When David Lynch died, the internet filled with quotes from him. I usually cringe at these sudden and predictable proliferations of soundbites that become nearly meaningless in their ubiquity. The point in moments like this is to show that you are the kind of person who posts a David Lynch quote, the quote itself is secondary at best, you might as well just post a square with the words “David Lynch Quote.” This time though, there was one quote that made its way through to me, that stuck in my brain, looping. “Ideas are like fish,” David Lynch supposedly said. “If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you've got to go deeper. Down deep, the fish are more powerful and more pure. They're huge and abstract. And they're beautiful.”

I wrote the quote down. I repeated it to myself. I repeated it to my students. I kept repeating it because Lynch is talking about risk and lately I have been obsessed with the interplay of art and risk. I don’t know exactly when the seed of this obsession began, but I can point to two things I read that brought it into full bloom: Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature and Shane Denson’s “The New Seriality.” I read Sinykin’s book with the same dread and thrill as a true crime narrative — aha, so this is what killed idiosyncratic literature! And then I read Denson’s article in a similar but even more impulsive way — this is what is continuing to kill idiosyncratic lit, the crime is happening right now as I read.

Sinykin’s Big Fiction tracks the conglomeration of publishing and how editors went from talking jazz and pouring drinks with their writers in the 1950s to poring over profit-and-loss statements and how these shifts were caused by the buying up of independent, often family-owned, publishing houses by companies like RCA and other large corporations, and how the consolidation of these multinational corporations led to a risk-averse model with no room for low-demand commodities. What this means practically is both a refusal to publish books that do not mimic other recent, financially-successful books and the death of the long-range model wherein an editor like Albert Erskine could continue to publish an author like Cormac McCarthy whose pre-Border Trilogy novels never sold more than 2,500 copies each.

In “The New Seriality,” Shane Denson pushes the reader to think about the ways in which algorithmic, predictive media lead to the “serialization of life itself, which renders past, present, and future behavior into repeatable and predictable quantities. Accordingly, the ultimate (as-yet-unrealized) purpose of predictive algorithms is to predict, which is to say shape, who we will become.” Do you want to post a David Lynch quote because you have always loved this David Lynch quote or do you want to post a David Lynch quote because you saw fifty people post David Lynch quotes today and suddenly you realize that you do in fact love this quote and are the kind of person who posts David Lynch quotes, even if yesterday you were not a David Lynch quote posting person?

I began to be obsessed with risk and art because I felt like it had become so difficult to find new (recently published) books that were utterly unique; in recent years, fewer publications review books at all, and the ones that do tend to prioritize the same few, already well-publicized titles. The books in the windows of stores I pass are all some version of the same trend, and social media repeats the same names on a shrill loop. I am of course far from the only person to note this tendency and even my complaining about a lack of uniqueness is in no way unique. In 2022, there arose a spate of thought pieces on cultural boredom. Literary critic Christian Lorentzen posted to Substack that “boredom is pervasive,” then went on to lay the fault at the feet of the “cult of marketing,” which has led to a scenario where:

. . .books and movies shilled by corporations have started to become indistinguishable from their own marketing campaigns. Indeed, it’s been argued that pop songs are merely advertisements for tours now that albums are dead, movies are advertisements for their sequels, and books are applications for their authors’ teaching gigs or else merely bloated streaming-TV treatments.

Three months later, in the New York Times, Michelle Goldberg complained not only about her own boredom but also about Lorentzen’s boredom and his supposedly misdirected conclusion about the source of his boredom. Goldberg didn’t like that Lorentzen blamed marketing, complaining that the “risk aversion of cultural conglomerates can’t explain why there’s not more interesting indie stuff bubbling up.” I wonder how Goldberg thinks that anything “bubbles up” without marketing of some sort, but the point of her op-ed was really to hail W. David Marx’s Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change. Marx himself responded to Goldberg (and the 1,200 or so comments on her piece) by underscoring the role of the internet in Goldberg’s boredom:

In the last few decades, mass culture successfully neutralized the constant aesthetic challenge of indie avant-garde experimentation, either by delegitimizing it as pretentious or quickly absorbing and defusing its innovations. The internet meanwhile promised to be weirder, more niche, and more interesting, and yet the zeitgeist is anchored to mega-moments, rehashed reboots, and lowest common denominator viral content . . . . [The] explanation for this is that (1) status value was always key to the appeal of avant-garde and indie culture, and (2) the internet conspires against providing such content with status value. In the ensuing vacuum, the mass media and elite consumers spend their energy engaging with mass culture, which is more likely than niche content to be conventional.

