Toward the end of this essay, I’m going to tell you about the time 30 years ago when Jim Harrison — the singular American poet and novelist — stole my date. This happened at a literary festival in Key West when I was 25 years old. Worse, I had flown there from East Lansing, Michigan, with nearly the sole purpose of meeting Harrison, whom I idolized.

Before I get to the story, let me discuss Todd Goddard’s sweeping biography, Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life. Harrison wasn’t a household name, but few writers have inspired a readership so passionate. Some of us have even made pilgrimages to the bars he loved — Dick’s Pour House, on Michigan’s Leelanau Peninsula; the Murray Hotel Bar, in Livingston, Montana; or the Night Before Lounge, a strip club in Lincoln, Nebraska. Years ago, I knew a successful New York-based author who discovered Harrison too late, just after his death in 2016, when for a couple of weeks fellow writers celebrated him with fond obituaries and gushing tributes. “I learned that everyone I know had apparently hung out with him at some point,” she wrote to me. “It was like how when David Carr died, I learned that he’d sent every journalist I know an encouraging email, except me.”

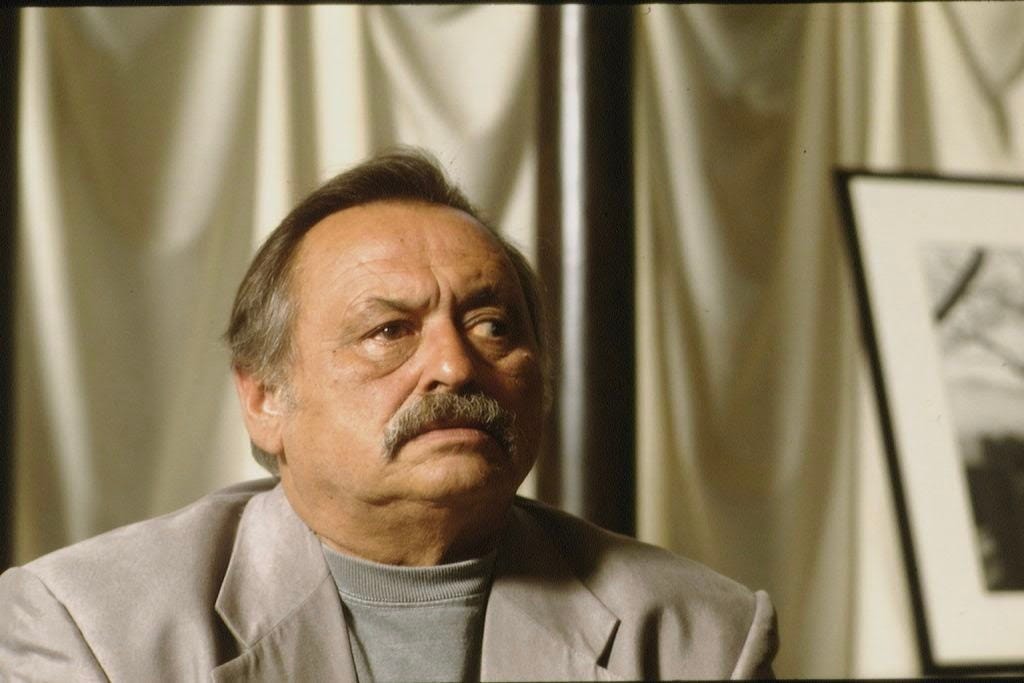

The easy way of describing Harrison is to say that he was driven by enormous appetites — for food, sex, booze, literature, and the natural world. The New York Times’ Dwight Garner, an admirer, called him “our poet laureate of lumbering desire.” It’s an apt characterization, though Goddard, an associate professor of literary studies at Utah Valley University, probes more deeply. His book draws from over 100 interviews, Harrison’s vast collection of personal papers, and intimate familiarity with his work. Goddard stresses Harrison’s accomplishments in poetry — the form he most cared about — and while his portrayal is admiring, it does not shirk from his flaws. The Harrison that emerges in Devouring Time is deeply sentimental and disarmingly cerebral, but never didactic. He grappled with metaphysical questions though he resisted abstractions; he found meaning in the dying of elk, winter rivers, and the savor of food.

