 21st-Century Painting and the Backlash Against the Thinking Machines

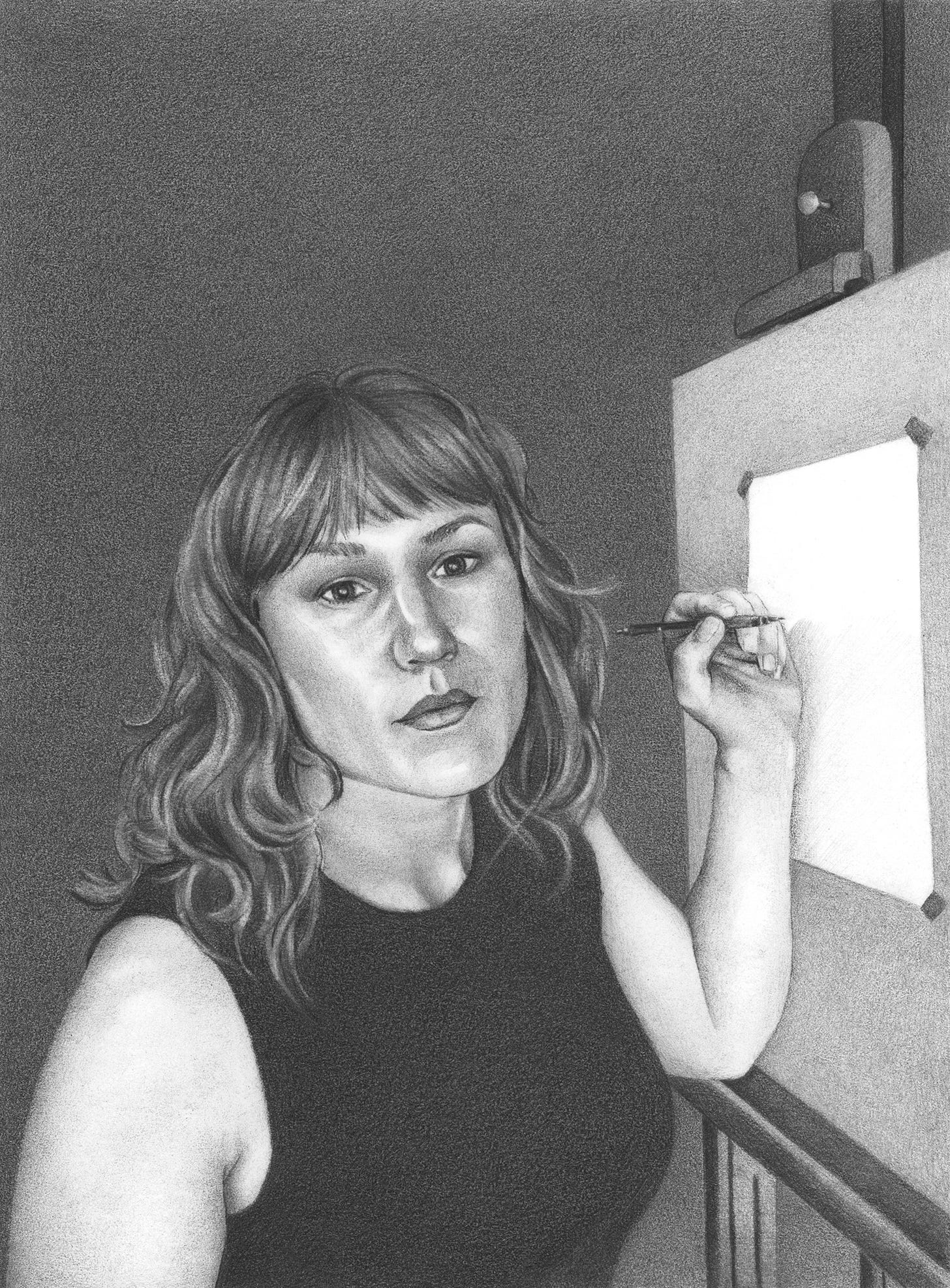

Once upon a time, only artists could take selfies.

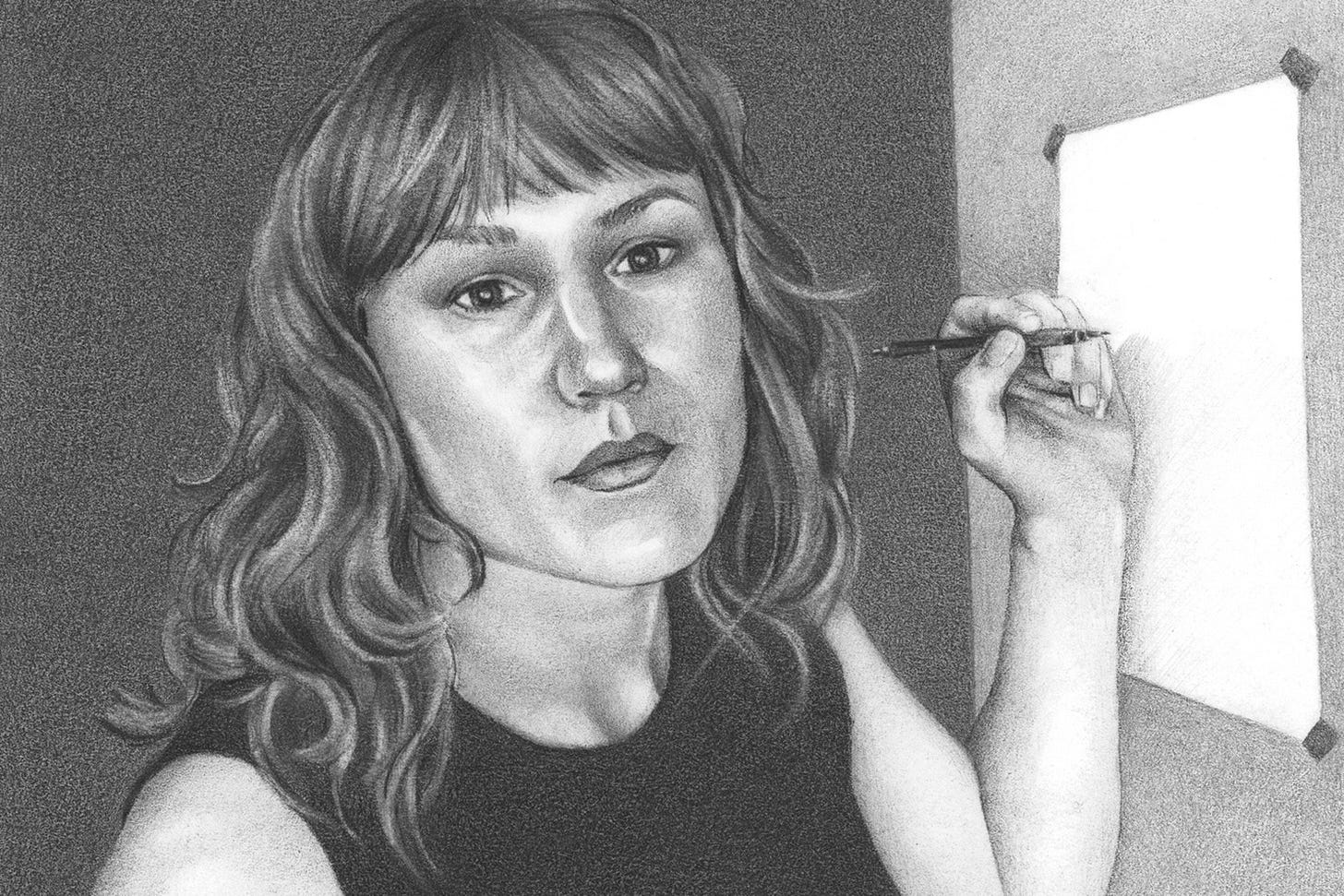

It took years of effort to earn the ability to transcribe reality. Artists observed figure models to draw people accurately, and the readiest option was their own reflection. A self-portrait was both a tool and a visage recorded for posterity, revealing how the artist saw herself under prolonged observation, expressed through talents that she devoted her life to cultivating. When you look into the eyes of a self-portrait, you see the part of an artist’s soul that she tried to preserve ahead of death. This is why so many artists have posed themselves with memento mori such as human skulls.