Goldberg laments the lack of the “truly cool” by complaining about music in coffee shops but what she is, almost inadvertently, pointing out is a trend that threatens not just to deny us groovy café vibes but to remake the ways in which we receive and metabolize all new art. I try not to be too alarmist, but I think this is a time for alarm.

It is not unique to blame the internet. Many others have written about the impacts of the digital age including Lorentzen who, in his 2019 article for Harper’s, outlined the shift in his role as a literary critic, saying that he was “put on notice” that he was now a simple link in capitalist food chain, a purveyor of products to fill the feeds of those who “believe in the algorithm” and to comfort them by demonstrating that “everyone else is watching, reading, listening to the same things.” Blaming the internet for artistic uniformity is nothing new but in reading Big Fiction and “The New Seriality,” I began to conceptualize the overlap between conglomeration and algorithmicity as the perfect storm in the true crime death of the availability of idiosyncratic literature. I am not complaining that distinctive books do not exist, but rather that we are rapidly losing the means of accessing them. After reading Sinykin and Denson, I began to frame the ways in which the Big Five publish (and Big Media publicize) novels as a form of serialized and predictive media, wherein individual novels written by different authors are part of a serialized whole aimed at unimagined communities of actants assembled for the purposes of profit, or as Sinykin says, “conglomerate era fiction displays properties attributable not to any one individual but to the conglomerate superorganism.” If we agree with Lorentzen that the relationship between art and the algorithm is one in which viewers are encouraged to consume “the same things,” then we might also understand current novels to be both prequels and sequels to other novels written by other writers, episodes in a serialized stream. These novels are linked into a series through the proliferation of blurbs which tie one author and book to another and another, through comparison titles, and through publicity lists which have overtaken the review.

Comparison or “comp” titles are not an entirely new phenomenon, but their importance has risen meteorically as conglomeration and serialization have become the new norms. Comp titles are now often printed right on the cover of new books along with the phrase “for readers of . . . ” and their importance throughout the acquisition process is unparalleled, or as one Big Five editor recently told researcher Laura McGrath, “Comps are king in this business.” McGrath has done extensive research on the impacts of comp titles and the ways in which they reinforce whiteness and other conservative trends in publishing. In her 2021 article for American Literary History, she quoted an agent as saying:

If [editors] can’t find a book that [a potential acquisition] is like [i.e. a comp title] — if it’s really, really original — then they can’t buy it. Which is crazy! Because the whole point is that people should want to read something that they’ve never read before! That’s what publishers were asking for a couple years ago. They said, “We want something new and fresh and different!” So I would say, “Here! Read this! Here you go! On a platter! New, fresh, different!” And they’d say, “But we can’t find the comps!”

McGrath demonstrates that while comp titles have always served a supposedly instructive role (“this book is like that book”), in recent years they “have become prescriptive (‘this book should be like that book’) and restrictive (‘ . . . or we can’t publish it’).” Blurbs are also not new, having existed at least since 1855 when Walt Whitman took a line from a letter that Emerson wrote to him and emblazoned it on his book, but the prominence of blurbs has mushroomed in the conglomerate years. In the Philippe Besson novel that I just plucked randomly from my shelf, there are nine entire pages worth of blurbs linking the text to a series of other recent books and movies.

The list (think “50 Queer Books to Celebrate Pride With” or “25 Bright Books to Warm Your Winter Days”) is perhaps the most obvious form of serialization. Book reviews by their very nature tend to treat books as singular whereas lists treat them as serialized episodes. The death of the book review has been brought on by many factors, including the death of newspapers and the death of our attention span, but one of the main reasons that Big Five publishers cannot be bothered to care about the lack of reviews is the fact that the review does not help to serialize or algorithmize books unless the review itself goes viral. Only one newspaper maintains a stand-alone book review (the New York Times) and there are fewer than a dozen staff critic positions across the whole nation. In December 2022, Bookforum was purchased by the publishing conglomerate Penske Media Corporation and was shut down one week later. The publication was subsequently purchased by The Nation and revived in 2023, but the swift financial ruthlessness of Penske’s CEO, Jay Penske, demonstrates the new conglomerate mode. While some, like Sam Eichner in the Columbia Journalism Review, have pointed to a what they call a “recent rise in books coverage,” this rise is a rise in clickable, shareable, reproducible, algorithm-driven content (lists, rankings, Instagram posts, TikTok videos) aimed at garnering lucrative web traffic, one click leading to another and another. From Penske’s point of view, in the time it would take you to read and think through a single complex portrayal of a work of literature in Bookforum, you could have clicked on a nearly endless stream of “book coverage” links, thereby generating more and more capital for him.