Harrison was born in the northern Michigan town of Grayling in 1937, which back then was rooted in the timber economy. His Swedish ancestors were hardscrabble farmers, though his father worked for a New Deal agency. When Jim was seven years old, while “playing doctor” with a girl about that age, she thrust a shard of glass into his left eye, blinding him permanently. Later in his life, when posing for photographs, he often angled his ruined eye to the side, exposing its milky sclera.

Religion was strongly present in his family. Before proudly declaring as a teenager that he would be a poet, Harrison planned — amusingly, in retrospect — to become a fundamentalist preacher. He was precocious enough that at 18 he wrote a combative letter to John Ciardi, the Saturday Review’s poetry editor, expressing his distaste for so-called “academic poetry” — and Ciardi responded. Harrison remained a lifelong skeptic of MFA programs, which he compared to “Ford Motor Plants.” An aspiring poet would be better served, he later advised, working as a “truck driver, a proctologist, a stripper, a dishwasher, a furrier, a cowboy, an unlicensed plumber.”

At Michigan State, Harrison read widely and prodigiously, though rarely for his classes. He was a distracted and spotty student, dropping out and returning several times before finally earning two degrees there. As a young man he twice sojourned to New York City, styling himself as a post-Beat bohemian while occasionally sinking into depressions.

At 19, back in Michigan, Harrison fell in love with Linda King, whom he soon married in a shotgun wedding. To observers, their relationship has long seemed vexing: he wrote voluminously about nearly everything in his life — except her, which was as she preferred. Linda also did not share Jim’s wanderlust, so he almost always traveled alone. Goddard shows they deeply loved and depended on one another, and when times were lean — as they were until middle age — his inadequacy as a family provider weighed heavily upon him, a source of guilt and shame. This, however, can be hard to square with Harrison’s lifelong, assiduous wooing of women, about which he made little secret, and which some found distasteful. He was briefly linked with the starlet Jessica Lange and unsuccessfully pursued William Styron’s wife, Rose. He had numerous dalliances, sometimes with younger women who admired him, as well as some prostitutes.

Linda was at Jim’s side when his life’s greatest tragedy struck, in 1962. A drunk driver killed his father and sister, with whom he had deep, meaningful relationships. Goddard doesn’t mention it, but in his memoir, Harrison later listed among the errata of his life his decision to glance at a police photo of their brutally mangled bodies. Afterward, Harrison plunged even deeper into his writing. “You can see it in my first book, Plain Song,” he remarked. “If people die then you better get down to business.”

He moved to Boston, where he found an enthusiastic supporter in Denise Levertov, who was the poetry advisor for W. W. Norton. Though distrustful of academics, Harrison briefly taught in the mid- to late 1960s at Stony Brook University. His biggest “accomplishment” there was to help organize a major poetry conference in 1968, which brought scores of luminaries to campus, and was so libation-fueled, raucous, and fractious that at one point Allen Ginsberg fell to his knees, chanting Buddhist peace prayers.

Around this time, Harrison struck up, initially through correspondence, a lifelong, richly textured friendship with the ineffable Thomas McGuane, who had been one of his contemporaries at Michigan State, though they barely knew each other there. Goddard quotes liberally from their decades of letters, which “ranged from the performative — literary high-wire acts — to the confessional. . . . As the years went on,” Goddard notes, “they’d write to each other with the expectation that they were doing so for posterity.”

This was so even as Harrison’s early work met little success. From his 1973 poetry collection, Letters to Yesenin: “I don’t have any medals. I feel their lack / of weight upon my chest. Years ago I was ambitious / But now it is clear that nothing will happen.”

He was drinking and smoking too much — he would never stop — nor did he cease anguishing about his terrible health habits. Among the first of an improbable number of Harrison’s wealthy friends was the poet Dan Gerber, from the family that founded the iconic baby food brand; together they traveled widely, to England, Ireland, and the Soviet Union. Harrison is often celebrated for his epicurean appetites, but on some of these trips, he would overeat compulsively, darkly, to the point of sickness.

Harrison’s autobiographical first novel, Wolf: A False Memoir (1971) sold meagerly, though it garnered a couple of prominent and enthusiastic reviews. Its first sentence — a poetically inflected marvelment — runs two pages. A knock against Harrison, perhaps, is that throughout his career, his protagonists often seemed to mirror his own darkly comic voice and thinking. While driving across a flat, colorless stretch of Nevada, his character, Swanson, muses: “I see why they test atomic bombs in this state — if they didn’t, I would, only in more central locations.”