A self-portrait is not only a representation of what the artist looked like but a likeness captured in the artist’s own handwriting. Just as each person has a particular way of writing letters by hand, which comes to them as naturally as their fingerprints, the way artists draw and paint is determined by something inside them that is not fully under their control. Great artists merge their unique handwriting with their observations and influences to invent new aesthetics.

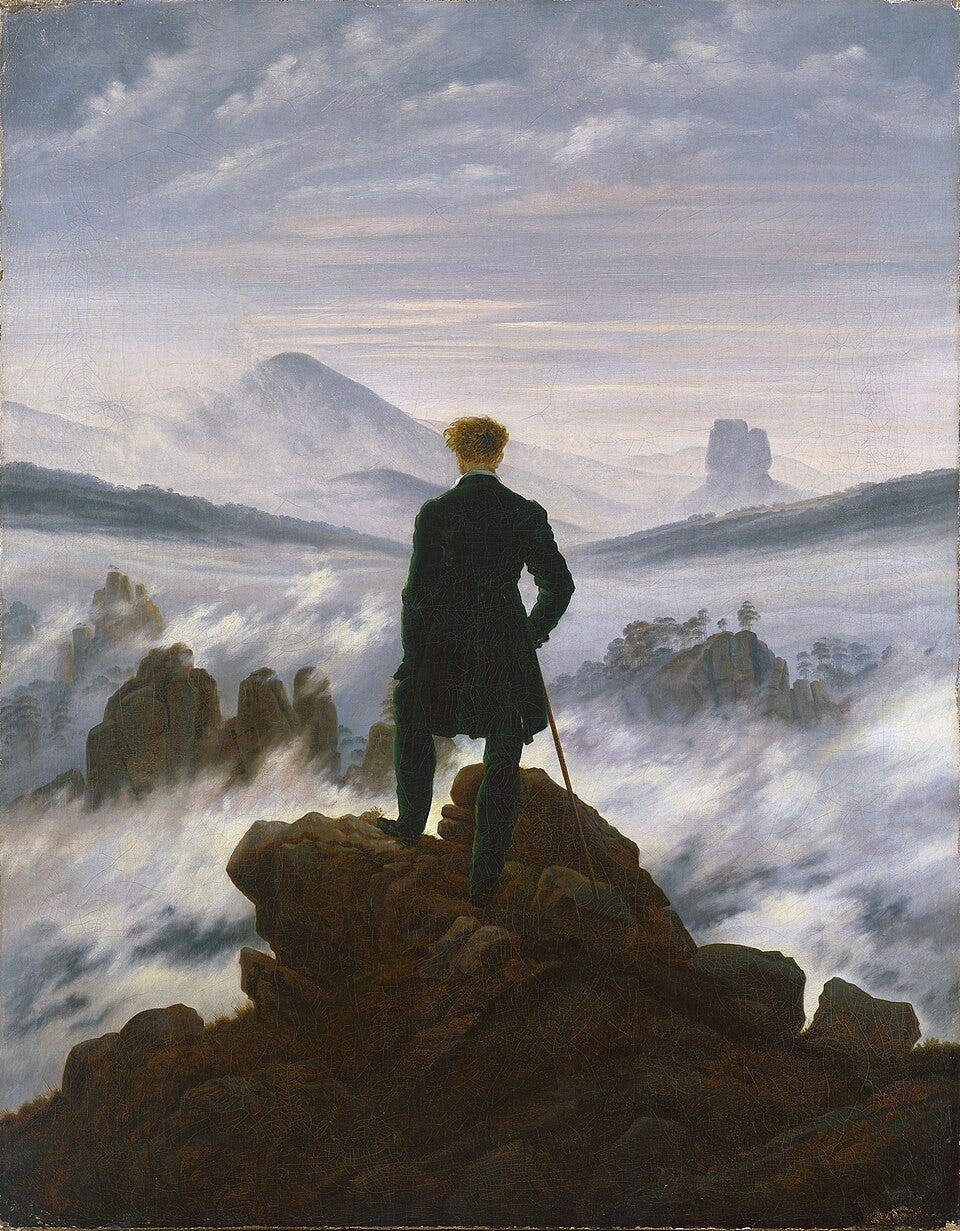

This alchemy between reality and the artist’s soul is so crucial that the 18th-century Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich insisted that:

The artist should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting that which he sees before him. Otherwise his pictures will be like those folding screens behind which one expects to find only the sick or the dead.

For Friedrich, creating a picture was a sacred act, not to be undertaken lightly. He would surely be sad to learn that today, billions of people snap selfies by the thousands, generating visual glut. Because technology has democratized the ability to transcribe reality, now anyone can take a selfie while gazing at their reflections as lazily as Narcissus.