Lists and blurbs and comp titles are all marketing techniques of course — they are not themselves the art — but they impact the style and content of the books because as Lorentzen says, books have become “indistinguishable from their own marketing campaigns.” Lorentzen states this without taking it much further. I agree with him, but I want to unpack why and how this is true. Authors now cannot get publishing contracts if their novels do not resemble another recently published (and financially successful) novel, thereby generating a good sales prediction. Or, as Sinykin says “the published [conglomerate] author also channels the norms of a cultural system, its sense of literary value. She forges a commodity that will appear attractive to scouts, agents, editors, marketers, publicists, sales staff, booksellers, critics, and readers.” Publishers have always wanted their books to sell, but the transfer of independent houses into the hands of multinational corporations with shareholders intent on exponential growth has led to “market segmentation and sales prioritization,” which has in turn led to a focus on more bestsellers written by a smaller group of brand-name authors. The sales prioritization was aided by the advent of Amazon sales numbers and BookScan (founded in 2001 following the success of Nielsen SoundScan which tracked point of sale figures for music). In the click of a button, a conglomerate publisher can see sales numbers on past titles by any particular author and just as importantly, on comp titles. It is the norm now at larger publishing houses to generate sales predictions (by way of comp titles) before even scheduling an initial acquisition meeting, and if the sales are not predicted to hit a high enough number, the editor is not allowed to schedule the acquisition meeting, no matter how much they love and believe in the manuscript. The style and taste of a supposedly “individual” publishing house is created by BookScan, a tool used by every single large publishing house when they produce sales predictions based on comp titles. The oddest aspect of this model is the fact that “comping” is such a, dare I say, fictional method of prediction. Editors must compare new manuscripts to financially successful books published within the past three to five years and this model heavily encourages them to make comparisons to the same books over and over again, with the titles that compare most favorably to these select few, previously-published titles becoming the ones that make it to the bookstores. No wonder everything looks and sounds the same — I could barely write that sentence without making it unreadably repetitive.

This push towards the predictive model leads publishers not only to publish similar books but to publish books more quickly as serialization speeds up. We might take the scandal of the “plagiarizing novelist” Jumi Bello as a prime example of conglomerate serialized authorship gone (slightly and very informatively) wrong.

In the spring of 2021, Bello, then a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, went under contract with Riverhead Books for her debut novel, The Leaving. Editor Calvert Morgan wrote to Bello, praising her novel but also saying that he had read it “in a mad rush” and stating that “we both want to get this done in short order.” This was less than a year after the murder of George Floyd and Riverhead was clearly in a hurry to publish this novel — written by a Nigerian-American and focusing on the experience of a “Black woman in a world where racism is real.” The publication date was set less than a year away and Bello was given two months to complete and edit the novel (in the past, literary novels have traditionally taken two to four years to move from submission to pub date). Six months before the pub date, after the novel was already appearing on “most anticipated” lists, Bello approached Morgan and said that she wanted to see if there was still time to review some sections of the book. She told Morgan that she was afraid that some parts of her book were “too close to a James Baldwin story.” When Morgan looked at passages of Bello’s manuscript beside Baldwin’s story, he saw that Bello had used Baldwin’s exact words. It soon became apparent that more than thirty percent of Bello’s book was plagiarized. The book was never published and the story of the plagiarizing novelist who also plagiarized significant portions of her confessional LitHub essay on plagiarizing ripped through the literary world. I am less interested in the salacious details of that situation than I am in the ways the scenario fits into the serialized and predictive publishing model — a model that does not take into consideration the needs or desires of either the authors or editors. So many aspects of the Bello-Morgan saga perfectly illustrate the ways in which the serialized, predictive publishing model is meant to work. From the publisher’s perspective, the only failure was Bello’s revelation. Viewed from a different perspective, she is a canary in the coalmine, swept into, then chewed up and spit out by the algorithmized tides of corporate media machines.