Harrison’s next novel, 1973’s A Good Day to Die, was better plotted but likewise sold poorly. Farmer (1976) was also unsuccessful, though both are excellent. Meanwhile, he struggled through northern Michigan’s gloomy winters while laboring in near obscurity. Also from Letters to Yesenin: “Suicide. Beauty takes my courage away / this cold autumn evening. My year-old daughter’s red robe / hangs from the doorknob shouting Stop.”

During this period, Harrison trekked regularly to Key West, where he roistered and fished with large-souled kindred spirits: McGuane, whose career was flourishing; Russell Chatham, a luminous painter of landscapes; Guy de la Valdène, a wealthy French sportsman; and the singer Jimmy Buffet, before he became famous. They collaborated on a small-budget cinéma vérité film, Tarpon, the appeal of which I’ve never quite understood — though Henry Begler approves1 — and some fishermen consider it a classic.

McGuane, flush with cash from his novels and screenplays, bought property just south of Livingston, Montana — he named it the Raw Deal Ranch — that became the locus of an exuberant, closely knit literary community. Harrison visited frequently and got his first true big break there through a friendship he formed with the actor Jack Nicholson, who effectively underwrote Harrison’s classic novella collection, Legends of the Fall (1979). Reviewing it in The Sunday Times of London, Bernard Levin famously called Harrison “a writer with immortality in him.” The book’s success “marked a tremendous change in Jim’s life,” Goddard says, “more tied to Hollywood, screenwriting, cocaine, movie stars, and especially money.” Legends also helped concretize Harrison’s reputation as a “macho” writer, a term he despised. “I write about the preoccupations I was born and raised with, fishing and hunting in the country,” he later groused. “Why is that macho?”

Harrison reveled in his newfound success, even as it sapped his time and energy. To recalibrate, he hired a trusted family friend as a personal assistant and formed an intense relationship with a New York City psychotherapist. But in a 1982 letter to McGuane, he shared a “brutal admission”: despite earning over a million dollars in the preceding four years — roughly $4 or $5 million today — he was broke. Given his druthers, he would have focused more on his poetry, but that’s not where the money was.

His next major achievement was his 1988 novel Dalva, which broke new ground by giving voice to a female protagonist, a Nebraska woman who searches for the child she gave up at birth. Both he and his editor, Seymore Lawrence, thought that book would be the one, and perhaps it should have been. But Harrison never did win a National Book Award or Pulitzer Prize; he was not even nominated. Some suspected that was because his interests in the American hinterland were too far from the gaze and tastes of the coastal literary establishment. Late in his career, however, Harrison became far more deeply revered in France than the United States. They called him “le grizzly du nord du Michigan” and “le Mozart des grandes plaines.” His public appearances were major events and people recognized him on Paris streets.

Harrison continued producing lyrical, meditative, and comical works — novels, novellas, poems, essays, and a couple of screenplays. He wrote prolifically and would never again be poor. He was tickled when the New Yorker published his novella “The Woman Lit by Fireflies,” another impressive work. One of his memorable essays, “A Really Big Lunch,” recounted an eleven hour, 37-course meal he took in Burgundy, France, where the menu was drawn from recipes in 17th and 18th-century cookbooks and “likely cost as much as a new Volvo station wagon.” Many readers also loved his Brown Dog chronicles, about an unlucky, hard-drinking, half-Ojibwe trickster who drifts across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Some sensed that his later fiction did not measure up to Legends and Dalva, and that is probably true — but his poetry rarely wavered. As he aged, he wrote especially well about illness and mortality. From his 2015 collection, Dead Man’s Float:

My work piles up,

I falter with disease.

Time rushes toward me —

it has no brakes. Still,

the radishes are good this year.

Run them through butter,

add a little salt.

Harrison entered an early physical decline, and Goddard’s acute descriptions of his ailments — diabetes, gout, kidney stones, back pain, blood pressure spikes, respiratory, prostate, and bowel problems, shakiness, and various convalescences — should give pause to anyone prone to romanticizing his unruly modes of excess. He hated having to curtail his traveling and to give up his remote northern Michigan cabin: “I’d rather sell my kidneys to a republican,” he wrote to a friend. He even had to fight the State of Arizona to keep his driver’s license. There was at least some mordant humor, Goddard notes, in the image of Harrison, “a lifelong intellectual and writer,” straining with shaky hands and poor eyesight to pass the written portion of his state’s driving exam.