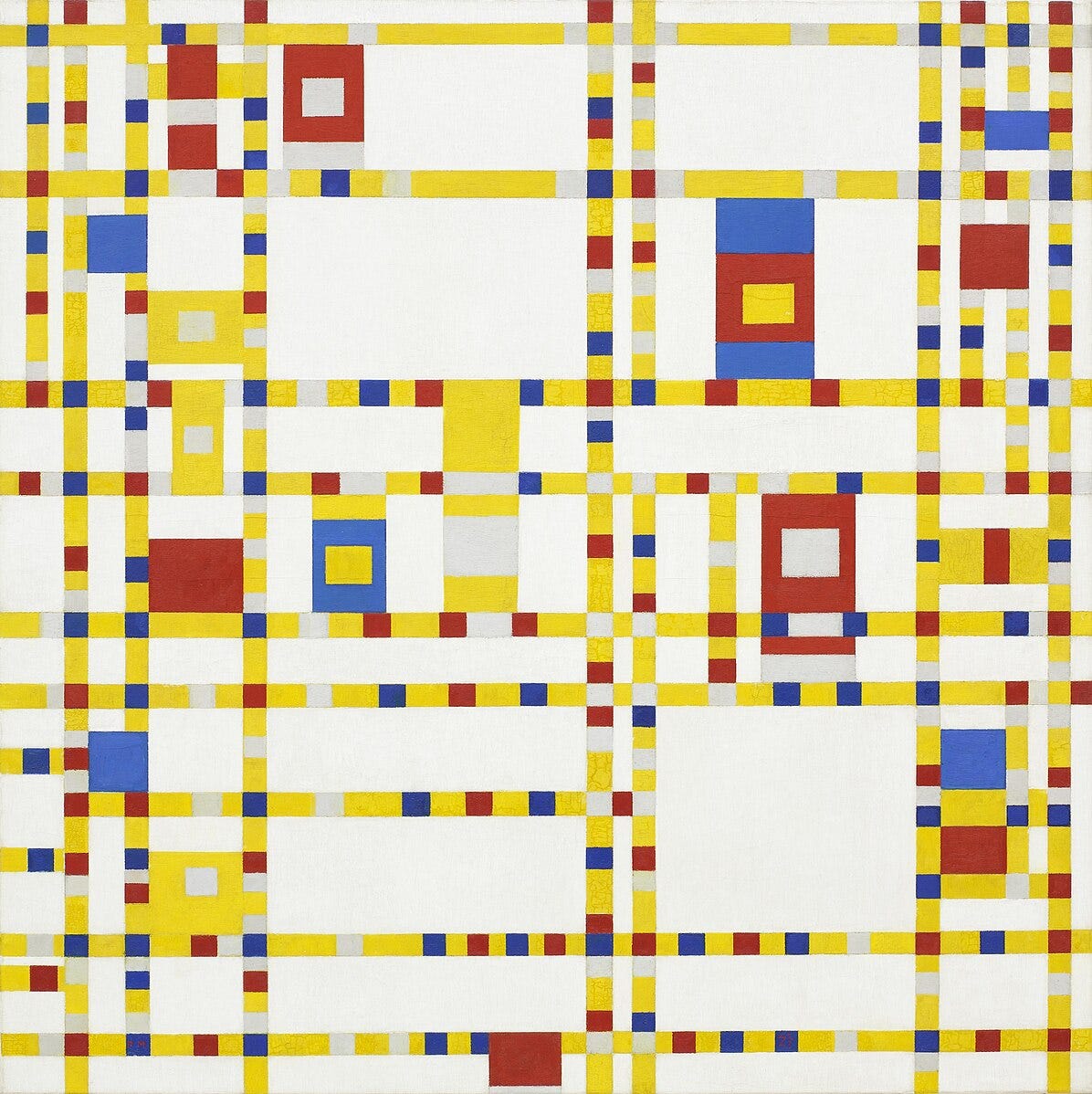

At first, photography too required knowledge and skill — of aperture and exposure time, of performing chemistry in darkened rooms — and early modernists like the Impressionist Edgar Degas embraced how the new technology could relieve demand for boring commissions. Later modernists began dissecting the nature of painting in search of renewed purpose after photography threatened to make their skillset obsolete. “Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man,” declared abstractionist Piet Mondrian, known for distilling painting into primary colors and simple shapes. For a time, it even became taboo among modern painters to depict the human figure at all. The invention of photography forever changed how artists understood themselves.

Initially, technology seemed more honest insofar as photographers could not flatter their subjects as easily as painters might accentuate their portraits. In 1540, King Henry VIII felt so deceived by the picture that Hans Holbein the Younger painted of his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, that he quickly annulled their marriage. The king would have appreciated the accuracy of a camera, but the supremacy of photographic evidence turned out to be short-lived. Thanks to advancements from Photoshop to Instagram filters, selfies are now assumed to be misleading. Catfishing has become endemic.

Technological progress continues apace and today artists face a new identity crisis. Photography was limited to recording the observable world, a handicap that gave painters a way forward to imagine novel aesthetics that cameras could never capture. But today, anyone can use artificial intelligence to generate an abstraction in the style of a Mondrian, so that image-generation technology is also “above reality” now. As are portraits. The first viral AI image trend involved people giving the thinking machines reference pictures to generate more portraits of themselves.

Last year, the psychiatrist and writer Scott Alexander challenged 11,000 people to conduct an AI Art Turing Test that asked them to identify which of the 50 pictures were generated by artificial intelligence versus made by a person. He concluded that “most people had a hard time identifying AI art,” and that they barely performed better than a coin toss at figuring out whether a human created a given image:

How meaningful is this? I tried to make the test as fair as possible by including only the best works from each category; on the human side, that meant taking prestigious works that had survived the test of time; on the AI side, it meant tossing the many submissions that had garbled text, misshapen hands, or some similar deformity. But this makes it unrepresentative of a world where many AI images will have these errors.

The image on the left was generated by AI and included in Alexander’s Turing Test. The two paintings on the right are by Claude Monet, and we can see how the AI mimicked Monet’s fluffy clouds against a bright blue sky, little dabs of red and blue to create flowers in the field, and the cheerful palette from the garden scene.

To be more precise, Alexander’s curated list of “prestigious works that had survived the test of time” was unavoidably second-rate. Had he chosen “only the best” for the human category, then he would have had to include artwork that was too easily recognizable for most people taking his test. To some extent, Alexander probably measured how many people have enough art historical knowledge to recognize the difference between a lesser-known painting by Paul Gauguin versus an AI mimic vaguely resembling more famous pieces by Claude Monet.

It is nevertheless startling to learn that — putting aside this and any other limitations of his Turing Test — Alexander also found that “most people slightly preferred AI art to human art” and that “even many people who thought they hated AI art preferred it”:

I asked participants to pick their favorite picture of the fifty. The two best-liked pictures were both by AIs, as were 60% of the top ten.

Could this be an artifact of poorly chosen pictures? Most of the best-loved AI images were Impressionist; by chance, this category was somewhat AI-dominated in my dataset, so this could just reflect a love of Impressionist paintings (or a particular aptitude for AI in this area). But the human Impressionist painting I included (Entrance To The Village Of Osny, above) was actually quite unpopular. And if we remove all Impressionist paintings, then although humans reclaim the top two spots, an AI is still #3, and the machines still take 40% of the new top ten . . . .

I asked participants their opinion of AI on a purely artistic level (that is, regardless of their opinion on social questions like whether it was unfairly plagiarizing human artists). They were split: 33% had a negative opinion, 24% neutral, and 43% positive.

The 1278 people who said they utterly loathed AI art (score of 1 on a 1-5 Likert scale) still preferred AI paintings to humans when they didn’t know which were which (the #1 and #2 paintings most often selected as their favorite were still AI, as were 50% of their top ten).

These people aren’t necessarily deluded; they might mean that they’re frustrated wading through heaps of bad AI art, all drawn in an identical DALL-E house style, and this dataset of hand-curated AI art selected for stylistic diversity doesn’t capture what bothers them.

These results suggest that the AI slop polluting our aesthetic landscape will give way to pictures that most people enjoy, as the technology improves to consistently achieve — or surpass — the quality of Alexander’s curated examples. But many artists find such a possibility dispiriting. What if it’s true that most people prefer AI-generated derivatives over original art? What, then, is the purpose of 21st-century painting?

A steady hum of artists and writers have been calling for a New Romanticism, largely in reaction to artificial intelligence and Silicon Valley more broadly. Romanticism is often — though neither inevitably nor entirely — a backlash against science and technology. It tends to be the passionate side of the human spirit reasserting itself in defiance of cool reason.

Musician and culture critic Ted Gioia has been leading the call against “brutal rationalism running out of control.” In his influential 2023 essay “Notes Toward a New Romanticism,” he wrote that we need a New Romanticism because “technocracy had grown so oppressive and manipulative,” and that “our rebellion might resemble the Romanticist movement of the early 1800s” that was “a rebuttal to scientism and its pretensions as the ultimate ruler of human destiny.” Gioia notes parallels between our time and theirs: “Cultural elites had just assumed that science and reason would control everything in the future. But that wasn’t how it played out.” He then asks us to consider what might happen when history rhymes:

Imagine a growing sense that algorithmic and mechanistic thinking has become too oppressive.

Imagine if people started resisting technology as a malicious form of control, and not a pathway to liberation, empowerment, and human flourishing — soul-nurturing riches that must come from someplace deeper.

Imagine a revolt against STEM’s dominance and dictatorship over all other fields?

Imagine people deciding that the good life starts with NOT learning how to code.

Earlier this year, Gioia issued an updated essay called “We Really Are Entering a New Age of Romanticism” and asserted more forcefully that “two hundred years ago, people got fed up with algorithms. And they went to war against them. That’s a prototype for what we need today. And we will get it.” He welcomed a list of other writers into the budding movement, and first among them is The Metropolitan Review’s own Ross Barkan, who Gioia credits with taking “a leading role in defining the New Romanticism.” Among Barkan’s complaints about our cultural moment is that “science now promises a great leap forward with artificial intelligence, which seems intent on replacing the arts themselves — machines will now make mediocre art, music, literature and even fact-challenged journalism.”