In the serialized, predictive model, publishers seek books that are, as Denson says, “both novel and predictable” and which speak to topics that are on the horizon of our expectations. They want to acquire books that are similar, predictable, comparable, and they must rush these books out into the world before the accidental serialities that they are a part of shift, before attention deviates from George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, and they must rush them out in order to have them remain connected to the other novels with which they are compared. In one “most anticipated” list, Bello’s novel appeared just below the novel Black Cake, their cover designs extraordinarily similar, and the descriptions could almost be interchangeable (debut — debut, “estranged” — “tendency to push away,” “grapple with mysterious past” — “revisit a troubled past,” “spans countries” — “spanned the globe,” “puzzling inheritance” — “generational trauma”). I do not point out these similarities to disparage The Leaving or Black Cake, but rather to illuminate the fact that publishers no longer treat novels seriously and respectfully, as singular works of artistic merit. They eagerly take on books that closely resemble one another and publicize them in a serialized manner; this in turn leads to the writing of books that resemble one another and the rapid and serialized consumption of such books (The Leaving was promoted as a “critical read this year,” as if its importance had an expiration date, and this very description of course showcases the publisher’s fear that the book’s importance may indeed fade while also making clear their reasoning for publishing the book at all). The predictive serialization of literature is bad for writers in general, but it is particularly bad for writers of color who are still enormously underrepresented in mainstream publishing. As Laura McGrath so astutely points out in her 2019 LARB exposé “Comping White,” the publishing industry “was discriminatory long before such data-driven acquisitions were a common practice. But comps codify the discrimination that writers of color have long faced, perpetuating institutional racism through prescription: this should be like that — if you want to be published — if you want to be well paid.”

The main difficulty that publishers have in fitting into the new serialized media model is the fact that it takes time to make a physical book. I would guess that the eleven months in which Bello’s novel was meant to appear on bookshelves would be the bare minimum possible. In order to remain a part of the predictive cycle, publishers must hurry and in hurrying they cannot give writers time. Once consumers become comfortable with AI-written books this aspect will no longer be a problem, but as long as most novels are still written by humans, it will remain a sticking point. Bello in part blamed the publishing schedule for her plagiarism; she felt rushed to finish the book and, at least partially as a result of this rush, she turned to a method that interestingly and uncannily mirrors the methods of AI-writing systems. Bello has said that in order to write a scene about, say, pregnancy, she surrounds herself with different texts that touch on pregnancy, copies sentences from them, and then intends to later “change the language.” According to an Air Mail profile, “Right alongside her work in progress, Bello will have open a Word document filled with all of her favorite passages from a single author. ‘I’ll read them over and over again in hopes that I will feel that creative force,’ she says.” AI models similarly utilize a vast database of text (including thousands of novels) to find, repurpose, and collage together relevant words and phrases. In addition to the ways in which the sped-up publishing schedule may have impacted Bello’s process, other aspects of the conglomerate media world may have consciously or unconsciously shaped her as well. In 2024, Yasmin Nair wrote for Current Affairs about the deadened uniformity of recent book coverage in the New York Times Book Review. With fewer and fewer publications reviewing new novels, authors are more apt to look to the Book Review and, Nair argues, its “emphasis on the Big Five publishers and book sales has meant that writers likely feel compelled to write towards what they imagine a Book Review critic might want to see,” leading us to “a world where unspoken traditions about how to read and whom to read and why have taken hold and authors are compelled to write in ways that conform to gendered and racialized expectations.”

Publishers are not yet as much a part of the predictive media world as, say, Netflix is, but they are reaching in that direction. You can even see it as early as the 1990s in the trend that Sinykin writes about of literary writers turning to genre models, one of the most obvious cases being Cormac McCarthy’s turn toward genre techniques in The Border Trilogy and all of his subsequent books, a turn which allowed his books to be seen as part of larger serialized and highly marketable trends (Westerns and Post-Apocalypticism, for example). This turn not only required more recognizable plots but also necessitated a drastic shift in McCarthy’s prose, a shift into something far less singular (one of my all-time favorite writer anecdotes is the story about how William Gay stood in line at a book signing, nearly in tears, begging McCarthy to tell him why All The Pretty Horses had none of the wild biblical diction of his previous books). In the new seriality, the author becomes simultaneously more and less important; they are more important as a tool for promoting their particular “episode” through their personal identity, but they are less important as the creator of that episode because the episode must not deviate too much from what has come before and will be coming very soon. Singularity cannot be serialized.