Harrison died in 2016, in the most fitting way — hunkered at his desk, writing a poem. “Had Jim written the secret number of birds he had counted in a lifetime on a slip of paper as he had once promised in the poem ‘Counting Birds?’” Goddard muses. “If so, he did not get to pass it to his wife and daughters from his deathbed, as he once imagined.”

About that trip to Key West: I had become intoxicated by Harrison’s work in college. My enthusiasm was intense. At the time, I was working on a master’s degree in history but thought I might pursue a Ph.D. in English, and I secured a travel grant to attend a multi-day festival on American Writers and the Natural World. Harrison would be featured there, along with my second-favorite writer, McGuane, and others I admired. But the clear goal was to meet Jim.

And I did get to briefly introduce myself to him. He signed a book and posed for a picture. But the idea that he would take any special interest in me — because I was a fan, and I too was from Michigan, and knew its northern woods — well, that was of course a juvenile fantasy.

Otherwise, the conference was fine. Most of its attendees were much older than me; they seemed dilettantish and well-heeled. I purposefully dressed down in a flannel shirt. There was, however, an attractive woman there, about my age, who was also a grad student, from someplace in Florida. We hit it off a bit. The first day, we talked. The second night we kissed on a bench. For the third night (I confess) I hoped maybe we’d have sex. We’d made dinner plans, but at a late-afternoon reception she told me she wouldn’t be able to make it: Jim Harrison had invited her to a group dinner. Ugh.

We adjusted our plans and agreed to see each other afterward for late-night drinks. We set a time to meet at Sloppy Joe’s, a bar that Hemingway famously frequented, but had since devolved into a garish tourist trap. I showed up and waited for her. I continued waiting, longer than I should have. (This was before cell phones.) Eventually, two of her English professors walked in, and my heart sank when I overheard one murmur to the other: “Oh no, he’s still here.” They approached me gingerly, knowing I’d been waiting for [name forgotten]. “I’m sorry,” one said. “I don’t think she’s going to make it.” They’d just seen her boarding Jimmy Buffet’s yacht — with Jim Harrison. He was 58 then, but seemed older, and used a cane — maybe to manage his gout or possibly just to offload his massive weight. Regardless, I’d not stood a chance. About a month later, the woman I’d fancied sent me a letter apologizing; nothing sexual had happened with Jim, she stressed.

I met Jim again in 2002 at a reading outside Boston. This time, we actually got to chat a bit. I mentioned someone we knew in common and asked for his opinion of Richard Yates. Eventually, I brought up that we’d briefly met six years prior at that Key West conference, and that while he surely hadn’t known it — and of course there were obviously no hard feelings — he had poached my date.

He lit up with a giant grin. He remembered that night well, he said, not least because he’d ended up stuck with the entire $3,000 tab from the dinner party. The truly amazing thing, though, was that he’d seen her again, just the night before, on his book tour. “She came to my party at Elaine’s!” he boasted. I asked if she was still very pretty. He responded, still radiant, with a wisecrack that made me chuckle — but that was also so outrageously lewd and disarmingly specific — that I will never repeat it in print. Except to say that I am glad that Jim Harrison did not live to see the #MeToo movement.

John McMillian teaches recent American history at Georgia State University, in Atlanta. He is the author of Smoking Typewriters and Beatles Vs. Stones. His new Substack is Mick’s Opinions.

This was lovely. I wasn't aware of Todd Goddard's new book. Thanks for that. I love Jim Harrison's work beyond measure, though I struggled with how much I loved it due to the misogyny that only increased with time. He was good friends with friends of mine, so I was lucky enough to have shared two meals with him. He was brilliant and bawdy and kind and tender and funny and, of course, a mesmerizing storyteller who commanded the table. Here, too, he said some things I will never share in print.

Thank you! Harrison is my favorite though I didn't discover him until right before he died. His words soothe and transport me. He also can be quite funny especially in the Brown Dog books. Wish I could have met himfor a drink or ten. Can't wait to read this book.