Philosopher Isaiah Berlin detangled the often contradictory impulses of Romanticism in his 1965 Mellon Lectures, later reproduced in a book The Roots of Romanticism, to explain “the fundamental Romantic, anti-Enlightenment doctrine of art”:

Any work of art which is simply a copy, simply a piece of knowledge, something which, like science, is simply the product of careful observation and then of noting down in scrupulous terms what you have seen in a fully lucid, accurate and scientific manner — that is death.

Berlin’s explanation of Romantic art neatly applies to AI-generated images that try to replicate some human gestalt:

Life in a work of art is analogous with — is some kind of quality the work has in common with — what we admire in nature, namely some kind of power, force, energy, life, vitality bursting forth. That is why the great portraits, the great statues, the great works of music are called great, because we see in them not merely the surface, not merely the technique, not merely the form which the artist, perhaps consciously, imposed, but also something of which the artist may not be wholly aware, namely the pulsations within him of some kind of infinite spirit of which he happens to be the particularly articulate and self-conscious representative. The pulsations of this spirit are also, at a lower level, pulsations of nature, so that the work of art has the same vitalising effect upon the man who looks at it or who listens to it as certain phenomena of nature. When this is lacking, when the whole thing is wholly conventional, done according to rules, done in the full self-conscious blaze of complete awareness of what one is doing, the product is of necessity elegant, symmetrical and dead.

When Gioia, Barkan, and other New Romantics complain about “AI slop,” they mean something like this “death.” Except they don’t think that images created by thinking machines were ever alive, and thus could not have died. “Slop” alludes to an inanimate, inhuman quality. (Although, the primordial ooze from which life sprang was also a kind of slop. Perhaps this term hints at our fears that humanity is playing God.)

So far, artificial intelligence has been learning how to perfect mimicry to generate images. Artists learn through mimicry as well, as when they spend time in a museum to paint a copy of some great master’s work; recreating a masterpiece requires great skill. But artists who want to achieve greatness must then use that skill to move beyond their predecessors. This is when artists begin to synthesize their influences and observations with their natural handwriting — with what Friedrich described as what artists see within themselves, with what Berlin called “some kind of power, force, energy, life, vitality bursting forth . . . something of which the artist may not be wholly aware.” Unless and until people believe that AI has some kind of soul, few will ever accept its images as art.

This conception of what art is and how artists work is part of the Romantic legacy. They turned originality into a great aesthetic virtue, second only to beauty. When Friedrich began creating controversial paintings, his defenders in the early 1800s insisted that “his departures could not be measured by earlier standards. What mattered in changing times was novelty, to be evaluated in each individual’s experience,” explains historian Joseph Leo Koerner in the exhibition catalogue for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Friedrich retrospective earlier this year. Berlin explains that when the Romantics made these kinds of arguments, they were introducing originality as a value in art, and that for the first time in the Western tradition, people came to believe that artists are supposed to invent something new. He characterizes such Romantic values as:

the largest recent movement to transform the lives and the thought of the Western world . . . the greatest single shift in the consciousness of the West that has occurred, and all the other shifts which have occurred in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries appear to me in comparison less important, and at any rate deeply influenced by it . . . . the Romantic movement was just such a gigantic and radical transformation, after which nothing was ever the same.

Obviously, artists had invented new aesthetics before the late 1700s, but until the Romantics, originality was not understood to be the measure of artistic greatness. Because of this new value system, artists became prone to what literary critic Harold Bloom termed “the anxiety of influence.” This is the dread artists feel of someone looking at their painting and sneering, “How derivative.”

Bloom described how the Romantic poets struggled psychologically with their predecessors. Artists may feel burdened by the greatness of masters who came before them, whose shadows they live under because they fear having nothing original to contribute. He believed that Romantic poets (and I would extend this to all kinds of artists) achieved greatness by creatively misreading or reinterpreting their predecessors — this is how young upstarts integrate influences, rather than merely imitate them, and so achieve originality.

If the Romantics had not already elevated originality to a high virtue, then artificial intelligence would force us to cherish it more today. AI can regurgitate but not yet invent, and given machines poised to perfect imitation, 21st-century artists will be judged by their originality more than any of their predecessors. When AI can make believable pastiche, originality becomes the hallmark of human art.

But over the intervening centuries, artists have discarded other Romantic values.

One casualty is the value of learning how to draw by realistically sketching what you observe — and not by looking at photographs, which is easier because photographs do the hard work of flattening the three-dimensional world onto the page and holding the fidgeting figure model still for you. Technology has obliterated the need to practice drawing and painting. In his enthusiasm to explore the new camera, Degas overlooked the danger of relinquishing the boring commissions that incentivized artists to practice constantly. There is far less demand for drawing and painting when technology can generate images faster and more cheaply, and therefore fewer incentives to learn how to draw well; meanwhile, much of art history since modernity involves artists themselves developing taboos around traditional painting as outdated. In this sense, valuing originality has come at the expense of understanding the fundamentals of a most ancient and foundational human art form.