What can be endlessly serialized are Romance novels. Romance publishers have long known the importance of suppressing singularity and have been promoting multi-author seriality through cover designs and formulas since long before the algorithm ever existed (think nursing romances, Amish romances, frontier romances, gothic romances — all of these types of novels are sought out not for who wrote them or how the prose sounds but for the tropes that they will predictably employ). As editor Ann Kjellberg says, romance . . .

readers needn’t look for individual books or authors so much as easily identified types of stories, what the industry called “category” marketing (as opposed to the inefficient “single title” marketing of trade publishing). Observers have noted that this micro-segmentation of romance has also contributed to its amenability to Tiktok, which directs users minutely in the direction of their known enthusiasms.

So-called “literary publishers” are somewhat new to the idea of “category marketing toward known enthusiasms,” but they are picking up on it quickly and enthusiastically through the use of genre, quickly produced “topical” books (a critical read this year), and “re-imaginings” like Barbara Kingsolver’s hit Demon Copperhead (taking the “comp” to the level of rewrite). The key linkage in these literary serialities is predictability: when “literary” books heavily utilize genre tropes, spin off of topical moments or borrow plots of canonical works, the marketing and publicity teams have a path already mapped for them.

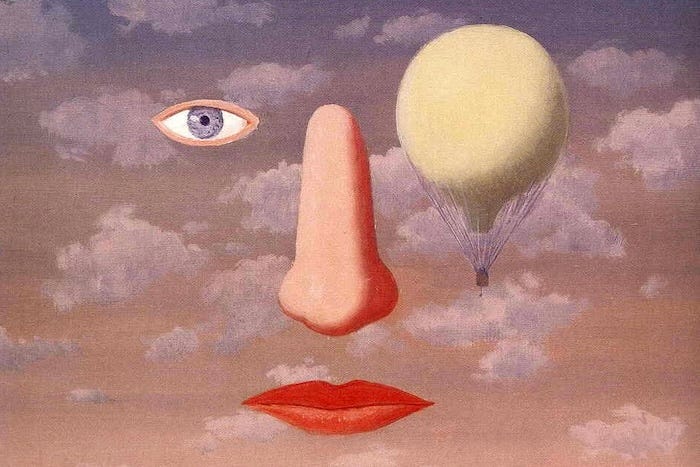

The term “”literary” has been debated for years. It is not a very useful term at all and I for one would like to see it replaced, although I’m not sure what to replace it with (maybe we should just borrow from Lynch and call them “down deep books”). For me, the word literary is only useful as a way to denote books that are meant to be read on their own, with focus and deliberateness, where the experience of each word and sentence is foregrounded. I don’t want “genre” books to not exist, I just don’t think that anyone benefits from a blurring of the difference between “genre” and “Down Deep.” We do not need to talk about these kinds of books hierarchically, but it is ridiculous and harmful to everyone if we pretend that there are no differences between highly-serialized books and books intended to be interacted with outside of the seriality. I purposely say “intended to be interacted with outside of the seriality” and not “created outside of the seriality” because it is no longer possible to entirely create something outside of algorithmized seriality. As Denson says, our very lives are serialized. There do, however, still exist works of music, art, and books that are intended to be interacted with individually and in a foregrounded way. The problem is, how do we find them? With so much of our lives being lived online and so much of book promotion happening on social media, this is becoming a real problem.

The books that “do well” online are conglomerate, serialized books. For a book to “do well” online, it must be able to be reduced to a quickly consumable and comparable description (“for readers of . . . ”) because, as we all know well, social media is not built for nuance. This inevitably leads to what Sven Birkerts calls the loss of “the very paradigm of depth.” The things that make books interesting to me (sentence rhythm for example) are often the aspects that make works non-serializable (i.e., unpublishable at least by the big publishers) and these are also the aspects that are least often mentioned on social media or in reviews. The few book reviews that do still make their way out into the world almost never mention formal aspects of a book, but simply summarize the plot and the themes and connect these aspects to other books with similar plots and themes in order to make the reviews themselves more serializable. The text, or at least the way in which the text was written, is beside the point; the point is the larger themes and the ways that they fit into the ongoing algorithmic series. Novels do not need to be written in an interesting way, they need only to be described and marketed in a way that fits the algorithm (in fact if they are written in an interesting way, this may make them more difficult to sum up quickly and therefore less marketable). In 2018, critic Wesley Morris described this trend by saying that, in the past:

We were students of the work — its devices, strategies, vision, achievements and problems. We were little deconstructionists. The makers’ personal story? Their intent? Those didn’t matter. The text was all. What has transpired in the past decade — the shifts in power, politics, media, higher education and economics; the calls for reckonings and representation of all sorts — might have transported us to an uneasy new place: post-text.

If, in 2018, we might have been in a post-text place, then in 2025 we unquestionably are in a post-text era. The text has no place in a serialized reality.

Hardly anyone talks about Pandora anymore (when you google “Pandora” the predicted search is “does Pandora still exist?”), but when thinking about seriality it is worth taking a minute to note the differences between the ways in which Pandora and Spotify suggest songs. Pandora works by analyzing songs based on hundreds of musical attributes like tempo, melody, instrumentation, and lyrical style, creating something like a “DNA” for each song, allowing it to recommend similar songs based on your thumbs-up or thumbs-down feedback. Spotify’s algorithm uses machine learning to analyze listening habits of other listeners “like you” so that the popularity of a song will make it more likely to be recommended to you, not necessarily because it has a similar instrumentation style to songs you like, but because it is frequently listened to by people who also listen to other songs that you listen to. Writing in Harper’s recently, Liz Pelly drilled into the phenomenon of Spotify’s “ghost artists,” where real live artists are paid a flat fee to record simple, genre-specific tracks which are then released, by the companies that commissioned the songs, under fake artist names and fed into an internal Spotify program called “Perfect Fit Content” (PFC) where Spotify employees fill playlists with this cheap content which rises in “popularity” with each listen. These “ghost” songs are, as the name Perfect Fit Content suggests, the perfection of the serialized form, each one just slightly different from the last without being singular enough to draw any particular attention to itself, thus perpetuating the serialization on and on and on in the background. These are the romance novels of the music world, remarkably unremarkable and thus utterly consumable and serializable, built for the algorithm. Pelly writes that this system “puts forth an image of a future in which — as streaming services push music further into the background, and normalize anonymous, low-cost playlist filler — the relationship between listener and artist might be severed completely.”

The book business has for many years been impacted by, and largely ended up following, music business trends, from the RCA takeover of Random House in 1965 to the shift toward the singular popstar (a focus on a smaller roster of individually chart-topping artists rather than a larger and more varied roster of artists landing at various levels on the charts but balancing each other out) and, as I mentioned above, the rise of Nielsen SoundScan followed ten years later by BookScan. With this history in mind, I think we would all be naïve not to admit that ghost books are coming, and surely will be written by AI soon, though perhaps with a little human touch so that they can be promoted using human identities. I think that AI books and “ghost books” are inevitable, and while we cannot stop them from coming, we can differentiate them from the Down Deep. This is why I think that we must stop blurring the lines between highly-serialized books and books intended to be interacted with outside of the seriality. This kind of blurring only benefits the conglomerate publishers and does not benefit readers. As an example of this blurring, if you google the phrase “literary fiction published recently,” one of the very top hits is Coco Mellors’ Cleopatra and Frankenstein. A quick peek at the first two pages reveals the novel to be very carefully following classic romance genre tropes. If you google “tropes for the opening of a romance novel,” you find the most commonly used trope is “forced proximity” defined as “characters unexpectedly thrown together in a situation where they must be close to each other.” Mellors’ characters are momentarily trapped together in a freight elevator in Tribeca.

This is a romance novel and there is no shame in that, but there is a real shame and a danger in believing it to be “literature,” i.e., something that demands to be foregrounded and interpreted in a non-serialized way. The danger is that people will think they are having experiences (the experience of reading literature for example) that they are not actually having. In the world we live in right now, we don’t listen to muzak and believe ourselves to be having the same kind of experience we might have while listening to, say, a Black Sabbath album. But in the near future, if (or should I say when), as Pelly says, music gets pushed further into the background and there is a normalization of anonymous, low-cost playlist filler, then very soon someone might mistake the two experiences. The same thing is true for books.