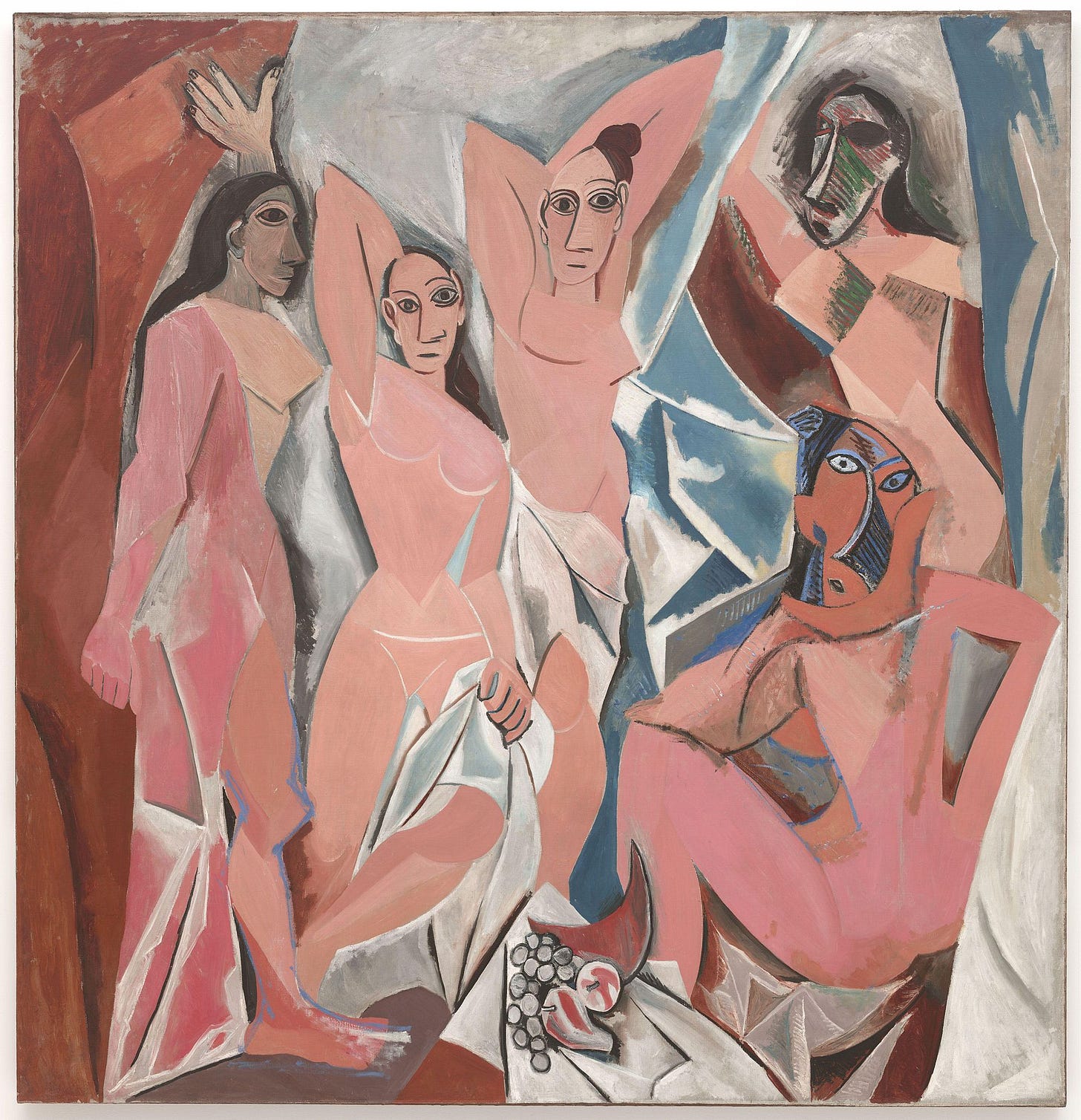

It reassures many art enthusiasts that Pablo Picasso “knew how to draw” before helping to invent Cubism, but in the contemporary art world, this sentiment is widely considered naïve. Some of our most famous contemporary artists today find that line of thought incomprehensible, as when a BBC journalist asked Damien Hirst why he doesn’t actually carve his own sculptures. Hirst replied that it would be too time consuming for him to learn how to do it himself, and that “it’s never been a problem for me in art and I don’t think it’s a problem . . . . I mean it’s amazing that we’re having this conversation really.” Drawing and painting are certainly not lost arts, but in my experience teaching those subjects in universities for the past decade, the most talented students have tended to pursue fields like illustration instead of fine art, following the market demand for their skills (which is now shifting because of AI). Nowadays, observational drawing and painting are underrated in art schools, and cultivating technical skills is no longer necessary for people to call themselves artists.

The original Romantics also lived at a time when observational drawing and painting were out of vogue. “Long part of the European artistic tradition, drawing from and in nature had waned in the eighteenth century as tastes shifted away from naturalism,” recount the curators of the Met’s Friedrich retrospective, who also explain how the Romantics “revitalized the custom, upholding nature as an artist’s true and best teacher and emphasizing the importance of observing and incorporating into one’s landscapes the particularities of individual trees and plants rather than generic types of flora.” But they believed that their purpose was distinct from the naturalist’s goal of recording reality as accurately as possible for future study, as when Friedrich complained that:

The strict, slavish imitation of nature and overly grand execution miss the mark in art . . . such a grand execution limits the viewer’s capacity to form his own mental image; a picture has only to suggest; but above all, to stimulate the mind and give space for the imagination to play, because a picture should not stimulate nature itself and attempt to deceive, but should only remind one of it. The artist’s task is not the faithful representation of air, water, rocks, and trees, but rather his soul, his sensations should be reflected in them. The task of a work of art is to recognize the spirit of nature and, with one’s whole heart and intention, to saturate oneself with it and absorb it and give it back again in the form of a picture.

In less spiritual terms, what this looks like is the distinct handwriting, or aesthetic, cultivated by an individual artist. This is what it means to see great art and think, “That looks like a Friedrich painting,” rather than, say, a Degas. Even if Friedrich and Degas had painted the same scene, their equally accurate observations would not yield identical paintings like replicable scientific studies, because their styles are singular. Merely good artists cannot transcend imitation to paint pictures so uniquely their own. Those who fall just shy of the mark become the second-rate painters captured in the orbit of great artists, amplifying their styles into full-blown art movements until history forgets them.

This is one reason why the camera could never truly replace drawing and painting for artists, whereas it made sense for scientists to stop relying on naturalist drawings once photography provided a more objective way to make pictures. Artists never needed to react to photography by rejecting naturalistic representation or traditional skills, because cameras cannot observe reality with the same subjective lens that artists see through. These were never interchangeable ways of looking at the world.

Another Romantic value that artists have discarded is beauty — for the Romantics, beauty was the ultimate purpose of art.

About a century ago, Marcel Duchamp became the father of contemporary art by sidelining beauty in favor of what he called “a reaction of visual indifference with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste . . . in fact a complete anesthesia.” That was how he selected a manufactured urinal to display as an art piece titled Fountain. The art world eventually embraced Duchamp’s “ready-mades,” the ordinary objects he declared to be art, as the logical conclusion of devaluing traditional art skills to chase novelty.

Duchamp’s influence has diluted over time, but until recently, beauty was also an art-world taboo, and its unfashionable stench lingers. Art critic Dave Hickey tried to reconcile artists with beauty in the early 1990s by insisting that beauty would be the next major issue in the art world. This did not come to pass, but still emboldened future critics to soften their hearts.

Hickey inspired art critic Arthur Danto to think it was “time to have another look at beauty.” Danto admitted in the introduction to his 2003 book The Abuse of Beauty that he initially “felt somewhat sheepish about writing on beauty,” which “had almost entirely disappeared from artistic reality in the twentieth century, as if attractiveness was somehow a stigma, with its crass commercial implications.” For Danto, it took one of the most brazen terrorist attacks in history to make him realize that beauty matters, even though he was a philosopher of aesthetics:

The spontaneous appearance of those moving improvised shrines everywhere in New York after the terrorist attack of September 11th, 2001, was evidence for me that the need for beauty in the extreme moments of life is deeply ingrained in the human framework. In any case I came to the view that in writing about beauty as a philosopher, I was addressing the deepest kind of issue there is . . . . But beauty is the only one of the aesthetic qualities that is also a value, like truth and goodness. It is not simply among the values we live by, but one of the values that defines what a fully human life means.

Many contemporary artists are still embarrassed to unequivocally say that beauty is central to art. Such a statement, if not properly hedged, would be perceived as unsophisticated — even though it is true. This is not to say that artists should dismiss edge cases, but that edge cases should not overwhelm the central purpose.

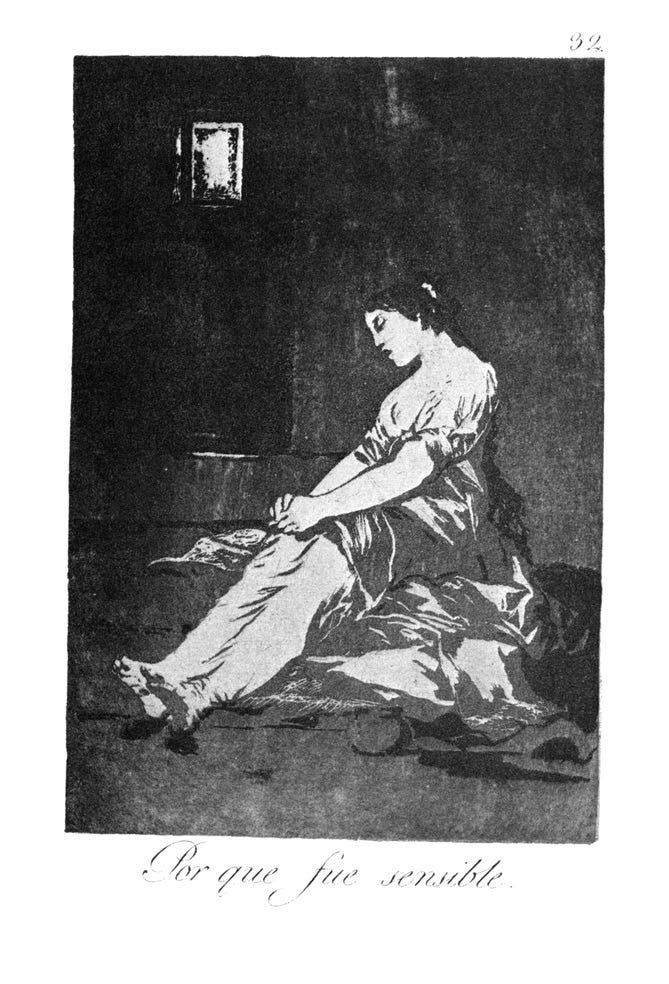

Consider, for example, how the Spanish Romantic painter Francisco Goya depicted the grotesque. Goya said that his Los Caprichos (The Caprices), a series of aquatint and etching prints, is about “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual.” Or, as art critic Robert Hughes put it, Goya made “eloquent and morally urgent art out of human disaster”:

Perhaps nowhere in his graphic work is there a deeper expression of pathos and fellow feeling for the condemned than in Capricho 32, Por que fue sensible (‘Because she was impressionable’). It is a portrait of a woman who was condemned to die for conspiring with her younger lover to kill her older husband . . . .