In his manifesto Reality Hunger, David Shields writes, “Capitalism implies and induces insecurity, which is constantly being exploited, of course, by all sorts of people selling things. Therapy lit, victim lit, faux-helpful talk shows, self-help books: all of these prey on our essential insecurity. The great book, though — Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, say — takes us down into the deepest levels of human insecurity, and there we find that we all dwell.” I share this quote both because it seems to point in the same direction as David Lynch, down into the deep, and also because the story of the publication of The Book of Disquiet is maybe one of the best examples of the antithesis of the serialized, conglomerate publishing model. Corporate publishing isn’t going anywhere anytime soon but it is not the only option. We need to celebrate those publishers whose methods might be more apt to lead to something like The Book of Disquiet, a text that began its life as some 350 fragments shoved into an envelope inside a trunk stuffed with 25,000 written scraps left by Fernando Pessoa at the time of his death. The book was first painstakingly assembled and released in 1982 by Edições Ática, then translated and released in Italian in 1986 by Feltrinelli Editore, and then in English in 1991 by both Carcanet Press and Serpent’s Tail. The publication history of The Book of Disquiet serves as a sort of abridged who’s who of avant-garde publishers — Feltrinelli was famous for having arranged for the manuscript of Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago to be smuggled out of the Soviet Union (after reading the original Russian version, Feltrinelli’s advisor told him that to not publish it would “constitute a crime against culture”). Feltrinelli also published Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer even after it was banned in Italy. Carcanet was a small poetry press originally organized by students at Oxford and Cambridge and Serpent’s Tail, founded with “a mission to introduce British readers to risk-taking world literature” has published such iconoclastic idols as Cookie Mueller and Hervé Guibert. These publishers, and others like them, put time and resources into the dissemination of truly singular works of literature instead of comps of comps of comps; they know, as Walter Benjamin demonstrated in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” that imitations of works of art not only lack the singular aura of the original but in turn depreciate the original itself, substituting “a plurality of copies for a unique existence.” It is for this reason that we need to seek out, support, and praise those publishers who, in these highly serialized times full of crimes against culture, take risks on originality1. They may not be what is popping up repeatedly in the frenzy of our social media feeds but for that very reason they are sure to be worth the extra effort it takes to find them.

Mesha Maren is the author of the novels Sugar Run, Perpetual West, and Shae.

A (far from complete) list of such publishers:

Hub City Press

Deep Vellum

Two Dollar Radio

Clash Books

Dzanc Books

Nightboat Books

Soft Skull Press

Ugly Duckling Presse

Dorothy Project

Semiotext(e)

Melville House Books

Archipelago Books

New Directions Publishing

McSweeney’s Internet Tendency

Autumn House Press

Rescue Press

Tell me all of the small presses that I neglected to put on my (far from complete) list! For my list I stuck to American presses because I am criticizing American (Conglomerate) Publishing- from what I can tell the publishing ecosystems outside the US are much healthier (a good mix of big and small and far less conglomeration)

Fantastic analysis. Thank you.

I've been thinking and talking with others about the supposed necessity of publishers (grounded in my experience as a former publisher of a small, risk-oriented press). Increasingly it seems to me artists will be better served by trusting their instincts and publishing their own work going forward. Rather than ask for permission, the internet and the advancement of production processes allows artists to ask for support. Crowdfunding, handmade titles, Patreon, or hell, putting a project on credit... All allow the artist to control as much of the status, quality, and presentation of the art object as possible.

The small publishers doing good work are wonderful, but the notion of "house style", or the belief that a label can accurately indicate the quality of its offerings, seems to have been pretty cooked by the serialized and a la carte nature of algorithms. In other words, it's harder to get folks to trust that a group has done and will keep doing good work—a skepticism that is both heartening (because it promotes assessing things individually and resisting groupthink) and scary (because it distrusts the socially-essential fact that groups of people are capable of good work as such, thereby further atomizing us).

I think artists should more often take and use the means of production and communication. The importance of the publisher will ideally lessen with time. Hopefully more syndicalist, union-esque artists' collectives will pop up—pledging and practicing mutual support and aesthetic diversity. We'll see.