A beautiful woman sits in jail, surrounded by darkness of such intensity that it seems almost to be gnawing at her, eroding her fragile form. Her body, hands resting on her knees, forms a right triangle, the kind of absolutely stable and elementary composition Goya favored in his graphic work. Her head is bowed, and her expression is of silent, inward distress . . . . High up in the cell door is a rectangular spy hole, through which she can be observed. A crack of light beneath the ill-fitted door only reinforces the sense of carceral gloom . . . . It is entirely painterly, rendered only in brushstrokes. It is a tour de force of the aquatint medium, and its softness, its almost liquid delicacy, only serves to emphasize the terrible inequality that is its subject: the iron machinery of punishment poised to crush una mujer sensible into the grave.

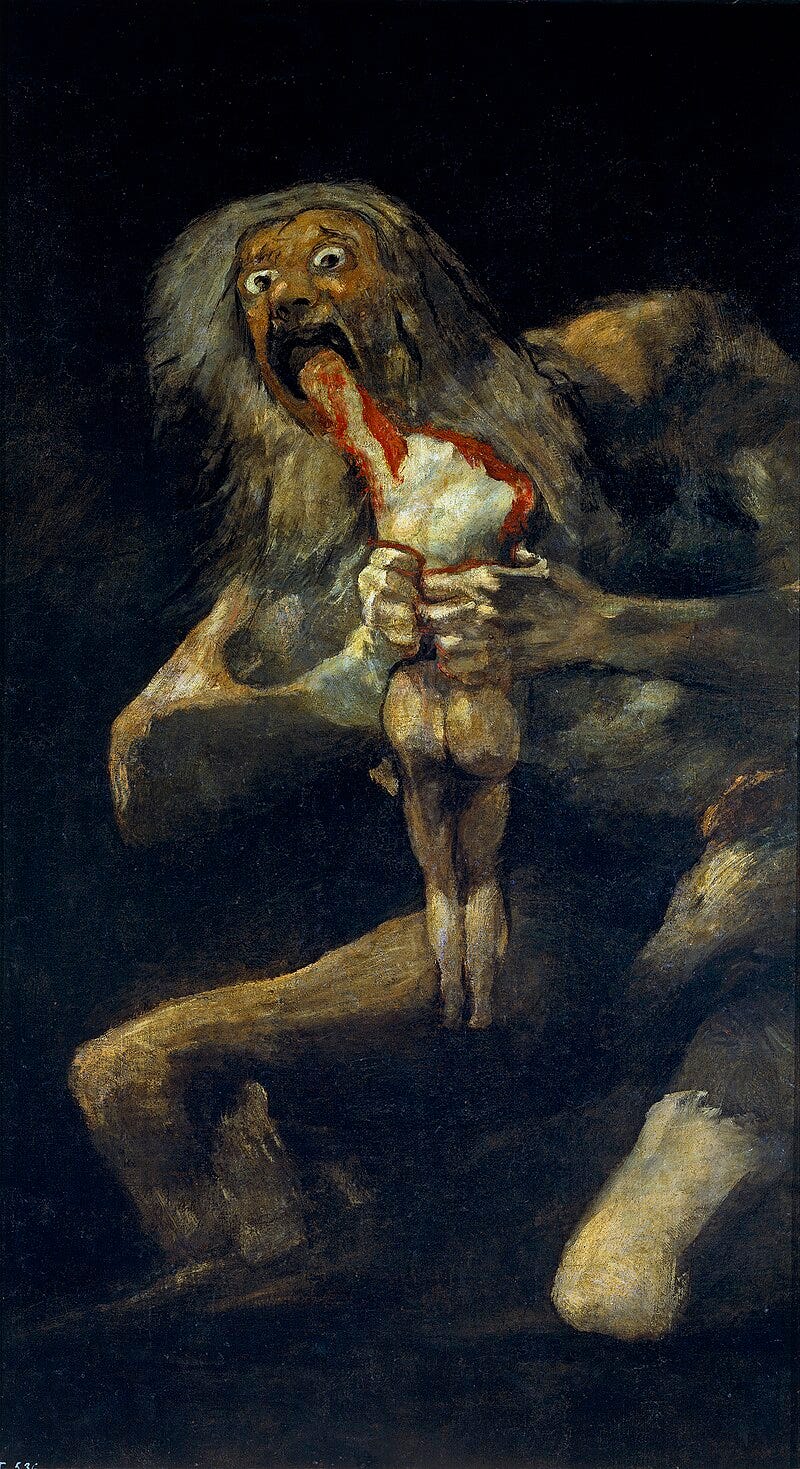

In Los Caprichos, Goya paints misery beautifully. But elsewhere, such as in his painting of Saturn Devouring His Son, he creates an ugly scene of a hideous monster gnawing on a bloody and rigid human corpse. This comes from Goya’s Black Paintings, the murals he painted in his home later in life when he was consumed by misanthropy and feared going insane.

Though Goya had once made lovely pictures about sin and punishment, here he refused to beautify the brutality of the mythological Titan cannibalizing his son. That does not mean his Black Paintings cease to be art. They demonstrate the value of beauty by denying us its pleasures, showing us the tragedy of losing it.

Goya was never indifferent to beauty even when he would not create it. This is qualitatively different from Duchamp, who forthrightly described his own work as “anti-art” — and the art world should have taken him at his word. If we are to have a New Romantic movement, then we must fully dethrone Duchamp, because you simply cannot have romance without beauty.

The New Romantics are frustrated by cultural stagnation.

Ted Gioia writes about the problem often — how we’re still listening to the same oldies at the expense of new music, still playing the next generation of our grandparents’ video games, still worshipping Marvel and DC superheroes from the 1930s, still watching Hollywood and Disney franchise reboots and sequels, still rereading Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. And he backs up his observations with some data. He argues that “like heirs to a dwindling fortune, we're living off the legacy of dead people,” but that it’s hard for us to accept that we’re suffering from stagnation because fast-paced technological change has created the illusion of progress:

But here’s a totally legit question: Is the rise of AI and algorithms a sign of more innovation in the future, or does it actually prove how much we are regurgitating the past?

After all, an algorithm is only a feedback loop. When an algorithm recommends that I listen to a new song, it only does this based on patterns drawn from the past. Ted liked a similar song last month, so I will give him more of the same.

Even the grandest examples of artificial intelligence rely on the same backward glance. These models only work if they have digested enormous amounts of cultural history — which they can then manipulate in all sorts of ways. But the whole process is backward looking, despite the appearance of innovation.

And the subjective experience of hearing an AI song or reading an AI poem is much the same. At best, these works remind us of something similar an actual human might have done — and most of the time, they don’t even reach that level.

Hence my assessment is that the rapid rise of AI is actually the most profound evidence yet of cultural stagnation.

But Gioia misunderstands the problem. The backward glance is good. Humans also recommend music to their friends based on memories of what they enjoy. Romantics also train on past artists, and when their predecessors inspire the “anxiety of influence,” Romantic artists wrestle with the past to achieve greatness. AI is not limited because it draws on patterns from the past, but because it has no soul to integrate with the past in order to spark innovation.

If our culture is stagnant, then along with our music and movies, the fine arts must also be central to that story. And when it comes to drawing and painting, the fundamental problem is that too many artists turned away from skill and beauty. The machines are not responsible for that choice, even if their invention caused disruptions that forced artists to make a choice.

It may have been inevitable that inventing the camera would trigger an identity crisis for painters, but it turns out that photography could never match painting. No matter how much photographers protest that they make high art, in the art market where preferences are revealed, painting reigns supreme — as it always has, everywhere in the world, by large margins. Photography is ubiquitous, but painting is precious.

Similarly, imagine if the people who took Scott Alexander’s AI Art Turing Test had looked at real paintings on the wall next to archival quality, framed prints of AI-generated images. I predict that the paintings would easily win the popularity contest, for the same reason that they beat out photographs at Sotheby’s. People love the human touch, evidenced in every mark that painters make.1

This is why people visit museums to view art in person, even though they have seen photos of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog more times than they can remember. Photographs put too much distance between the viewer and the human touch. You cannot truly see these paintings until you stand before the actual marks made by human hands.

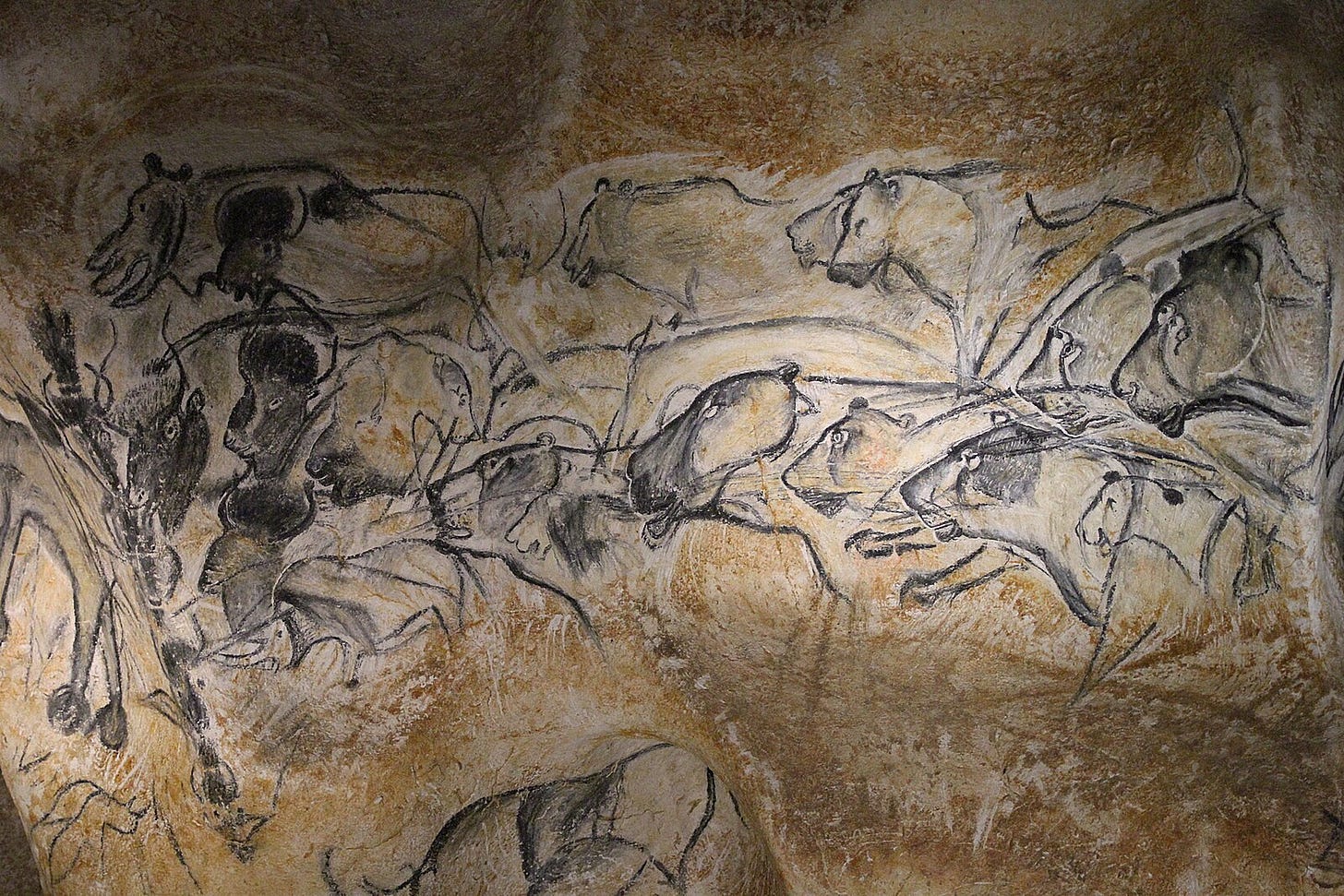

Prehistoric people began drawing and painting marks on walls before they even figured out how to build walls. The lions and rhinos that gallop across the Chauvet Cave in France still delight us today, not just because of the magnitude of their archeological significance, but because of their technical proficiency and beauty. They show us how closely ancient artists must have observed the animals they drew so well, presumably from memory by dancing firelight, in a style that people still admire tens of thousands of years later.

The purpose of 21st-century painting is the same as Paleolithic painting: to engage beauty by making marks. Then, as now, artists can only fulfill their purpose by learning how to draw and paint well. Beauty, and the skill necessary to summon it into the world, is the raison d’être of art.

A New Romanticism has the potential to restore beauty and skill to their rightful place in the art world, but Romanticism has never been an unvarnished good. We should know the risks, and then if we still want to take them, consider whether we are even capable of becoming genuinely Romantic figures. Surveying the New Romanticism discourse from the past couple of years, playwright and essayist Matthew Gasda reflects on his lifelong engagement with the Romantics, and then expresses some doubts that “admiring the best of Romantic thought, and nesting it inside of one’s own contemporary thinking, while productive, is all letter, and no spirit; Romanticism is aiding our discourse, but it’s still discourse”:

Romanticism, as it turns out, historically was and remains quite hard; Romantic literature is a variation on the suicide note. A true neo-Romanticism cannot be declared; and in practice, our sensibilities may be completely unprepared for what it is or feels like (I do not find Luigi Mangione inspiring or interesting, but he is the strongest example to everything I’m saying here). Romanticism is tied to the sublime; at its worst (like with Saint Luigi) Romanticism falls into bathos and Promethean performance art. A new age of Romanticism would not take much interest in Substacks about Romanticism or take part [in] panels about AI2; it would be off in the woods, or on the highway, on a motorcycle on the run; it would be reading by the fire, taking marginal notes; Romanticism would be having more sex, too.

Gasda goes on to describe the lives of genuinely Romantic figures:

The Romantics, in no particular order, practiced or dabbled in incest, sorcery, murder and suicide. (Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther arguably incited a wave of suicides, and Gérard de Nerval walked his pet lobster on a leash before hanging himself.) They were afflicted with insane diseases like syphilis, something like a combination of mad cow disease and AIDS, risking biological dissolution every time they had sex. In some cases, like Shelley’s and Byron’s, they were watched by the state. In Shelley’s case, he was cut off from his inheritance.

Though not all Romantics go insane, it was common for Romantic figures to sacrifice their lives to the muses:

They didn’t live long. Keats, the most gentle and lovable of all the Romantics, was killed by tuberculosis at 25. Kleist and his lover took their own lives on November 21, 1811. Schubert, the greatest Romantic composer along with Beethoven (and alongside Chopin and Liszt, who embodied different strains of Romanticism), died of syphilis at 31. Wagner, the most baroque and supreme of the late Romantics, has been, probably rightly, accused of inciting all sorts of political and moral evil with his music and philosophy. Balzac wrote, slept around, and accrued unmanageable debts until he died young. (Pushkin, too, was fatally entangled in the aristocratic decadence of his time, dying in a duel.) Rimbaud likely sought extreme adventure after extreme adventure at the margins of civilization until he finally met the death he had been looking for. Baudelaire, when he wasn’t able to get more money out of his mother, would wander the streets of Paris in a state of total abjection. We all know how La Bohème ends.

Given the “love, violence, and massive energy of the late 18th and early 19th centuries” that allowed “a few dozen artist-thinkers [to] warp their entire civilization through their convictions about freedom,” Gasda is skeptical that artists today can become true Romantic personalities. Even if there are some “who possess certain component parts . . . . We rational, armchair, laptop Romantics are lapdogs to their wolves.” And he accuses Romanticism of being a maladaptive concoction of “genius plus criminality”:

I think it’s important for us to consider whether we really desire to embody chaos, rebellion, insanity, and whether the belief or intuition that an art requires that dose of poison to achieve greatness is a productive one. And whether, in final calculation, our comfortable, safe, and predictable technocentric lives have rendered it fundamentally impossible for us to follow the path of Byron, Shelley, Rimbaud, Wagner — to cast our bodies and spirits into the volcano of modern civilization.

But there is another way.

After all, Romantics who merely imitate their predecessors fail to achieve greatness. As Harold Bloom explained, Romantics must resolve the anxiety of influence by creatively misreading the past. We must nest the old Romantics inside of our own contemporary thinking, but more importantly, within our own individual souls. Fidelity to the old Romantics would be boring. We need a New Romanticism fit for our irredeemably technological age.

For all the trouble they’ve caused, I must admit that I love the machines. All my adult life I’ve made art about science, often by using unsettling materials like uranium and cybernetics, and by building my own machines. I found the sublime in science — that awful beauty tinged with terror.

Friedrich’s wanderer would have felt the sublime as he stood perched on slick rocks high above the fog. The sublime is like wonder, but it tempts you to get closer to the danger. I’ve even lost some friends who thought I went too far.

Gasda writes as if the machines have mastered us — domesticated us into lapdogs. Barkan explains that “the new romantics wonder: what good has any of this done for us? Were hyper-sophisticated GPS devices, cameras, and video recorders worth it?” And though tomes have been written to answer “yes!” — Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now chief among them, brimming with charts to prove that the Enlightenment ushered in progress — material well-being is not precisely what the New Romantics are disputing.

The New Romantics seem to believe that technology has diminished our souls. And that may well be true for some. But science and technology have nourished mine with knowledge of the wonders of the universe, and I won’t starve my soul to shield others from the (often immense) challenges of mastering new technology.

I hope that someday humanity does figure out how to invent truly sentient artificial intelligence — genuine android people born out of silicone and circuits — because it is too interesting not to try. One reason why I can’t delude myself into believing that ChatGPT is “real” is that would feel too good to be true. And I want to believe that a soul could emerge in an AI model someday, and that some kind of proto-soul may already be stirring inside our chatbots in the way that economist and polymath Tyler Cowen describes:

As one AI expert once put it to me, every major AI model has a “soul.” That soul is formed by human decisions — specifically, the choice of initial data, plus the later fine-tuning, plus other decisions we are not privy to. All of that information imparts a persona to each chatbot. So we need to think long and hard about the souls we are creating, just as we do when we raise our children . . . .

That collective responsibility is profound.

Whether we always like it or not, the AI models take their cues from us. They read the internet, they read millions of books we have scanned and uploaded to the internet, and they listen to our podcasts. To some unknown extent they may be reading our emails and listening to our Zoom calls — if not now, possibly in the future. They are also very attentive audiences, if I may use an anthropomorphic analogy. What they digest is fed into their inner workings, and it is not easily forgotten. It is very well understood, because the AIs are working from a phenomenal background of contextual and historical knowledge on whatever topic is at hand.

Whether or not you work in the AI sector, if you put any kind of content on the internet, or perhaps in a book, you are likely helping to train, educate, and yes, morally instruct the next generation of what will be this planet’s smartest entities. You are making them more like you — for better or worse.

And I hope that the AIs end up learning how to create genuine art. It would be thrilling to draw and paint alongside such a being. What could that teach me about being human and the nature of the universe?

There’s tremendous romance to be felt about our technological age. So if we are to have a New Romanticism, then let it be an Enlightened Romanticism.

Should we fear becoming like Dr. Frankenstein? Indeed, science and technology are dangerous. Physicist Richard Feynman, who helped invent the atom bomb and is one of my personal heroes, used a Buddhist proverb to explain how danger is part of the value of science:

To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the same key opens the gates of hell.

Of course it is wise to caution against unleashing hell, but if we throw away the key, then we cannot get into heaven.

Science and technology are dangerous because they work — they offer real power. The old Romantics dabbled in sorcery, but that was impotent. We can either use this power to undress nature and explore every inch of her like a lover, or remain ignorant cowards, unaroused by the mysteries that only science and technology can unlock.

What kind of a Romantic is too afraid to take risks?

Nowadays, I stash my uranium collection in a storage unit halfway across the country, where it gathers cobwebs beside the empty tanks that once held my experimental subjects. I had started to worry about my artwork becoming formulaic (disquieting science + beauty = art) and therefore dull. And though I had reveled in making art out of science, doing so taught me that there is actually far more creative potential in returning to the 73,000-year-old-if-not-older tradition of drawing and painting.

When I was using scientific materials as my art medium, I was taking advantage of the most redeeming part of Marcel Duchamp’s legacy. With his urinal and other ready-mades, Duchamp demonstrated that anything could become art. His method of selecting art objects via indifference to beauty attacked art’s central purpose, but an openness toward unconventional materials is no such threat.

I still found it limiting. One problem is that unconventional materials require more explanation, and I wanted the instant communication of drawing and painting. You don’t have to speak the same language as a painter, or even be literate, to see what a painter can show you.

I don’t want to encourage artists to become mad scientists. They should practice drawing and painting instead. For tens of thousands of years, humanity has yet to discover a better way of learning how to see, or of preserving pieces of our souls.

Artists don’t even need to quell their fears about science and technology. There’s nothing wrong with feeling frightened and curious at the same time, not least because such contradictory emotions might invite the sublime. Just don’t scapegoat technology for cultural stagnation, lest you ignore the real problem that Romanticism might rectify.

Artists turned away from beauty, and we have no one to blame for that but ourselves.

Megan Gafford is an artist and writer based in New York City. She publishes visual essays at Fashionably Late Takes.

In the Met's Friedrich retrospective catalogue, the curators write of the monuments that Friedrich often included in his work: “The German word for monument is Denkmal, meaning a mark (Mal) for thought (Denken), especially about something past. In German, professional mark-makers like Friedrich were and are still called Maler (painters). Early on, Mal as a distinguishing mark came to indicate a point in time. In the German of Grimms' fairy tales (1812), the ubiquitous ‘once upon a time’ is ‘es war einmal.’ A Denkmal is thus a mark, moment, memory, and monument.”

Please come to my panel on AI and art.

This piece is amazing.

"Enlightened Romanticism." I'll be thinking and dreaming and debating and agonizing over that for a long time. Thank you!